The Golden Age of Islam & World History

The Islamic Golden Age, from 800 to 1200 CE, the time of the three great Islamic philosopher-logicians, al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, was one of the most important periods of human history, like the Tang Dynasty of China (618 – 907) just before it and the Italian Renaissance (1400 – 1600) just after it. Sumerian, Babylonian, Syrian, Persian, Indian, Greek, Roman and Chinese culture was gathered and developed in Islamic lands, first Arabia, soon after Persia, and then a vast empire that stretched from Spain to China, the largest in history.

The Islamic Golden Age, from 800 to 1200 CE, the time of the three great Islamic philosopher-logicians, al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, was one of the most important periods of human history, like the Tang Dynasty of China (618 – 907) just before it and the Italian Renaissance (1400 – 1600) just after it. Sumerian, Babylonian, Syrian, Persian, Indian, Greek, Roman and Chinese culture was gathered and developed in Islamic lands, first Arabia, soon after Persia, and then a vast empire that stretched from Spain to China, the largest in history.

When we study the history of thought, it is wise to remember that we have not been doing history for very long. Writing is only several thousand years old, the type-based printing press, one of the most important devices Muslims passed from China to Europe, is only a thousand years old, and popular literacy has been very rare until recently in the wealthiest parts of our shared world.

When we study the history of thought, it is wise to remember that we have not been doing history for very long. Writing is only several thousand years old, the type-based printing press, one of the most important devices Muslims passed from China to Europe, is only a thousand years old, and popular literacy has been very rare until recently in the wealthiest parts of our shared world.

Muslims have a great appreciation for the golden age of Islam, but we who are American or European do not. I myself didn’t until I was in graduate school, studying the history of philosophy and religion. Unfortunately, if we are not aware of what Islam gave the world, we do not understand European or modern history much, because what ancient India, Greece and China gave our modern world passed through Islamic hands across their vast caliphates and then through caravans reached beyond.

Muslims have a great appreciation for the golden age of Islam, but we who are American or European do not. I myself didn’t until I was in graduate school, studying the history of philosophy and religion. Unfortunately, if we are not aware of what Islam gave the world, we do not understand European or modern history much, because what ancient India, Greece and China gave our modern world passed through Islamic hands across their vast caliphates and then through caravans reached beyond.

Without paper, press, compass, gunpowder, algebra, calculated insurance rates and countless other devices and ideas, the Italian Renaissance, European colonialism and our modern post-colonial would not have happened as it did. The Western Europeans, a.k.a. the West, my Celtic and Germanic ancestors, did not have wealthy cities in the time of ancient Athens, but like the Arabs, ignored as barbarians until their age by the powers that bordered them, they conquered many who considered themselves civilization itself.

Without paper, press, compass, gunpowder, algebra, calculated insurance rates and countless other devices and ideas, the Italian Renaissance, European colonialism and our modern post-colonial would not have happened as it did. The Western Europeans, a.k.a. the West, my Celtic and Germanic ancestors, did not have wealthy cities in the time of ancient Athens, but like the Arabs, ignored as barbarians until their age by the powers that bordered them, they conquered many who considered themselves civilization itself.

Christian Europeans have, for centuries after getting Greek texts from Muslims, focused on connections between ancient Greece and Western Europe, ignoring connections between ancient Babylon, Egypt, Persia and Greece, and connections between India, China, Islam and Europe, which is a very partial and narrow view of our common world history. When we do study Islam, Europeans, such as myself, focus on Plato, Aristotle and their impact on Islamic thought, the impact of this on Christian European Neo-Platonists, or Islam in the modern world after 1700, the time when Europeans had the upper hand in money and power, which was not so before the 1600s, the time that Newton used algebra to deduce cosmic laws of physics.

Christian Europeans have, for centuries after getting Greek texts from Muslims, focused on connections between ancient Greece and Western Europe, ignoring connections between ancient Babylon, Egypt, Persia and Greece, and connections between India, China, Islam and Europe, which is a very partial and narrow view of our common world history. When we do study Islam, Europeans, such as myself, focus on Plato, Aristotle and their impact on Islamic thought, the impact of this on Christian European Neo-Platonists, or Islam in the modern world after 1700, the time when Europeans had the upper hand in money and power, which was not so before the 1600s, the time that Newton used algebra to deduce cosmic laws of physics.

Philosophy departments rarely offer courses on Islamic philosophy or logic, and few departments of any subject study Islamic literature, philosophy, or science. In a recent book (2005) on al-Farabi, one of the most important Aristotelian logicians for later European logic, the author begins by stating we have many, many excellent studies of the ancient Greeks, and medieval Europeans, but “our” (European) understanding of Farabi and the history of Islamic logic is “in its infancy.” Meanwhile, Farabi’s face is on the Khazakstani dollar. As with Indian and Chinese thought, Islamic thought is covered, if at all, as Religious Studies, not as philosophy or the history of science.

Philosophy departments rarely offer courses on Islamic philosophy or logic, and few departments of any subject study Islamic literature, philosophy, or science. In a recent book (2005) on al-Farabi, one of the most important Aristotelian logicians for later European logic, the author begins by stating we have many, many excellent studies of the ancient Greeks, and medieval Europeans, but “our” (European) understanding of Farabi and the history of Islamic logic is “in its infancy.” Meanwhile, Farabi’s face is on the Khazakstani dollar. As with Indian and Chinese thought, Islamic thought is covered, if at all, as Religious Studies, not as philosophy or the history of science.

I enjoy teaching Indian, Greek and Chinese comparative philosophy, and if you study these subjects, you will eventually find that understanding Islamic philosophy is very helpful, but quite hard to do, because there has been a greater appreciation of Indian and Chinese culture and thought in European scholarship and counter-cultural movements that involve the Bay Area, San Francisco and Berkeley. Some have said this could be an example of the grandfather effect: If everyone in the family gives heck to the next one over, then the grandfather gives heck to the father, the father gives heck to the son, and so the grandfather and son share a bond, giving and getting heck from the father, the middleman, and they can go out for ice-cream.

I enjoy teaching Indian, Greek and Chinese comparative philosophy, and if you study these subjects, you will eventually find that understanding Islamic philosophy is very helpful, but quite hard to do, because there has been a greater appreciation of Indian and Chinese culture and thought in European scholarship and counter-cultural movements that involve the Bay Area, San Francisco and Berkeley. Some have said this could be an example of the grandfather effect: If everyone in the family gives heck to the next one over, then the grandfather gives heck to the father, the father gives heck to the son, and so the grandfather and son share a bond, giving and getting heck from the father, the middleman, and they can go out for ice-cream.

Islam fought Europe, India and China, taking land, captives and converts. This is why it is easier for we, and other scholars of East and South Asia, to avoid and ignore the positive side of Islam. I have some excellent Ahadith, sayings of the prophet Mohammed, the second source of Islam after the Koran, much like the Jewish Talmud, which give a more positive view of Islam as a source of multiculturalism, science and logic: – Go in quest of knowledge, even unto China. – It is better to teach knowledge one hour in the night than to pray straight through it. – A moment’s reflection is better than 60 years devotion. – The ink of the scholar is holier than the blood of the martyrs.

Islam fought Europe, India and China, taking land, captives and converts. This is why it is easier for we, and other scholars of East and South Asia, to avoid and ignore the positive side of Islam. I have some excellent Ahadith, sayings of the prophet Mohammed, the second source of Islam after the Koran, much like the Jewish Talmud, which give a more positive view of Islam as a source of multiculturalism, science and logic: – Go in quest of knowledge, even unto China. – It is better to teach knowledge one hour in the night than to pray straight through it. – A moment’s reflection is better than 60 years devotion. – The ink of the scholar is holier than the blood of the martyrs.

Many times after quoting these lines, first to professors and fellow graduate students, and then to my own students, I have been asked how Muslims can say such things and also be so authoritarian and traditional in ways. Humanity is always capable, and in each civilization openly displays, both intelligence and ignorance, both innovation and brutality. We should use the best and the worst of Islamic civilization to better understand the best and the worst of our own. Americans are seen by many Europeans in the same light, as sex-repressed, illogical, violent people who threaten logic, decency and civilization with pride, wealth, and power.

Many times after quoting these lines, first to professors and fellow graduate students, and then to my own students, I have been asked how Muslims can say such things and also be so authoritarian and traditional in ways. Humanity is always capable, and in each civilization openly displays, both intelligence and ignorance, both innovation and brutality. We should use the best and the worst of Islamic civilization to better understand the best and the worst of our own. Americans are seen by many Europeans in the same light, as sex-repressed, illogical, violent people who threaten logic, decency and civilization with pride, wealth, and power.

Consider that 1492 was not simply the year Columbus sailed the ocean blue, for India, to get around the Muslims between India, him and Spain, but the year that Spain was reconquered from Muslims by Christians, and then Portugal soon after, as well as the first year of the Spanish Inquisition, and then the Portuguese Inquisition, the infamous persecutions of Jews and others deemed heretical by the Church. Jews and Christians who were not Catholic such as Nestorians fled to Islamic lands from Catholic persecutions. Jews went from thriving and contributing much scholarship in Islamic Spain to outright persecution and secrecy underground in a year’s time. Maimonides (1135 – 1204 CE), the famous Jewish philosopher who thankfully lived long before all of this in Cordoba, Spain, and said he read Aristotle but could not understand him at all, until he read Farabi, which solved everything to perfection.

Consider that 1492 was not simply the year Columbus sailed the ocean blue, for India, to get around the Muslims between India, him and Spain, but the year that Spain was reconquered from Muslims by Christians, and then Portugal soon after, as well as the first year of the Spanish Inquisition, and then the Portuguese Inquisition, the infamous persecutions of Jews and others deemed heretical by the Church. Jews and Christians who were not Catholic such as Nestorians fled to Islamic lands from Catholic persecutions. Jews went from thriving and contributing much scholarship in Islamic Spain to outright persecution and secrecy underground in a year’s time. Maimonides (1135 – 1204 CE), the famous Jewish philosopher who thankfully lived long before all of this in Cordoba, Spain, and said he read Aristotle but could not understand him at all, until he read Farabi, which solved everything to perfection.

Few European Christians are aware of the reverence that Muslims hold for Jesus, who is mentioned in the Quran more than anyone, the greatest prophet before Mohammed, and Mohammed isn’t mentioned much, as he’s the one hearing it from God. According to Islam, Jesus did not claim to be the solitary son of God, but rather taught that all are equally daughters and sons of God, and Muslims study the Torah and New Testaments and finding this in the words of Jesus himself. For Muslims, Jesus is the patron saint of scholars and wisdom, similar to Confucius in China, who also centers his philosophy on compassion, and Jesus sounds much like Confucius in many of the sayings attributed to him by Muslims.

Few European Christians are aware of the reverence that Muslims hold for Jesus, who is mentioned in the Quran more than anyone, the greatest prophet before Mohammed, and Mohammed isn’t mentioned much, as he’s the one hearing it from God. According to Islam, Jesus did not claim to be the solitary son of God, but rather taught that all are equally daughters and sons of God, and Muslims study the Torah and New Testaments and finding this in the words of Jesus himself. For Muslims, Jesus is the patron saint of scholars and wisdom, similar to Confucius in China, who also centers his philosophy on compassion, and Jesus sounds much like Confucius in many of the sayings attributed to him by Muslims.

The worst man is the scholar who is in error, since many people will err due to him.

The worst man is the scholar who is in error, since many people will err due to him.

The one who has learned and taught is great in the kingdom of heaven.

When asked how he could perform miracles such as walking on water, he asked in return, “Are stone, mud and gold all equal in your sight?”

When asked, “Teacher, who are the people of my race?”, Jesus said, “All the children of Adam, and that which you would not have done to yourself, do not do to others”.

When asked “Who was your teacher?”, Jesus replied, “No one taught me. I saw the ugliness of ignorance and avoided it.”

Abacus, Algebra & Abstraction

When we touch a table or look at a wall, what part of the experience is objective, and which part is subjective? Is the solidity or surface itself simply objective, and is it something different than the subjective experience and feeling we get interacting with it? It is difficult to say what is the form of the object itself and what is formed by the mind of the subject, a problem that has plagued philosophy all over the world at least since words were written down.

When we touch a table or look at a wall, what part of the experience is objective, and which part is subjective? Is the solidity or surface itself simply objective, and is it something different than the subjective experience and feeling we get interacting with it? It is difficult to say what is the form of the object itself and what is formed by the mind of the subject, a problem that has plagued philosophy all over the world at least since words were written down.

One of the most confusing things about what we call objectivity and subjectivity, which are words with several syllables that no one can simply point to or explain very well, even when they do try, is the modern contradiction of many saying logic and mathematics are symbolic abstractions, images on paper or thoughts in the mind, but also that they are the underlying objective truth, not intangibly abstract, but the reality of the real itself. We have believed in invisible spirits, gods, and laws ruling things, as their very essence, and Greek, Islamic and European logicians often speak these ways about logic and truth.

One of the most confusing things about what we call objectivity and subjectivity, which are words with several syllables that no one can simply point to or explain very well, even when they do try, is the modern contradiction of many saying logic and mathematics are symbolic abstractions, images on paper or thoughts in the mind, but also that they are the underlying objective truth, not intangibly abstract, but the reality of the real itself. We have believed in invisible spirits, gods, and laws ruling things, as their very essence, and Greek, Islamic and European logicians often speak these ways about logic and truth.

Between the ancient Greeks, such as Aristotle, who thought the gods, our superiors, are rational, but also physical, like Aristotle’s unmoved mover, and modern Europeans, such as Descartes, who thought the soul, our innermost self, is immaterial, but superior to the lowly physical body, like the gods, with no French Christian in Descartes’ time daring to say God was a physical being for fear of being tortured as a heretic, there were Muslims, like Farabi and Avicenna, who argue thought, much like we imagine math, is ideal, and mental, thus not physical, like a fire in the head of the ancient world.

Between the ancient Greeks, such as Aristotle, who thought the gods, our superiors, are rational, but also physical, like Aristotle’s unmoved mover, and modern Europeans, such as Descartes, who thought the soul, our innermost self, is immaterial, but superior to the lowly physical body, like the gods, with no French Christian in Descartes’ time daring to say God was a physical being for fear of being tortured as a heretic, there were Muslims, like Farabi and Avicenna, who argue thought, much like we imagine math, is ideal, and mental, thus not physical, like a fire in the head of the ancient world.

Muslims thus stand as a bridge between ancient polytheism, monotheism, and modern abstractions found in philosophy, science, mathematics, and logic. Islamic society developed new practices of imagination and abstraction, representing things as symbols, images, pictures and words, such as number symbols and psychological terms, and this fits the mental becoming more like an image, as something higher and meaningful, but strangely as immaterial and unreal, superior but invisible, graspable but beyond at the same time.

Muslims thus stand as a bridge between ancient polytheism, monotheism, and modern abstractions found in philosophy, science, mathematics, and logic. Islamic society developed new practices of imagination and abstraction, representing things as symbols, images, pictures and words, such as number symbols and psychological terms, and this fits the mental becoming more like an image, as something higher and meaningful, but strangely as immaterial and unreal, superior but invisible, graspable but beyond at the same time.

A base 10 system of symbols that represents reality is an easy number for us because we often have it in front of us as fingers, which often serve as a counting device, with five and five making ten together, a simple addition problem. Once we have number words we can count our fingers, as we can use our fingers to point at other things and count them. Counting boards of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome and abacuses of China also group things by tens and tens of tens to count larger groups of things with a decimal, ten-based system. The Babylonians had a six-based system we still use to tell time, with 60 minutes to an hour, and there are basic sixes in the five fingers and hand, with six including the palm for counting, as well as the head, torso, arms and legs as six. There are some tribes that count to twenty quickly using their knees, hands, feet and other parts to stand for particular numbers.

A base 10 system of symbols that represents reality is an easy number for us because we often have it in front of us as fingers, which often serve as a counting device, with five and five making ten together, a simple addition problem. Once we have number words we can count our fingers, as we can use our fingers to point at other things and count them. Counting boards of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome and abacuses of China also group things by tens and tens of tens to count larger groups of things with a decimal, ten-based system. The Babylonians had a six-based system we still use to tell time, with 60 minutes to an hour, and there are basic sixes in the five fingers and hand, with six including the palm for counting, as well as the head, torso, arms and legs as six. There are some tribes that count to twenty quickly using their knees, hands, feet and other parts to stand for particular numbers.

Beyond four or five, we lose count of things, like Danzig says of crows. On the one hand, we could say four or five good things about things, but on the other hand, we could say four or five bad things about the same things. Cultures share the words more and less before they share words for particular numbers, and then they often do not have words beyond ten or twelve, just as we say twelve but then thirteen, which is clearly three-ten in a way twelve isn’t two-ten. Beyond twelve, two sixes, countable on both hands. The word calculate is based on the Latin calculus, which means pebble, like a pebble on a counting board. To calculate, particularly before algebra replaced previous practices like counting boards and abacuses with written symbols that we can work mechanistically, as a form of language that functions like a piece of counting and calculating technology.

Beyond four or five, we lose count of things, like Danzig says of crows. On the one hand, we could say four or five good things about things, but on the other hand, we could say four or five bad things about the same things. Cultures share the words more and less before they share words for particular numbers, and then they often do not have words beyond ten or twelve, just as we say twelve but then thirteen, which is clearly three-ten in a way twelve isn’t two-ten. Beyond twelve, two sixes, countable on both hands. The word calculate is based on the Latin calculus, which means pebble, like a pebble on a counting board. To calculate, particularly before algebra replaced previous practices like counting boards and abacuses with written symbols that we can work mechanistically, as a form of language that functions like a piece of counting and calculating technology.

The Egyptians had a base 10 system, but they sometimes wrote numbers in various orders, as two ones, one ten, and three hundreds to mean three hundred and twelve, but order doesn’t matter, so 1, 1, 10, 100, 100, 100 is one way of writing it, but you could also write 1, 10, 100, 1, 100, 100 or 100, 1, 100, 10, 100, 1, as with a small number of numbers, less than five, we can count the numbers and add them together all the same. The Roman method is actually a 5 based system, as there are 5s (V), and other 5 based numbers as basic structures such that placing a one to the left or right of the five, unlike with the Egyptian method, matters.

The Egyptians had a base 10 system, but they sometimes wrote numbers in various orders, as two ones, one ten, and three hundreds to mean three hundred and twelve, but order doesn’t matter, so 1, 1, 10, 100, 100, 100 is one way of writing it, but you could also write 1, 10, 100, 1, 100, 100 or 100, 1, 100, 10, 100, 1, as with a small number of numbers, less than five, we can count the numbers and add them together all the same. The Roman method is actually a 5 based system, as there are 5s (V), and other 5 based numbers as basic structures such that placing a one to the left or right of the five, unlike with the Egyptian method, matters.

The Indian numerals, which Islamic scholars used as the basis for algebra, is even better than the Roman improvement on the Egyptian numerals, as it has an order more like the Romans, but is a simple decimal system like the Egyptians, without fives or counting backwards or forwards from them. The Roman numeral system actually has seven symbols, I, V, X, L, C, D and M, for 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000, but the Indian numeral system has ten symbols, and uses all ten to count from one to ten, unlike the Roman numerals, which make us count up or back as it uses three symbols, I (one), V (five) and X (ten) to count from one to ten. This means Roman numbers are often much longer, like the strange long dates in Roman numerals on movies only some can read, using twelve symbols to say 1981, what Indian numerals can say in four, but if we want algebra to handle long division, taking steps to determine which number between one and ten several symbols are each time is preventatively difficult.

The Indian numerals, which Islamic scholars used as the basis for algebra, is even better than the Roman improvement on the Egyptian numerals, as it has an order more like the Romans, but is a simple decimal system like the Egyptians, without fives or counting backwards or forwards from them. The Roman numeral system actually has seven symbols, I, V, X, L, C, D and M, for 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000, but the Indian numeral system has ten symbols, and uses all ten to count from one to ten, unlike the Roman numerals, which make us count up or back as it uses three symbols, I (one), V (five) and X (ten) to count from one to ten. This means Roman numbers are often much longer, like the strange long dates in Roman numerals on movies only some can read, using twelve symbols to say 1981, what Indian numerals can say in four, but if we want algebra to handle long division, taking steps to determine which number between one and ten several symbols are each time is preventatively difficult.

Before Islamic algebra, much of the world used the Egyptian doubling method (including ancient Greece and Rome) to do division. Unfortunately, this method could not keep track of remainders and could not take account of series and other functions critical to the growth of math, trade and mechanical technology. Islamic mathematicians and logicians took the Indian base 10 system, along with the Indian numerals that became our Indian-Arabic numerals we use today, and began doing math in the form of equations. Algebra allowed trade caravans to keep greater accounts of goods, as well as sophisticated forms of insurance and banking. Islamic merchants traded by caravan all the way up through Russia and Scandinavia, as coins discovered attest.

Before Islamic algebra, much of the world used the Egyptian doubling method (including ancient Greece and Rome) to do division. Unfortunately, this method could not keep track of remainders and could not take account of series and other functions critical to the growth of math, trade and mechanical technology. Islamic mathematicians and logicians took the Indian base 10 system, along with the Indian numerals that became our Indian-Arabic numerals we use today, and began doing math in the form of equations. Algebra allowed trade caravans to keep greater accounts of goods, as well as sophisticated forms of insurance and banking. Islamic merchants traded by caravan all the way up through Russia and Scandinavia, as coins discovered attest.

European Castles are modeled on Islamic questles, the Persian word for fort, far more than they are on Roman palisades, forts surrounded by log fences. Medieval dress and decoration are not modeled on Roman togas, but rather Persian and Turkish fashions. Consider hospitals with many beds, doses measured with algebra, and mechanical innovations that use gears, pistons and clocks were all passed from Islamic to European hands before Europe became wealthy and powerful. Europe owes very much to Islamic mechanics and mathematics.

European Castles are modeled on Islamic questles, the Persian word for fort, far more than they are on Roman palisades, forts surrounded by log fences. Medieval dress and decoration are not modeled on Roman togas, but rather Persian and Turkish fashions. Consider hospitals with many beds, doses measured with algebra, and mechanical innovations that use gears, pistons and clocks were all passed from Islamic to European hands before Europe became wealthy and powerful. Europe owes very much to Islamic mechanics and mathematics.

Central to logic, it was with Islamic mathematics, logic and science that equations became the language and device that structures our modern shared world. The ancient Greeks such as Euclid and Aristotle talked out problems in long spoken form. Today, many scholars use algebraic logic to explain ancient Greek ideas, but it can be quite anachronistic and misleading to do this without acknowledging Islamic contributions. For instance, the syllogisms of Aristotle seem much clearer and cleaner when presented in variables and equations of first India and then Islamic algebra. While Aristotle reasoned that if Socrates is a man, and all men are mortal, then Socrates is mortal, we today, using variables, can say that if all As are Bs, and all Bs are Cs, then all As are Cs, speaking about any groups or individuals.

Central to logic, it was with Islamic mathematics, logic and science that equations became the language and device that structures our modern shared world. The ancient Greeks such as Euclid and Aristotle talked out problems in long spoken form. Today, many scholars use algebraic logic to explain ancient Greek ideas, but it can be quite anachronistic and misleading to do this without acknowledging Islamic contributions. For instance, the syllogisms of Aristotle seem much clearer and cleaner when presented in variables and equations of first India and then Islamic algebra. While Aristotle reasoned that if Socrates is a man, and all men are mortal, then Socrates is mortal, we today, using variables, can say that if all As are Bs, and all Bs are Cs, then all As are Cs, speaking about any groups or individuals.

One of the sources of algebraic science was code-breaking or cryptography (also cryptanalysis). Between questles, codes had to be sent and algebra was used to make and break these codes. As nature was studied with mathematics, the philosophers and scientists discovered that algebra is an amazing tool for code-breaking nature. What we call “science” is still very much the mathematical decoding of nature today. Consider the constant of gravity as a hidden code or message to be discovered and phrased in algebraic language. As Islamic scientists began using algebra to crack the codes of nature, they believed that they were finding the numbers that were the thoughts and speech of God. Islamic art, which makes much use of geometric patterns, reflects this too. Isaac Newton, like many Muslim scientists, believed that mathematics is the language of nature, laws pronounced in mathematics by God over nature which cannot be contradicted.

One of the sources of algebraic science was code-breaking or cryptography (also cryptanalysis). Between questles, codes had to be sent and algebra was used to make and break these codes. As nature was studied with mathematics, the philosophers and scientists discovered that algebra is an amazing tool for code-breaking nature. What we call “science” is still very much the mathematical decoding of nature today. Consider the constant of gravity as a hidden code or message to be discovered and phrased in algebraic language. As Islamic scientists began using algebra to crack the codes of nature, they believed that they were finding the numbers that were the thoughts and speech of God. Islamic art, which makes much use of geometric patterns, reflects this too. Isaac Newton, like many Muslim scientists, believed that mathematics is the language of nature, laws pronounced in mathematics by God over nature which cannot be contradicted.

Algebraic equations allowed for Wittgenstein’s later truth table logic and other forms that we study as Logic today. However, equations present us with a new problem that was recognized by the central philosophers of the golden age of Islamic civilization: Is the world truly structured by equations, or are they a model in the human mind?

Algebraic equations allowed for Wittgenstein’s later truth table logic and other forms that we study as Logic today. However, equations present us with a new problem that was recognized by the central philosophers of the golden age of Islamic civilization: Is the world truly structured by equations, or are they a model in the human mind?

Consider the infamous proof that one equals two. Say that we start with two variables, a and b, and that they are equal. If we multiply both sides by b, then subtract a squared, then factor out (b – a), we are left with (a = b + a), which is the same thing as saying a is equal to twice itself, which is the same thing as saying that one is equal to two. How did we come to such a ridiculous conclusion?

This is one example where the mechanics of algebraic mathematics breaks down, and we have to add additional components, such as the rule that we cannot divide by zero. When we factor out (b – a) and then eliminate it, it is easy to forget that if b and a are equal, we are dividing by zero, and should be left with infinity equal to twice itself, not a equal to twice itself. The rule has to be added to the system much as a safety device has to be added to a machine to prevent it from breaking down in particular circumstances, like a safety valve that releases steam when it builds up to critical levels. This is good evidence that mathematics is a human cultural practice, not an ideal self-existent structure.

Al-Ma’mun & Al-Kindi

In 529 CE, the Roman emperor Justinian closed Plato’s Academy, which sent several prominent members to the Royal Court of Persia, what is today Iran. Greek works were translated into Syrian, and then with Islam a century later, Arabic. This is the time when Pseudo-Dionysius, a.k.a. Fake Dennis, wrote his Neo-Platonic skeptical mysticism and angelology in Syrian, a major source of Christian Platonism and philosophy, and this and other Platonic and Aristotelian works were increasingly brought to Baghdad, the seat of the Abbasid dynasty. Fake Dennis, Dionysius, is “fake” because the original Dionysius was the first Christian bishop of Athens, and the later Syrian wrote under the same name, and was thought wrongly to be him. Dionysius argued positive and negative knowing, belief and doubt, katophania and apophania, work back and forth dialectically to bring our consciousness into the greater light.

In 529 CE, the Roman emperor Justinian closed Plato’s Academy, which sent several prominent members to the Royal Court of Persia, what is today Iran. Greek works were translated into Syrian, and then with Islam a century later, Arabic. This is the time when Pseudo-Dionysius, a.k.a. Fake Dennis, wrote his Neo-Platonic skeptical mysticism and angelology in Syrian, a major source of Christian Platonism and philosophy, and this and other Platonic and Aristotelian works were increasingly brought to Baghdad, the seat of the Abbasid dynasty. Fake Dennis, Dionysius, is “fake” because the original Dionysius was the first Christian bishop of Athens, and the later Syrian wrote under the same name, and was thought wrongly to be him. Dionysius argued positive and negative knowing, belief and doubt, katophania and apophania, work back and forth dialectically to bring our consciousness into the greater light.

Debates about logic, grammar, law, theology and philosophy between Muslims, Christians and Jews in Arabic were held in royal courts for centuries from the time of Mohammed to the present day, but it was particularly in its golden age from 800 to 1200 CE, from Al-Kindi’s discussions of the scientific, experimental method to Averroes’ extensive commentaries on Aristotle. The Greek word philosophia was transliterated in Arabic as falsafa, distinguished from kalam, theology, which also involves logic, argument and debate.

Debates about logic, grammar, law, theology and philosophy between Muslims, Christians and Jews in Arabic were held in royal courts for centuries from the time of Mohammed to the present day, but it was particularly in its golden age from 800 to 1200 CE, from Al-Kindi’s discussions of the scientific, experimental method to Averroes’ extensive commentaries on Aristotle. The Greek word philosophia was transliterated in Arabic as falsafa, distinguished from kalam, theology, which also involves logic, argument and debate.

Al-Ma’mun (786-833 CE) was the most passionate caliph in supporting scholarship and science, creating an environment that encouraged free thought and debate like no other Islamic ruler. His father, al-Rashid, had diplomatic ties with Emperors of China and Charlemagne in Europe, and sent Charlemagne an elephant and elaborate brass water clock. In return, Charlemagne gave al-Rashid what may have been the world’s largest emerald. At the time, Baghdad was the largest city in the world, with a population of more than a million, far larger than Athens or Rome had ever been.

Al-Ma’mun (786-833 CE) was the most passionate caliph in supporting scholarship and science, creating an environment that encouraged free thought and debate like no other Islamic ruler. His father, al-Rashid, had diplomatic ties with Emperors of China and Charlemagne in Europe, and sent Charlemagne an elephant and elaborate brass water clock. In return, Charlemagne gave al-Rashid what may have been the world’s largest emerald. At the time, Baghdad was the largest city in the world, with a population of more than a million, far larger than Athens or Rome had ever been.

The grand vizier (minister) Ja’far, featured in the 10,001 Nights (as well as Aladdin, unfortunately as the villain) was Ma’mun’s personal tutor, and instilled in him a lifelong love of knowledge and scholarship. Ma’mun mastered theology, history, poetry, mathematics and philosophy while young, and was particularly gifted at kalam, dialectical debate and argument. Al-Ma’mun was a supporter of the Mu’tazilites, who openly questioned literal interpretations of the Qur’an, and he founded the House of Wisdom, a center for study and inquiry which drew scholars and philosophers from all over his empire to Baghdad, becoming central to the Islamic Golden Age.

The grand vizier (minister) Ja’far, featured in the 10,001 Nights (as well as Aladdin, unfortunately as the villain) was Ma’mun’s personal tutor, and instilled in him a lifelong love of knowledge and scholarship. Ma’mun mastered theology, history, poetry, mathematics and philosophy while young, and was particularly gifted at kalam, dialectical debate and argument. Al-Ma’mun was a supporter of the Mu’tazilites, who openly questioned literal interpretations of the Qur’an, and he founded the House of Wisdom, a center for study and inquiry which drew scholars and philosophers from all over his empire to Baghdad, becoming central to the Islamic Golden Age.

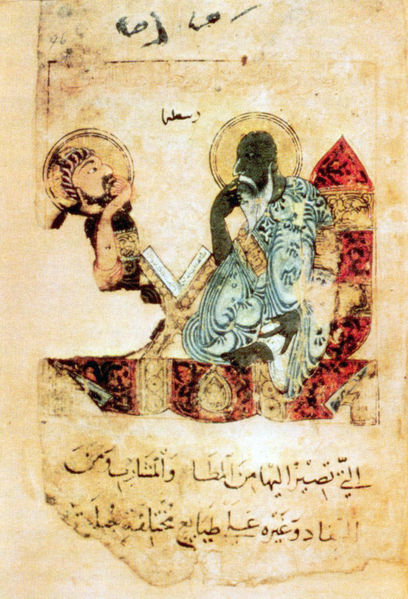

Al-Kindi (801-873), the first major Islamic philosopher, was a pioneer in the sciences, cryptography and the experimental method. He was also one of the scholars that introduced Indian numerals and base ten system to Islam, where it was developed along with other Indian as well as Greek ideas into Algebra. He wrote numerous medical treatises, including the memorable Treatise on Diseases caused by Phlegm. I still haven’t read it, but I still remember the title. Unlike Galileo and Newton, but like Einstein, Al-Kindi argued that time and space are relative, as all things save Being itself (God) are relative, subjective, and contingent, dependent on other things. Modern scholarship often says that he merged Neo-Platonism and Aristotle together, but he also incorporated Persian Zoroastrianism and Indian logic.

Al-Kindi (801-873), the first major Islamic philosopher, was a pioneer in the sciences, cryptography and the experimental method. He was also one of the scholars that introduced Indian numerals and base ten system to Islam, where it was developed along with other Indian as well as Greek ideas into Algebra. He wrote numerous medical treatises, including the memorable Treatise on Diseases caused by Phlegm. I still haven’t read it, but I still remember the title. Unlike Galileo and Newton, but like Einstein, Al-Kindi argued that time and space are relative, as all things save Being itself (God) are relative, subjective, and contingent, dependent on other things. Modern scholarship often says that he merged Neo-Platonism and Aristotle together, but he also incorporated Persian Zoroastrianism and Indian logic.

Even though Christians in Europe followed Islamic Alchemy and Astrology for centuries after al-Kindi’s death, he was an early voice against both, saying they were both pseudo-sciences and that the best method of knowledge is strict observation and experimentation. While ancient cultures observed the natural world and attempted to explain it, mechanical innovations from China as well as developments in mathematics allowed for experiments to be mechanically set up and recorded, extending beyond mere observation with experimentation. Humanity has always been experimenting with things, but cultures of regular, mechanical and mathematical experimentation became what we know as the specialized, mechanized sciences.

Even though Christians in Europe followed Islamic Alchemy and Astrology for centuries after al-Kindi’s death, he was an early voice against both, saying they were both pseudo-sciences and that the best method of knowledge is strict observation and experimentation. While ancient cultures observed the natural world and attempted to explain it, mechanical innovations from China as well as developments in mathematics allowed for experiments to be mechanically set up and recorded, extending beyond mere observation with experimentation. Humanity has always been experimenting with things, but cultures of regular, mechanical and mathematical experimentation became what we know as the specialized, mechanized sciences.

Al-Farabi, The Second Teacher

Abu Nasr al-Farabi (870 – 950 CE) is known as the Second Teacher in Islamic philosophy, as he brought Aristotelian logic into Islamic thought and made it central, which connected Boethius (d. 525 CE) to Abelard (d. 1141) in France, passing Greek logic from Roman to medieval European hands along with others. While al-Kindi (d. 866 CE) and al-Razi (d. 925) brought Greek philosophy into Islamic thought, it is al-Farabi, and following him Avicenna and Averroes, who focused on Aristotelian Peripatetic logic and what it can and can’t say.

Abu Nasr al-Farabi (870 – 950 CE) is known as the Second Teacher in Islamic philosophy, as he brought Aristotelian logic into Islamic thought and made it central, which connected Boethius (d. 525 CE) to Abelard (d. 1141) in France, passing Greek logic from Roman to medieval European hands along with others. While al-Kindi (d. 866 CE) and al-Razi (d. 925) brought Greek philosophy into Islamic thought, it is al-Farabi, and following him Avicenna and Averroes, who focused on Aristotelian Peripatetic logic and what it can and can’t say.

Farabi was born in Farab, conveniently, what is today Kazakstan, northern lands of what was Persia, and his family was Turkish, from the lands Greeks and Persians fought over in Aristotle’s time. After working as a gardener in Damascus, Syria, he moved to Baghdad and devoted himself to studying Arabic, which he didn’t know, as he spoke Turkish, as well as all the logic and philosophy he could in Syriac and Arabic with the famous logician Abu Bishr Matta (d. 911) and Ibn Haylan. Farabi was a great musician who wrote primary studies on music theory, and it is said that he once played for al-Dawlah, ruler of Aleppo, so well that he moved everyone to tears, then made them all laugh until they fell asleep, while Farabi quietly left. He wrote many books on cosmology, politics and logic, traveled, taught, and died in Damascus in 950 CE, almost 650 years before Descartes, the first major modern European philosopher, was born in France in 1594.

Farabi was born in Farab, conveniently, what is today Kazakstan, northern lands of what was Persia, and his family was Turkish, from the lands Greeks and Persians fought over in Aristotle’s time. After working as a gardener in Damascus, Syria, he moved to Baghdad and devoted himself to studying Arabic, which he didn’t know, as he spoke Turkish, as well as all the logic and philosophy he could in Syriac and Arabic with the famous logician Abu Bishr Matta (d. 911) and Ibn Haylan. Farabi was a great musician who wrote primary studies on music theory, and it is said that he once played for al-Dawlah, ruler of Aleppo, so well that he moved everyone to tears, then made them all laugh until they fell asleep, while Farabi quietly left. He wrote many books on cosmology, politics and logic, traveled, taught, and died in Damascus in 950 CE, almost 650 years before Descartes, the first major modern European philosopher, was born in France in 1594.

There was a famous debate between Abu Bishr Matta, Farabi’s teacher and leading logican of Baghdad, and al-Sirafi, a famed jurist and grammarian, in front of Vizier Ibn al-Furat in 932 CE. Matta argued logic is a tool for judging right and wrong words. Sirafi said it seems debate is a matter for grammarians, and wondered what Greek logic could do to help guard a Turk, Indian or Arab against speaking incorrectly. Matta answered that logic grasps concepts that underly all languages, such that grammar and culture are irrelevant to what is true or false in any and all languages. Islamic philosophers often mention that Islam includes many cultures together as one understanding and meaning, such as the Sufi poet Rumi, who appropriated the Indian Jain metaphor of the blind men and the elephant.

There was a famous debate between Abu Bishr Matta, Farabi’s teacher and leading logican of Baghdad, and al-Sirafi, a famed jurist and grammarian, in front of Vizier Ibn al-Furat in 932 CE. Matta argued logic is a tool for judging right and wrong words. Sirafi said it seems debate is a matter for grammarians, and wondered what Greek logic could do to help guard a Turk, Indian or Arab against speaking incorrectly. Matta answered that logic grasps concepts that underly all languages, such that grammar and culture are irrelevant to what is true or false in any and all languages. Islamic philosophers often mention that Islam includes many cultures together as one understanding and meaning, such as the Sufi poet Rumi, who appropriated the Indian Jain metaphor of the blind men and the elephant.

Al-Farabi’s theory of certainty centers on perfect agreement, on the highest certainty in what can be known and is known to not possibly be otherwise, and how Aristotle’s syllogisms, when used correctly, can provide this, which leads to happiness and fulfillment. While most people are only capable of theology, only the philosopher can learn the forms of complete agreement, which is participation with the perfect thought of God as far us mortals can. Al-Farabi studied and commented on all of the Organon, the logical works of Aristotle, and the Greek Neo-Platonist commentaries of Plotinus and Porphyry on Aristotle as well. Some, the few who have read and studied his works, say his Terms Used In Logic (al-Alfaz al-Musta’malah fi’l-Mantiq) and other introductory treatises on logic and commentaries on the Organon are unsurpassed until modern times, making more sense of Aristotle than anyone had so far, perhaps even Aristotle himself.

Al-Farabi’s theory of certainty centers on perfect agreement, on the highest certainty in what can be known and is known to not possibly be otherwise, and how Aristotle’s syllogisms, when used correctly, can provide this, which leads to happiness and fulfillment. While most people are only capable of theology, only the philosopher can learn the forms of complete agreement, which is participation with the perfect thought of God as far us mortals can. Al-Farabi studied and commented on all of the Organon, the logical works of Aristotle, and the Greek Neo-Platonist commentaries of Plotinus and Porphyry on Aristotle as well. Some, the few who have read and studied his works, say his Terms Used In Logic (al-Alfaz al-Musta’malah fi’l-Mantiq) and other introductory treatises on logic and commentaries on the Organon are unsurpassed until modern times, making more sense of Aristotle than anyone had so far, perhaps even Aristotle himself.

Farabi called his Platonism, with plenty of Aristotelianism, his foreign philosophy (al-Hikmah al-Mashriqiyah), often translated as oriental philosophy, as the word oriental was used, quite simply, to mean foreign by European translators, covering Asia, Africa and the Americas. Al-Farabi says we should borrow some, but not all of the Greek logical terms, and some from the Arabic grammarians, similar to the Hindu grammarians of India, including what, how, which and why to seek the reasons for things with logic. While grammarians, Farabi says, study the relationship between words, terms and sentences, the logicians study the relationship between concepts (ma’ani), thoughts and meanings, according to rules that Farabi thinks Aristotle began to articulate and he attempts to clarify. Farabi argues that logic (mantiq) is etymologically derived from the word for speech (nutq), and that ancient philosophers used inward speech to grasp mental concepts, the “intelligibles” of things beyond their physical form, and outward speech to point to physical objects.

Farabi called his Platonism, with plenty of Aristotelianism, his foreign philosophy (al-Hikmah al-Mashriqiyah), often translated as oriental philosophy, as the word oriental was used, quite simply, to mean foreign by European translators, covering Asia, Africa and the Americas. Al-Farabi says we should borrow some, but not all of the Greek logical terms, and some from the Arabic grammarians, similar to the Hindu grammarians of India, including what, how, which and why to seek the reasons for things with logic. While grammarians, Farabi says, study the relationship between words, terms and sentences, the logicians study the relationship between concepts (ma’ani), thoughts and meanings, according to rules that Farabi thinks Aristotle began to articulate and he attempts to clarify. Farabi argues that logic (mantiq) is etymologically derived from the word for speech (nutq), and that ancient philosophers used inward speech to grasp mental concepts, the “intelligibles” of things beyond their physical form, and outward speech to point to physical objects.

Farabi argues being (mawjud) is most fundamental to logic as a category and term, as it applies to each of the other categories, if they are categories, and exist, and it applies to things as well as what is true, what stands and exists, and being is the term closest in meaning to truth, more than any other word. Substance or stuff is jawhar, which Farabi says etymologically means jewel in Persian, possibly because substance is the most precious and primary of the categories, what is and exists, and he argues that Aristotle considered actual existing individuals primary substances, and universals secondary substances, possibly mental as opposed to physical. Farabi says that a definition (hadd) is a statement of the essential categories, while a description is a statement of accidental, inessential differences, giving us the examples Man is a rational animal, the famous statement of Aristotle, as an example of a definition, and Man is a laughing animal, sadly, as an example of mere, inessential description. Nietzsche said, “Man is the only animal that laughs, or needs to,” likely mocking Aristotle and unfamiliar with al-Farabi.

Farabi argues being (mawjud) is most fundamental to logic as a category and term, as it applies to each of the other categories, if they are categories, and exist, and it applies to things as well as what is true, what stands and exists, and being is the term closest in meaning to truth, more than any other word. Substance or stuff is jawhar, which Farabi says etymologically means jewel in Persian, possibly because substance is the most precious and primary of the categories, what is and exists, and he argues that Aristotle considered actual existing individuals primary substances, and universals secondary substances, possibly mental as opposed to physical. Farabi says that a definition (hadd) is a statement of the essential categories, while a description is a statement of accidental, inessential differences, giving us the examples Man is a rational animal, the famous statement of Aristotle, as an example of a definition, and Man is a laughing animal, sadly, as an example of mere, inessential description. Nietzsche said, “Man is the only animal that laughs, or needs to,” likely mocking Aristotle and unfamiliar with al-Farabi.

Farabi says logic is a tool that produces certainty when used properly in all arts, and in all the practical and theoretical sciences. Farabi argues, using and extending an example found in the Nyaya Sutra, that if we know that a cloud always has a rippling wind, and this wind causes the sound of thunder when clouds bump into each other, we can say, syllogistically, that the cloud causes the sound, and we can also, he adds, define thunder thus, as the sound made by rippling wind in clouds colliding, which is how it is caused, created and so speciated. A definition has two parts, genus and differendum for Aristotle, the larger group that the thing shares with other things, and what can be said of it that it is different from the other things of the same set. As such, thunder is a type of sound, and, to differentiate it from other sounds, it is specifically the sound made by rippling wind in clouds colliding.

Farabi says logic is a tool that produces certainty when used properly in all arts, and in all the practical and theoretical sciences. Farabi argues, using and extending an example found in the Nyaya Sutra, that if we know that a cloud always has a rippling wind, and this wind causes the sound of thunder when clouds bump into each other, we can say, syllogistically, that the cloud causes the sound, and we can also, he adds, define thunder thus, as the sound made by rippling wind in clouds colliding, which is how it is caused, created and so speciated. A definition has two parts, genus and differendum for Aristotle, the larger group that the thing shares with other things, and what can be said of it that it is different from the other things of the same set. As such, thunder is a type of sound, and, to differentiate it from other sounds, it is specifically the sound made by rippling wind in clouds colliding.

Farabi gives the example of a circle, which can be defined as a figure with a line with all points equidistant from the center, which means, he strangely argues, that a line itself can’t be a figure. If a figure is a larger group, and circle is a member of the set, and a certain sort of line is part of what differentiates members of the set from each other, then Farabi reasons that figure is the largest set, circle smaller, and lines incidental differences. This is odd, as reptiles can be four-footed, and so can mammals, but if all mammals and reptiles are not then neither reptile nor four-footed is simply a larger group, but rather an intersecting set, and snakes have no feet, humans have two, as Plato and Diogenes both know while arguing over a chicken. Venn diagrams are better at this than a tree of superior One differentiating into inferior many. This is also strangely similar to Hui Shi’s paradox that a four sided figure is more than four sided if it is a figure, as one side is contained by the lines but not a line itself.

Farabi gives the example of a circle, which can be defined as a figure with a line with all points equidistant from the center, which means, he strangely argues, that a line itself can’t be a figure. If a figure is a larger group, and circle is a member of the set, and a certain sort of line is part of what differentiates members of the set from each other, then Farabi reasons that figure is the largest set, circle smaller, and lines incidental differences. This is odd, as reptiles can be four-footed, and so can mammals, but if all mammals and reptiles are not then neither reptile nor four-footed is simply a larger group, but rather an intersecting set, and snakes have no feet, humans have two, as Plato and Diogenes both know while arguing over a chicken. Venn diagrams are better at this than a tree of superior One differentiating into inferior many. This is also strangely similar to Hui Shi’s paradox that a four sided figure is more than four sided if it is a figure, as one side is contained by the lines but not a line itself.

Al-Farabi argued that thought, identified Platonically with sight and the imagination, is in the heart, which can imitate what we sense to understand and represent, and create to reason and speculate. Farabi uses the example of imagining evil as symbolized by darkness, which is seeing darkness and feeling evil in the imagination. Farabi calls genius overflow of imagination. Farabi argues that poetry is good for improving the imagination, which is useful in all thinking and studied subjects, but poetry can nobly direct the rational faculty to higher forms and moderate our emotions, or it can stimulate the baser emotions and pleasures, which leads to weakness of constitution and character.

Al-Farabi argued that thought, identified Platonically with sight and the imagination, is in the heart, which can imitate what we sense to understand and represent, and create to reason and speculate. Farabi uses the example of imagining evil as symbolized by darkness, which is seeing darkness and feeling evil in the imagination. Farabi calls genius overflow of imagination. Farabi argues that poetry is good for improving the imagination, which is useful in all thinking and studied subjects, but poetry can nobly direct the rational faculty to higher forms and moderate our emotions, or it can stimulate the baser emotions and pleasures, which leads to weakness of constitution and character.

Farabi argues this is how Mohammed and other prophets teach and inspire humanity through images, metaphors and analogies, as they have an overabundance of thought, imagination and meaning that helps them see images others can feel. Angered by dismissals of Aristotle and those who studied Greek works, al Farabi argued that logic was already found in reasoning from the seen to the unseen in theology and law, and could be used to further strengthen both. Many Islamic philosophers argued, following Farabi, that philosophy and science are perfectly in accord with Islam to defend against charges of heresy, much as later European philosophers and scientists did. Many Christian scholars worked to translate Farabi’s Arabic works on logic into Latin, including Herman the German (d. 1272), who actually worked and lived in Toledo, Spain, not Ohio.

Farabi argues this is how Mohammed and other prophets teach and inspire humanity through images, metaphors and analogies, as they have an overabundance of thought, imagination and meaning that helps them see images others can feel. Angered by dismissals of Aristotle and those who studied Greek works, al Farabi argued that logic was already found in reasoning from the seen to the unseen in theology and law, and could be used to further strengthen both. Many Islamic philosophers argued, following Farabi, that philosophy and science are perfectly in accord with Islam to defend against charges of heresy, much as later European philosophers and scientists did. Many Christian scholars worked to translate Farabi’s Arabic works on logic into Latin, including Herman the German (d. 1272), who actually worked and lived in Toledo, Spain, not Ohio.

Avicenna & The Unicorn

Ibn Sina (980-1037), whose name was Latinized by Christian Europeans as Avicenna, is often called the greatest of the Islamic philosophers, much as Plato is the most popular and extensive in influence of Greek philosophers, Confucius of Chinese philosophers, Buddha of Indian philosophers, and Kant for German philosophers, for supporters and critics alike, such that the course of Islamic philosophy is taught as leading up to and then stemming from the work of Avicenna, by Islamic scholars of the golden age and today in modern scholarship. Islamic logic began in Islamic courts of law from the beginning, but by the year 1000, largely thanks to Farabi and Avicenna, Aristotelian Peripatetic logic was the dominant tradition of using logic to show strengths and faults in arguments. By 1100, Avicenna had taken Aristotle’s place as his superior. While Averroes turned back to Aristotle from Avicenna and Europeans followed him, Islamic philosophy followed Avicenna, and Averroes became more popular in Europe than he ever was in the Islamic world.

Ibn Sina (980-1037), whose name was Latinized by Christian Europeans as Avicenna, is often called the greatest of the Islamic philosophers, much as Plato is the most popular and extensive in influence of Greek philosophers, Confucius of Chinese philosophers, Buddha of Indian philosophers, and Kant for German philosophers, for supporters and critics alike, such that the course of Islamic philosophy is taught as leading up to and then stemming from the work of Avicenna, by Islamic scholars of the golden age and today in modern scholarship. Islamic logic began in Islamic courts of law from the beginning, but by the year 1000, largely thanks to Farabi and Avicenna, Aristotelian Peripatetic logic was the dominant tradition of using logic to show strengths and faults in arguments. By 1100, Avicenna had taken Aristotle’s place as his superior. While Averroes turned back to Aristotle from Avicenna and Europeans followed him, Islamic philosophy followed Avicenna, and Averroes became more popular in Europe than he ever was in the Islamic world.

Avicenna was born in the village of Afshana in what is today Uzbekistan, his father the governor of a larger, nearby village they didn’t live in, which is an interesting strategy employed today in DC. As a boy Avicenna is said to have learned Indian Arithmetic from an Indian grocer in his neighborhood, read all the Greek philosophy he could find, boiled it down in his notes to the essential points and then rearranged the points into as coherent arguments as he could, producing vast commentaries on many subjects as needed, and he claims to have learned nothing after the age of 18, having read all the texts he could by then, and then maturing year by year as he thought over what he learned.

Avicenna was born in the village of Afshana in what is today Uzbekistan, his father the governor of a larger, nearby village they didn’t live in, which is an interesting strategy employed today in DC. As a boy Avicenna is said to have learned Indian Arithmetic from an Indian grocer in his neighborhood, read all the Greek philosophy he could find, boiled it down in his notes to the essential points and then rearranged the points into as coherent arguments as he could, producing vast commentaries on many subjects as needed, and he claims to have learned nothing after the age of 18, having read all the texts he could by then, and then maturing year by year as he thought over what he learned.

Avicenna is said to be the foremost doctor of his time, and his Canon of Medicine, translated into Latin like his name, was used as a textbook for Europeans up until the 1700s, as Europe passed the Islamic world in power. His medical practice was based on experimentation and clinical trials, as al-Kindi endorses, fusing Persian, Greek, Indian and other medical traditions together. He hypothesized that diseases are caused by microscopic organisms, randomized control trials, as well as invented terms for hallucinations, insomnia, mania, dementia, epilepsy and syndromes. He was the first to correctly show the workings of the eye, arguing that light does not emanate from the mind and through the eyes in perception, as we do not see in the dark, but rather light goes into the eye from outside, contradicting Aristotle, correctly.

Avicenna is said to be the foremost doctor of his time, and his Canon of Medicine, translated into Latin like his name, was used as a textbook for Europeans up until the 1700s, as Europe passed the Islamic world in power. His medical practice was based on experimentation and clinical trials, as al-Kindi endorses, fusing Persian, Greek, Indian and other medical traditions together. He hypothesized that diseases are caused by microscopic organisms, randomized control trials, as well as invented terms for hallucinations, insomnia, mania, dementia, epilepsy and syndromes. He was the first to correctly show the workings of the eye, arguing that light does not emanate from the mind and through the eyes in perception, as we do not see in the dark, but rather light goes into the eye from outside, contradicting Aristotle, correctly.

Avicenna was an essential author for understanding Aristotle and scientific investigation, even as he argued against Aristotle on many points. Avicenna claims to use intuition (hads) to judge Aristotle and the Peripatetics, and say whether they should have come to other conclusions or not. Avicenna reinterpreted sections of Aristotle’s Prior Analytics and On Interpretation, two central books of the Organon, and this took the place of Farabi’s faithful Aristotle as the dominant theory of Islamic logic and philosophy, and interest fell away from the others. The Shamsiyya of al Katibi, one of the most popular logic textbooks in human history, focuses on formal questions of Avicenna on these topics.

Avicenna was an essential author for understanding Aristotle and scientific investigation, even as he argued against Aristotle on many points. Avicenna claims to use intuition (hads) to judge Aristotle and the Peripatetics, and say whether they should have come to other conclusions or not. Avicenna reinterpreted sections of Aristotle’s Prior Analytics and On Interpretation, two central books of the Organon, and this took the place of Farabi’s faithful Aristotle as the dominant theory of Islamic logic and philosophy, and interest fell away from the others. The Shamsiyya of al Katibi, one of the most popular logic textbooks in human history, focuses on formal questions of Avicenna on these topics.

For Avicenna, intention, or meaning is ma’nan, an idea, the form or essence apprehended by the soul or mind, much as we understand images we see to have meaning beyond the image involved with its form, as well as universal concepts and categories, which mean things, grasping necessity of being or not, beyond the thing perceived. We get the word intention in English from the Latin intentio, which was used to translate ma’nan into the Latin. As the Mad Hatter tells Alice, we really should say what we mean, and mean what we say. This is essence and existence, the mental intent and verbal form, meaning and saying together.

For Avicenna, intention, or meaning is ma’nan, an idea, the form or essence apprehended by the soul or mind, much as we understand images we see to have meaning beyond the image involved with its form, as well as universal concepts and categories, which mean things, grasping necessity of being or not, beyond the thing perceived. We get the word intention in English from the Latin intentio, which was used to translate ma’nan into the Latin. As the Mad Hatter tells Alice, we really should say what we mean, and mean what we say. This is essence and existence, the mental intent and verbal form, meaning and saying together.

Following Aristotle, Avicenna says there are many ways we grasp things as abstractions, as meanings, such as perception, in which we see color and form with the eye, common sense, imagination, memory, and the highest, intellect. It is not clear if what we call reasoning is common sense, intellect or some combination of these, along with the others, but understanding is grasping things in these ways. The Greek doctor Galen located these in the brain, as did his followers, while others, such as Farabi, located them in the heart, following Aristotle. Avicenna thinks that imagination as highest intellect is always active when we are awake, and our minds wander, or asleep, and our minds dream, but we can direct the wandering mind by placing it under the intellect, which is thinking, which involves the analysis and synthesis, splitting things apart and putting things together, of syllogistic Aristotelian reasoning.

Following Aristotle, Avicenna says there are many ways we grasp things as abstractions, as meanings, such as perception, in which we see color and form with the eye, common sense, imagination, memory, and the highest, intellect. It is not clear if what we call reasoning is common sense, intellect or some combination of these, along with the others, but understanding is grasping things in these ways. The Greek doctor Galen located these in the brain, as did his followers, while others, such as Farabi, located them in the heart, following Aristotle. Avicenna thinks that imagination as highest intellect is always active when we are awake, and our minds wander, or asleep, and our minds dream, but we can direct the wandering mind by placing it under the intellect, which is thinking, which involves the analysis and synthesis, splitting things apart and putting things together, of syllogistic Aristotelian reasoning.

Avicenna argues a sheep can see, smell, hear and, if unlucky, touch a wolf with external senses, which is all fed from the senses into fantasia, common sense. Avicenna says a sheep does not have a human intellect, but does grasp intentions, as in the wolf, what he calls estimation (wahm), what could also be called concern or care, perception of intentions, which are invisible but can be felt, not seen, smelled, heard or touched with the outer senses. The sheep cannot see danger, or the wolf’s wrath, but can put it together with a basic sort of sense which must be internal, something the mind of the sheep adds to the sights and sounds of the wolf. It is not entirely clear in the example if Avicenna means the sheep merely feels the wolf is dangerous, its own fear, or if the sheep feels the wolf’s desire, recognizing it as a creature with motives that are threatening instinctively. Avicenna argues that it is basic to the retentive imagination of the sheep, which we share but also have higher inner senses, and ultimately the imagination and intellect, giving us no clear explanation of where the sheep’s fear comes from, either from instinct or conditioning.

Avicenna argues a sheep can see, smell, hear and, if unlucky, touch a wolf with external senses, which is all fed from the senses into fantasia, common sense. Avicenna says a sheep does not have a human intellect, but does grasp intentions, as in the wolf, what he calls estimation (wahm), what could also be called concern or care, perception of intentions, which are invisible but can be felt, not seen, smelled, heard or touched with the outer senses. The sheep cannot see danger, or the wolf’s wrath, but can put it together with a basic sort of sense which must be internal, something the mind of the sheep adds to the sights and sounds of the wolf. It is not entirely clear in the example if Avicenna means the sheep merely feels the wolf is dangerous, its own fear, or if the sheep feels the wolf’s desire, recognizing it as a creature with motives that are threatening instinctively. Avicenna argues that it is basic to the retentive imagination of the sheep, which we share but also have higher inner senses, and ultimately the imagination and intellect, giving us no clear explanation of where the sheep’s fear comes from, either from instinct or conditioning.

As mentioned with Farabi, Islamic philosophers increasingly turned to the human mind and imagination as the source of reality. Consider that Avicenna, a doctor, was treating patients for hallucinations and dementia while thinking about philosophy and the mind. While Aristotle understood universals, such as the group of all elephants, as a physical set of things, Avicenna argued against Aristotle, by name, that universals are conceptions of the mind, fantasies of sense and imagination. When we speak of elephants, we are talking about our concept, not the set of elephants that currently exist. This is the great debate between essence and existence of Avicenna and Averroes. Does our term elephant refer to what we think, or all actual elephants? Averroes argued that Aristotle is right, and Avicenna is wrong, that the term does not refer to our concept of elephant, but to all physical elephants.

As mentioned with Farabi, Islamic philosophers increasingly turned to the human mind and imagination as the source of reality. Consider that Avicenna, a doctor, was treating patients for hallucinations and dementia while thinking about philosophy and the mind. While Aristotle understood universals, such as the group of all elephants, as a physical set of things, Avicenna argued against Aristotle, by name, that universals are conceptions of the mind, fantasies of sense and imagination. When we speak of elephants, we are talking about our concept, not the set of elephants that currently exist. This is the great debate between essence and existence of Avicenna and Averroes. Does our term elephant refer to what we think, or all actual elephants? Averroes argued that Aristotle is right, and Avicenna is wrong, that the term does not refer to our concept of elephant, but to all physical elephants.

Before Avicenna, the Mutazilites had argued that the most general category of thought is the thing, like Farabi says of being, and things can be further divided into existent and non-existent things. Without a thing, there is no subject for words to communicate anything. In the Quran, it says that God merely has to say to a non-existent thing, BE, and then it is. It is unclear where God finds these non-existents to talk into existence, however, and Mutazilites argued with others about whether non-existents are already in the mind of God or not, much like all possible universes necessarily existing, but in potency, as the infinite imagination of God, which God can make immediately actual.

Before Avicenna, the Mutazilites had argued that the most general category of thought is the thing, like Farabi says of being, and things can be further divided into existent and non-existent things. Without a thing, there is no subject for words to communicate anything. In the Quran, it says that God merely has to say to a non-existent thing, BE, and then it is. It is unclear where God finds these non-existents to talk into existence, however, and Mutazilites argued with others about whether non-existents are already in the mind of God or not, much like all possible universes necessarily existing, but in potency, as the infinite imagination of God, which God can make immediately actual.

The Mutazilites, like Avicenna, argued that thoughts, mental categories such as horses, are fictional and non-existent, unlike actual horses and physical objects, so thoughts are, themselves, non-existent, in the same way, they argued, that the concept of unicorns is mental, and non-existent, and so are the unicorns, which also don’t exist, unlike horses but like the idea of them. Our ideas about horses and unicorns are equally real, but imaginary, not physical, and there are physical horses our idea of horses refers to in the world, which is not true of our idea of unicorns, as far as we know from our senses, internal and external.

The Mutazilites, like Avicenna, argued that thoughts, mental categories such as horses, are fictional and non-existent, unlike actual horses and physical objects, so thoughts are, themselves, non-existent, in the same way, they argued, that the concept of unicorns is mental, and non-existent, and so are the unicorns, which also don’t exist, unlike horses but like the idea of them. Our ideas about horses and unicorns are equally real, but imaginary, not physical, and there are physical horses our idea of horses refers to in the world, which is not true of our idea of unicorns, as far as we know from our senses, internal and external.

Avicenna argued that the essence of a thing is its definition, what mental categories can properly describe and contain it, but its existence is its individuality, which is not a mental category. Many who followed Avicenna, such as Suhrawardi (d. 1191) argued essence is primary, superior to objects, while others, such as Mulla Sadra (d. 1640) argued essence is a secondary mental construct. Whether or not they took the side of Avicenna, whatever it may be, most Islamic philosophers, and many Christian Europeans, argued in terms Avicenna framed, even as many, but not all Christian European philosophers preferred traditional Aristotle and Averroes to Avicenna. Sartre, the French founder of Existentialism in the 1940s, argued that existence precedes essence, not the other way around. What he means is very different from Avicenna, that we make meaning, which is secondary to physical, disorganized and illogical existence, actual daily life, deliberately unhinged from the thought of God, taking after Nietzsche.

Avicenna argued that the essence of a thing is its definition, what mental categories can properly describe and contain it, but its existence is its individuality, which is not a mental category. Many who followed Avicenna, such as Suhrawardi (d. 1191) argued essence is primary, superior to objects, while others, such as Mulla Sadra (d. 1640) argued essence is a secondary mental construct. Whether or not they took the side of Avicenna, whatever it may be, most Islamic philosophers, and many Christian Europeans, argued in terms Avicenna framed, even as many, but not all Christian European philosophers preferred traditional Aristotle and Averroes to Avicenna. Sartre, the French founder of Existentialism in the 1940s, argued that existence precedes essence, not the other way around. What he means is very different from Avicenna, that we make meaning, which is secondary to physical, disorganized and illogical existence, actual daily life, deliberately unhinged from the thought of God, taking after Nietzsche.