For this lecture, read Book I and II of Gautama’s Nyaya Sutra.

For this lecture, read Book I and II of Gautama’s Nyaya Sutra.

Six orthodox Hindu schools and three unorthodox non-Hindu schools of thought flourished in the golden age of Indian philosophy and classical culture. Many today say there was a loose association of proto-Hindu culture as Mahavira founded Jainism around 650 BCE, the first major non-Hindu, unorthodox school, and the six schools of orthodox Hinduism and the unorthodox schools of Buddhism and the Charvakas formed in reaction to Jainism’s early dominance in Northern India, the same place where the Buddha founded Buddhism around 550 BCE.

There is much to say about all of these schools, but we are going to focus on Indian logic, so we will be covering the logical debate tactics and teachings of the unorthodox Charvakas, Jains and Buddhists first, and then, after considering the Hindu Vaisheshika school of Kanada, we will focus most and last on the Hindu Nyaya school of Gautama, who most resembles Aristotle in ancient India and who lived around the time of the Buddha, who is also confusingly known as Gautama, as they both come from the same region of Northern India around the same time.

There is much to say about all of these schools, but we are going to focus on Indian logic, so we will be covering the logical debate tactics and teachings of the unorthodox Charvakas, Jains and Buddhists first, and then, after considering the Hindu Vaisheshika school of Kanada, we will focus most and last on the Hindu Nyaya school of Gautama, who most resembles Aristotle in ancient India and who lived around the time of the Buddha, who is also confusingly known as Gautama, as they both come from the same region of Northern India around the same time.

The Charvakas & Logic as Illusion

The Charvakas were a very skeptical group of thinkers who didn’t survive long as a school, much like the Russian Nihilists of the 1800s. However, they are certainly worth mentioning, as like Indian thought, and the Buddhists, and the Nyaya logicians, they place central emphasis on perception, on reality as primarily sensed and felt with the body, seen with the eyes, and heard with the ears, not on words or forms of thought.

The Charvakas were a very skeptical group of thinkers who didn’t survive long as a school, much like the Russian Nihilists of the 1800s. However, they are certainly worth mentioning, as like Indian thought, and the Buddhists, and the Nyaya logicians, they place central emphasis on perception, on reality as primarily sensed and felt with the body, seen with the eyes, and heard with the ears, not on words or forms of thought.

All of these schools argue that if we speak less and think less, paying attention to what we feel, see and hear, we find the underlying truth, but the Charvakas, unlike the Buddhists, who study the many impermanent forms of mind and reality that lead us beyond what we perceive, and unlike the Nyaya, who study what words and thoughts can be justified given what we perceive, the Charvakas most skeptically and subjectively argued that there is no reality to words or thought outside what we experience in the present moment.

All of these schools argue that if we speak less and think less, paying attention to what we feel, see and hear, we find the underlying truth, but the Charvakas, unlike the Buddhists, who study the many impermanent forms of mind and reality that lead us beyond what we perceive, and unlike the Nyaya, who study what words and thoughts can be justified given what we perceive, the Charvakas most skeptically and subjectively argued that there is no reality to words or thought outside what we experience in the present moment.

The Vaisheshika and the Nyaya Hindu logicians argue about justifiable inference and judgement, about what can be said given what we know, just like Aristotle, but the Charvakas did not believe in inference or theory of any kind, nor did they believe in gods or an eternal soul. One can use thought as a tool, and it is useful for all of us to believe in ancient India, which we will each likely never see, but it is always an imaginary illusion. Only what is right in front of your eyes is real.

The Vaisheshika and the Nyaya Hindu logicians argue about justifiable inference and judgement, about what can be said given what we know, just like Aristotle, but the Charvakas did not believe in inference or theory of any kind, nor did they believe in gods or an eternal soul. One can use thought as a tool, and it is useful for all of us to believe in ancient India, which we will each likely never see, but it is always an imaginary illusion. Only what is right in front of your eyes is real.

This is very similar to Wittgenstein’s famous opening line of the Tractatus, the book that began modern truth table logic: “The world consists of facts, not of things”. If we consider how much of our reality is imagined, like the street outside, or our parents, even if we imagine they independently exist, we have to imagine that we imagine they exist or not, as we can’t see that we are imagining or not with our eyes. We imagine rain always requires clouds, but we cannot perceive all rain or all clouds or the connection between the two. The Charvakas say that thoughts and consciousness arise, like fermented alcohol, and then it evaporates.

This is very similar to Wittgenstein’s famous opening line of the Tractatus, the book that began modern truth table logic: “The world consists of facts, not of things”. If we consider how much of our reality is imagined, like the street outside, or our parents, even if we imagine they independently exist, we have to imagine that we imagine they exist or not, as we can’t see that we are imagining or not with our eyes. We imagine rain always requires clouds, but we cannot perceive all rain or all clouds or the connection between the two. The Charvakas say that thoughts and consciousness arise, like fermented alcohol, and then it evaporates.

Jainism & Skeptical Perspectives

One of the major differences between the unorthodox non-Hindu schools of Indian thought and the orthodox Hindu schools of the Vaisheshika and Nyaya was what Greek and German philosophers call the endless dialectic between dogmatism and skepticism. Hindu schools attempt to establish truth as objective, fixed and universal, and the skeptical non-Hindu schools, the most famous and popular being the Buddhists, debate them, arguing that truth is subjective, changing and particular. These are positions found between Greek, Chinese, Islamic and European thinkers we will continue to study.

One of the major differences between the unorthodox non-Hindu schools of Indian thought and the orthodox Hindu schools of the Vaisheshika and Nyaya was what Greek and German philosophers call the endless dialectic between dogmatism and skepticism. Hindu schools attempt to establish truth as objective, fixed and universal, and the skeptical non-Hindu schools, the most famous and popular being the Buddhists, debate them, arguing that truth is subjective, changing and particular. These are positions found between Greek, Chinese, Islamic and European thinkers we will continue to study.

The Jains, who were some of the first to venture into the jungle, dissatisfied with traditional Hindu culture, embrace radical simplicity and non-violence, famed for meditating naked for long periods of time to discipline the mind and body. They are also credited with articulating three doctrines of skepticism and relativity, often called ‘principles’, but more perspectives and points of view, tools for understanding truth and meaning, than they are laws or commandments given in words. All three are intended to encourage acceptance and neutrality towards others and their perspectives, particularly when their understandings and interests conflict with our own.

The Jains, who were some of the first to venture into the jungle, dissatisfied with traditional Hindu culture, embrace radical simplicity and non-violence, famed for meditating naked for long periods of time to discipline the mind and body. They are also credited with articulating three doctrines of skepticism and relativity, often called ‘principles’, but more perspectives and points of view, tools for understanding truth and meaning, than they are laws or commandments given in words. All three are intended to encourage acceptance and neutrality towards others and their perspectives, particularly when their understandings and interests conflict with our own.

First is anekantavada, the non-one-sided-view (vada) that things are some-and-some-not rather than all-or-none, shades of grey rather than black and white, somewhat good, somewhat bad, somewhat true, somewhat false, somewhat known and somewhat unknown. Things that are good are somewhat good in some ways, just as things that are said are somewhat true in some ways. Jains argue against doctrines they consider ekantavada, one-sided and dogmatic. Around 700 CE, fourteen hundred years after Mahavira, the Jain Svetambara monk Haribhadrasuri wrote an influential work entitled Anekantajayapataka, often translated as The Victory Flag of Relativity.

First is anekantavada, the non-one-sided-view (vada) that things are some-and-some-not rather than all-or-none, shades of grey rather than black and white, somewhat good, somewhat bad, somewhat true, somewhat false, somewhat known and somewhat unknown. Things that are good are somewhat good in some ways, just as things that are said are somewhat true in some ways. Jains argue against doctrines they consider ekantavada, one-sided and dogmatic. Around 700 CE, fourteen hundred years after Mahavira, the Jain Svetambara monk Haribhadrasuri wrote an influential work entitled Anekantajayapataka, often translated as The Victory Flag of Relativity.

Second is nayavada, the perspective-view that things are known from a particular perspective in a particular situation rather than known universally for all times and places. Third is syadvada, the maybe-view, that things are known and understood hypothetically, as if our evidence, perspective and reasoning are reliable, rather than known certainly without the possibility of being wrong. The Jains, in debate with Buddhists and the Nyaya Hindu school, consider the four sources of evidence (perception, inference, comparison and testimony) of the Nyaya to be somewhat reliable but also somewhat unreliable.

Second is nayavada, the perspective-view that things are known from a particular perspective in a particular situation rather than known universally for all times and places. Third is syadvada, the maybe-view, that things are known and understood hypothetically, as if our evidence, perspective and reasoning are reliable, rather than known certainly without the possibility of being wrong. The Jains, in debate with Buddhists and the Nyaya Hindu school, consider the four sources of evidence (perception, inference, comparison and testimony) of the Nyaya to be somewhat reliable but also somewhat unreliable.

The famous parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant is a Jain story which is known throughout the world and used to teach this idea. Just as each blind man directly experiences part of the elephant through direct contact, but mistakenly argues against the others who each experience their own part of the whole, projecting and imagining beyond direct perception, Jains argue that there is truth in all religions, philosophies, ideologies, perspectives and points of view, and there are many paths up the same mountain and many rivers that feed into the same ocean. In debate, Jains make sure to first point out how there opponent is right, and then go on to show how each school other than theirs has some of the truth, but not all sides of it.

The famous parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant is a Jain story which is known throughout the world and used to teach this idea. Just as each blind man directly experiences part of the elephant through direct contact, but mistakenly argues against the others who each experience their own part of the whole, projecting and imagining beyond direct perception, Jains argue that there is truth in all religions, philosophies, ideologies, perspectives and points of view, and there are many paths up the same mountain and many rivers that feed into the same ocean. In debate, Jains make sure to first point out how there opponent is right, and then go on to show how each school other than theirs has some of the truth, but not all sides of it.

Another Jain parable used to illustrate these principles is The Golden Crown, a simple story about a king with a crown, a prince who desires it and a queen who wants it melted down and made into a necklace. Much as time transforms the old into the new by way of desire, the king agrees with the queen and melts down the crown, making the prince sad. Whether or not the king decides to melt down the necklace and reform the crown, making the queen sad and the prince happy, the king remains happy no matter what happens, as the king cares about the gold, and it remains constant regardless of its temporary form. Whether or not the prince or queen get a reality that coincides with their perspectives and interests, the king retains a perspective that always coincides with his interests, no matter what happens or who wins.

Another Jain parable used to illustrate these principles is The Golden Crown, a simple story about a king with a crown, a prince who desires it and a queen who wants it melted down and made into a necklace. Much as time transforms the old into the new by way of desire, the king agrees with the queen and melts down the crown, making the prince sad. Whether or not the king decides to melt down the necklace and reform the crown, making the queen sad and the prince happy, the king remains happy no matter what happens, as the king cares about the gold, and it remains constant regardless of its temporary form. Whether or not the prince or queen get a reality that coincides with their perspectives and interests, the king retains a perspective that always coincides with his interests, no matter what happens or who wins.

Jains, like Buddhists, believe that things may or may not be as they seem and may or may not be expressible as they are, and that there are seven points of view as to how describable and conceivable anything is. Each thing, including the cosmos and the self IS in a way that is describable, IS NOT in a way that is describable, IS and IS NOT in a way that is describable, IS indescribable, IS in a way that is indescribable, IS NOT in a way that is indescribable, and IS and IS NOT in a way that is indescribable. No, I will not make you come up with examples for this week’s assignment.

Jains, like Buddhists, believe that things may or may not be as they seem and may or may not be expressible as they are, and that there are seven points of view as to how describable and conceivable anything is. Each thing, including the cosmos and the self IS in a way that is describable, IS NOT in a way that is describable, IS and IS NOT in a way that is describable, IS indescribable, IS in a way that is indescribable, IS NOT in a way that is indescribable, and IS and IS NOT in a way that is indescribable. No, I will not make you come up with examples for this week’s assignment.

Nagarjuna, the greatest of Buddhist logicians, was likely thinking of these and other formulas as he formulated his Catuskoti (Four Things), as the Buddhists and others borrow much from the Jains and Nyaya. Nagarjuna argues that each thing IS, IS NOT, both IS and IS NOT, and neither IS nor IS NOT. Nagarjuna seems to have realized that if describable and indescribable are two more ways things are or are-not, then we can boil the seven things down to four. If we have two circles, the first being IS, and the second being IS NOT, then the space shared by the two both IS and IS NOT, and the area outside the two circles neither IS nor IS NOT.

Nagarjuna, the greatest of Buddhist logicians, was likely thinking of these and other formulas as he formulated his Catuskoti (Four Things), as the Buddhists and others borrow much from the Jains and Nyaya. Nagarjuna argues that each thing IS, IS NOT, both IS and IS NOT, and neither IS nor IS NOT. Nagarjuna seems to have realized that if describable and indescribable are two more ways things are or are-not, then we can boil the seven things down to four. If we have two circles, the first being IS, and the second being IS NOT, then the space shared by the two both IS and IS NOT, and the area outside the two circles neither IS nor IS NOT.

For example, if we consider the example fire is hot, an objective and absolute truth according to Nyaya logicians, then it is also true that, in some way, fire is not hot (relative to the plasma in a star), fire is both hot and not (hotter than some things, but not others), fire is neither hot nor not hot (is neither the hottest nor the coldest thing), and that fire being hot, fire being not hot, fire being both hot and not hot, and fire being neither hot nor not are each describable, indescribable, both and neither. For the Jains, the completely indescribable is qualified as neither IS nor NOT.

For example, if we consider the example fire is hot, an objective and absolute truth according to Nyaya logicians, then it is also true that, in some way, fire is not hot (relative to the plasma in a star), fire is both hot and not (hotter than some things, but not others), fire is neither hot nor not hot (is neither the hottest nor the coldest thing), and that fire being hot, fire being not hot, fire being both hot and not hot, and fire being neither hot nor not are each describable, indescribable, both and neither. For the Jains, the completely indescribable is qualified as neither IS nor NOT.

To illustrate the fourth of the four things, consider an image of a fire. It is not hot because it is an image, but it is not cold as a consequence of not being hot either. Rather, the image of a fire is neither hot nor cold in itself unless one has left the television on for far too long. Another example of this type is an actor playing a villain is not bad because he does evil on screen, but neither is he good because he is not evil as he appears. The actor may be acting well or poorly regardless of what the role requires.

To illustrate the fourth of the four things, consider an image of a fire. It is not hot because it is an image, but it is not cold as a consequence of not being hot either. Rather, the image of a fire is neither hot nor cold in itself unless one has left the television on for far too long. Another example of this type is an actor playing a villain is not bad because he does evil on screen, but neither is he good because he is not evil as he appears. The actor may be acting well or poorly regardless of what the role requires.

In one debate, Nagarjuna’s opponent argues that if Nagarjuna believes everything is empty, then his words and argument must also be empty. Nagarjuna replies that this does not mean they are not also true and meaningful at the same time. What will these words we use now mean next week, or in 3000 years? They might be quite meaningless then, but this does not make them meaningless here and now. Nagarjuna’s opponent argues that if Nagarjuna believes that everything can be negated, then so can his argument. Nagarjuna replies that he can negate his own argument, but he can also put it forward at the same time.

In one debate, Nagarjuna’s opponent argues that if Nagarjuna believes everything is empty, then his words and argument must also be empty. Nagarjuna replies that this does not mean they are not also true and meaningful at the same time. What will these words we use now mean next week, or in 3000 years? They might be quite meaningless then, but this does not make them meaningless here and now. Nagarjuna’s opponent argues that if Nagarjuna believes that everything can be negated, then so can his argument. Nagarjuna replies that he can negate his own argument, but he can also put it forward at the same time.

Nagarjuna taught that all Buddhist concepts are only valid for actual practice and not abstractly in theory, much like American pragmatists such as Dewey and Rorty. Like Wittgenstein in his later thought, Nagarjuna taught that things do not have singular essences, but arise out of the complex. He argued this against other Buddhist schools of his time who taught that the essence of the self is non-existence as opposed to existence, that time is the essence of things, anger is the essence of duality, that compassion is the essence of practice, and matter is the essence of form. Each of these things are true, but not entirely and exclusively true.

Nagarjuna taught that all Buddhist concepts are only valid for actual practice and not abstractly in theory, much like American pragmatists such as Dewey and Rorty. Like Wittgenstein in his later thought, Nagarjuna taught that things do not have singular essences, but arise out of the complex. He argued this against other Buddhist schools of his time who taught that the essence of the self is non-existence as opposed to existence, that time is the essence of things, anger is the essence of duality, that compassion is the essence of practice, and matter is the essence of form. Each of these things are true, but not entirely and exclusively true.

While other schools, including Nyaya logicians, claimed that Jains and Buddhists are at fault for contradicting themselves and seeing contradicting views in things, the Jains and Buddhists argue that we only fall into problematic contradiction if we make one-sided (ekanta) claims about things, ignoring the legitimate contradictory opposite side. Jain texts use the example of hot and cold. We could supply the modern example of a refrigerator, which cools on the inside by heating up in back and drawing the heat out of the inside. A refrigerator is simultaneously hot and cold, and it could not be cold in one part unless it is hot in another.

While other schools, including Nyaya logicians, claimed that Jains and Buddhists are at fault for contradicting themselves and seeing contradicting views in things, the Jains and Buddhists argue that we only fall into problematic contradiction if we make one-sided (ekanta) claims about things, ignoring the legitimate contradictory opposite side. Jain texts use the example of hot and cold. We could supply the modern example of a refrigerator, which cools on the inside by heating up in back and drawing the heat out of the inside. A refrigerator is simultaneously hot and cold, and it could not be cold in one part unless it is hot in another.

Jains also use the example of a pot as both being and non-being, solid and empty, there and not there as a particular arrangement, much as Laozi says in chapter 11 of the Daodejing that a wheel or a room is an arrangement of being and non-being together. Jains and Buddhists also use the example of a multicolored cloth, which is and is not many colors all over, which can be found in the Nyaya Sutra as a metaphor used by their skeptical opponents. Because human views and descriptions are always one-sided and partial given change, it is perfectly alright to understand the whole yet lead people in one direction as opposed to another if one sees what one is doing.

Jains also use the example of a pot as both being and non-being, solid and empty, there and not there as a particular arrangement, much as Laozi says in chapter 11 of the Daodejing that a wheel or a room is an arrangement of being and non-being together. Jains and Buddhists also use the example of a multicolored cloth, which is and is not many colors all over, which can be found in the Nyaya Sutra as a metaphor used by their skeptical opponents. Because human views and descriptions are always one-sided and partial given change, it is perfectly alright to understand the whole yet lead people in one direction as opposed to another if one sees what one is doing.

The Vaisheshika, Atoms & Investigation

Kanada, like the country but with a K, is the founder of the Vaisheshika school and his name means one who eats grain, but it could also mean one who gathers particulars or particles into larger groups, and he was one of the first atomists and logicians in human history. He is also known as the Owl (Uluka). Legend has it that he was so ugly in appearance that he frightened young women, so he only ventured out at night, sneaking into granaries to eat corn and rice grains/particles. Another story is Shiva taught him in the form of an owl. Vaisheshika also means particular, but also particle, atom, particular, special, specific, and distinction.

Kanada, like the country but with a K, is the founder of the Vaisheshika school and his name means one who eats grain, but it could also mean one who gathers particulars or particles into larger groups, and he was one of the first atomists and logicians in human history. He is also known as the Owl (Uluka). Legend has it that he was so ugly in appearance that he frightened young women, so he only ventured out at night, sneaking into granaries to eat corn and rice grains/particles. Another story is Shiva taught him in the form of an owl. Vaisheshika also means particular, but also particle, atom, particular, special, specific, and distinction.

Gautama’s Nyaya school, who study logic and debate, borrowed much from Kanada’s Vaisheshika school, who more study cosmology and how nature works. Aristotle studied both these subjects in Athens just after Kanada and Gautama, and like Aristotle, Kanada and Gautama were particularly focused on inherence, how individual particular things are gathered into groups in the world, and inference, how our minds draw logical conclusions from these groups. For example, both Gautama and Aristotle likely argued, whether or not they wrote the works associated with their names, that if something is a cow, then it certainly has four feet and horns, like an ox but unlike a bird. Kanada and Gautama’s texts argue that all cows have dewlaps, the hanging skin found in the neck-folds of sacred Indian cows.

Gautama’s Nyaya school, who study logic and debate, borrowed much from Kanada’s Vaisheshika school, who more study cosmology and how nature works. Aristotle studied both these subjects in Athens just after Kanada and Gautama, and like Aristotle, Kanada and Gautama were particularly focused on inherence, how individual particular things are gathered into groups in the world, and inference, how our minds draw logical conclusions from these groups. For example, both Gautama and Aristotle likely argued, whether or not they wrote the works associated with their names, that if something is a cow, then it certainly has four feet and horns, like an ox but unlike a bird. Kanada and Gautama’s texts argue that all cows have dewlaps, the hanging skin found in the neck-folds of sacred Indian cows.

Kanada argued there are many objects of knowledge, including substances such as air, water, fire, earth, ether, time, space, self and mind, composed of particles or atoms that are eternal and uncreated, and thus can’t be created or destroyed, attributes such as quality (color, texture, odor, taste) and quantity (number, measure, distinction, conjunction, disjunction), actions (karma) such as kicking someone, they feel pain and you are later reborn a cockroach, generals, such as the group of all cows or rainstorms, particulars, such as individual cows or rain clouds, inherences, the individual cow having four feet or the rain cloud leading to rain, and emptiness, non-being and types of absence.

Kanada argued there are many objects of knowledge, including substances such as air, water, fire, earth, ether, time, space, self and mind, composed of particles or atoms that are eternal and uncreated, and thus can’t be created or destroyed, attributes such as quality (color, texture, odor, taste) and quantity (number, measure, distinction, conjunction, disjunction), actions (karma) such as kicking someone, they feel pain and you are later reborn a cockroach, generals, such as the group of all cows or rainstorms, particulars, such as individual cows or rain clouds, inherences, the individual cow having four feet or the rain cloud leading to rain, and emptiness, non-being and types of absence.

Kanada argues action belongs to one substance, not many. It is very possible that, in opposition to this theory, the Buddhist sound of one hand clapping is a counter example to this. While the Zen koan has value as a contemplation device, it is also contemplating the impossibility of sound, an action, being produced exclusively by one thing but rather by the desire to clap, two hands, the air as medium, and everything situated together, what Buddhists call codependent arising. Kanada argues that sound is caused and therefore it is impermanent. This could be a subtle critique of the oral Vedic tradition, promoting philosophy and science as a route to the divine and objective, beyond traditional Hindu devotional practices.

Kanada argues action belongs to one substance, not many. It is very possible that, in opposition to this theory, the Buddhist sound of one hand clapping is a counter example to this. While the Zen koan has value as a contemplation device, it is also contemplating the impossibility of sound, an action, being produced exclusively by one thing but rather by the desire to clap, two hands, the air as medium, and everything situated together, what Buddhists call codependent arising. Kanada argues that sound is caused and therefore it is impermanent. This could be a subtle critique of the oral Vedic tradition, promoting philosophy and science as a route to the divine and objective, beyond traditional Hindu devotional practices.

Kanada also argues in the Vaisheshika Sutra that things move downward naturally, so things must have additional causes or forces to move sideways or upward. For example, Kanada says smoke shows additional energy, as it has fire in it and fire moves upward, and water moves upward by sun and fire in it, collects in clouds, the fire is released as lightning, and the water comes downward in cycles. He argues that the arrow flies first from cause and then from an inherent tendency to remain in motion, similar if not identical to Newton’s concept of inertia.

Kanada also argues in the Vaisheshika Sutra that things move downward naturally, so things must have additional causes or forces to move sideways or upward. For example, Kanada says smoke shows additional energy, as it has fire in it and fire moves upward, and water moves upward by sun and fire in it, collects in clouds, the fire is released as lightning, and the water comes downward in cycles. He argues that the arrow flies first from cause and then from an inherent tendency to remain in motion, similar if not identical to Newton’s concept of inertia.

The Nyaya Sutra, Logic & Debate

Gautama is the founder of the Nyaya school and the author of the Nyaya Sutra, the greatest text on logical debate of ancient India, and he is also known as Akshapada, (eyes in the feet, or gazes at his feet), which, like Kanada’s name, could mean someone who is gathering up many particular things in the lower world into higher universal concepts, or someone lost in thought, much as Thales, the first famed Greek thinker, was gazing at the stars as he fell into a well. A legend says that the same happened to Gautama, who fell into a well while lost in thought, so Brahma gave him eyes in his feet.

Gautama is the founder of the Nyaya school and the author of the Nyaya Sutra, the greatest text on logical debate of ancient India, and he is also known as Akshapada, (eyes in the feet, or gazes at his feet), which, like Kanada’s name, could mean someone who is gathering up many particular things in the lower world into higher universal concepts, or someone lost in thought, much as Thales, the first famed Greek thinker, was gazing at the stars as he fell into a well. A legend says that the same happened to Gautama, who fell into a well while lost in thought, so Brahma gave him eyes in his feet.

Nyaya means right, just, justified or justifiable, the same way we use logical to mean justifiable and defendable debate or speech. The Nyaya school reached its height in 150 CE, but it traces itself back to Gautama and his teachings. In ancient India, a king, authority or rich patron could organize a debate and banquet, invite participants from various schools of thought to debate. A story from the period says that a scholar who gave up on the Vedas and turned entirely to logic turned into a Jackal. This story was obviously told by Vedic scholars and priests who found the new systems a threat to the old established traditions. The other famed Nyaya logicians, each writing commentaries on the Nyaya Sutra of Gautama and the others before them, are Vatsyayana (c. 450 CE), Uddyotakara (c. 550 CE), Vacaspatimishra (c. 900 CE) and Udayana (c. 1000 CE).

Nyaya means right, just, justified or justifiable, the same way we use logical to mean justifiable and defendable debate or speech. The Nyaya school reached its height in 150 CE, but it traces itself back to Gautama and his teachings. In ancient India, a king, authority or rich patron could organize a debate and banquet, invite participants from various schools of thought to debate. A story from the period says that a scholar who gave up on the Vedas and turned entirely to logic turned into a Jackal. This story was obviously told by Vedic scholars and priests who found the new systems a threat to the old established traditions. The other famed Nyaya logicians, each writing commentaries on the Nyaya Sutra of Gautama and the others before them, are Vatsyayana (c. 450 CE), Uddyotakara (c. 550 CE), Vacaspatimishra (c. 900 CE) and Udayana (c. 1000 CE).

The Nyaya Sutra presents many debates that raged at the time, with many centered on dividing the mortal and particular from the eternal and universal, such as whether or not the self, or world, or laws of the cosmos are permanent or fixed in this or that way. One of these questions, asked previously by Kanada, is whether or not sound is temporary, and Kanada, like a Buddhist, says it is, though Kanada and the Nyaya following Gautama would insist that the self and laws of the cosmos, unlike sound, are eternal, following orthodox, established Hindu positions. These debates, as well as those about whether or not luxury or pleasure are good or bad, often take the form of a basic bifurcating disjunction: Is A B or not-B? Vedic priests argued that the individual self is eternal, while the Charvakas and Buddhists argued that it is temporary. Buddhists who debated the Nyaya often used relative qualifiers such as A is sometimes B, or A is somewhere B, or A is B in some things, in some ways.

The Nyaya Sutra presents many debates that raged at the time, with many centered on dividing the mortal and particular from the eternal and universal, such as whether or not the self, or world, or laws of the cosmos are permanent or fixed in this or that way. One of these questions, asked previously by Kanada, is whether or not sound is temporary, and Kanada, like a Buddhist, says it is, though Kanada and the Nyaya following Gautama would insist that the self and laws of the cosmos, unlike sound, are eternal, following orthodox, established Hindu positions. These debates, as well as those about whether or not luxury or pleasure are good or bad, often take the form of a basic bifurcating disjunction: Is A B or not-B? Vedic priests argued that the individual self is eternal, while the Charvakas and Buddhists argued that it is temporary. Buddhists who debated the Nyaya often used relative qualifiers such as A is sometimes B, or A is somewhere B, or A is B in some things, in some ways.

Gautama and the Nyaya base their entire system, which they argue, like the world, is a coherent, positive whole, on one source of knowledge, perception, as the Charvakas do, but they also argue that there are three other sources of knowledge that serve as bases for justifiable positions, beliefs and arguments, inference, as do the Vaisheshika, but also comparison (which some translate as analogy, an extensive comparison) and testimony, like the evidence of a witness in court for something we didn’t see. Thus, there are four sources (pramana) of knowledge for the Nyaya, but the later three are secondary and inferior to the first, direct experience of what we infer, compare or hear about through testimony of others.

Gautama and the Nyaya base their entire system, which they argue, like the world, is a coherent, positive whole, on one source of knowledge, perception, as the Charvakas do, but they also argue that there are three other sources of knowledge that serve as bases for justifiable positions, beliefs and arguments, inference, as do the Vaisheshika, but also comparison (which some translate as analogy, an extensive comparison) and testimony, like the evidence of a witness in court for something we didn’t see. Thus, there are four sources (pramana) of knowledge for the Nyaya, but the later three are secondary and inferior to the first, direct experience of what we infer, compare or hear about through testimony of others.

The word pramana, which the Nyaya use for source, foundation, or evidence, means proof, and comes from the word roots for out from (pra) and measurement (ma), such that measuring out things to judge them is talking things out in debate. The Buddhists refer to it as pramanavada, the way or viewpoint of measuring things out. The Nyaya argue a proper understanding of the inventory of reality is important to act effectively, assuming reality has an order independent of our minds and cultural practices. Vatsyayana, the foremost Nyaya logician after Gautama, says that all of the Nyaya method is investigation of subjects by means of sources, and Uddyotakara says the best reasoning involves many sources to establish a position well.

The word pramana, which the Nyaya use for source, foundation, or evidence, means proof, and comes from the word roots for out from (pra) and measurement (ma), such that measuring out things to judge them is talking things out in debate. The Buddhists refer to it as pramanavada, the way or viewpoint of measuring things out. The Nyaya argue a proper understanding of the inventory of reality is important to act effectively, assuming reality has an order independent of our minds and cultural practices. Vatsyayana, the foremost Nyaya logician after Gautama, says that all of the Nyaya method is investigation of subjects by means of sources, and Uddyotakara says the best reasoning involves many sources to establish a position well.

The Nyaya lean towards “innocent until legitimate doubt” about belief, which means they lean towards positive belief, unless things are disproven or there is some evidence against them. Inferences can be hastily drawn, but if they are drawn slowly, based in good, careful reason, we should entertain them positively and favorably, not as certain but as openly possible. The same is true of perception, comparison and testimony, such that they are overall reliable, if we are careful with them. If a belief that exists is doubtable, we should investigate it with sources and testing possibilities, using hypothetical reasoning (tarka). The Charvakas, Buddhists, and other skeptics doubt that conviction and coherence is what we need as opposed to tranquility and perspective. In the beginning of Vatsyayana’s commentary on the Nyaya Sutra, he argues:

The Nyaya lean towards “innocent until legitimate doubt” about belief, which means they lean towards positive belief, unless things are disproven or there is some evidence against them. Inferences can be hastily drawn, but if they are drawn slowly, based in good, careful reason, we should entertain them positively and favorably, not as certain but as openly possible. The same is true of perception, comparison and testimony, such that they are overall reliable, if we are careful with them. If a belief that exists is doubtable, we should investigate it with sources and testing possibilities, using hypothetical reasoning (tarka). The Charvakas, Buddhists, and other skeptics doubt that conviction and coherence is what we need as opposed to tranquility and perspective. In the beginning of Vatsyayana’s commentary on the Nyaya Sutra, he argues:

When things are grasped through sources of knowledge (pramana), it is possible to act and succeed. Thus, sources of knowledge are useful (arthavat). Without sources of knowledge, there would be no successful action… Success is a relationship with its result: gaining or losing things, which could be happiness or sadness, or some way to or from either. The ends served by sources of knowledge are innumerable, since the living things who use sources of knowledge are themselves innumerable.

When things are grasped through sources of knowledge (pramana), it is possible to act and succeed. Thus, sources of knowledge are useful (arthavat). Without sources of knowledge, there would be no successful action… Success is a relationship with its result: gaining or losing things, which could be happiness or sadness, or some way to or from either. The ends served by sources of knowledge are innumerable, since the living things who use sources of knowledge are themselves innumerable.

When sources of knowledge are connected to things, so are the knower, known and knowledge. Why? Because without all of these knowledge of things is impossible. Of these, the person who acts with desire or fear is the knower, the way it is known is the source of knowledge, the known is the object, and truthful thought made the right way is knowledge. Truth is fully grasped when these four are in place.

So, what is truth? It is the grasping of being in something that is and not-being in something that isn’t. Grasping what is as what is, and what isn’t as what isn’t, is truth, as it is, unchanging.

How can something that isn’t be grasped through a knowledge source? At the time something that is is grasped, there is not grasping something that isn’t, like the light of a lamp that shows something that is and so also what isn’t. We think, if it was there, it would have been seen, but it wasn’t seen, so it isn’t there.

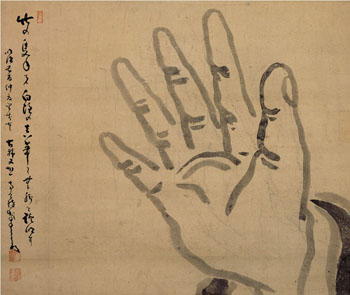

In Through The Looking Glass, Alice tells the White King she sees no one on the road, and the king praises her for having such eyes, seeing no one, and at such distance, which he can’t do. We can’t see no one, but we can look, and not see anyone, which can be said and understood as seeing no one. The play on words works in ancient India, Greece, China, and today in modern English. In Zen Buddhism, Hakuin painted blind men walking carefully on a log bridge several times, as the question had been asked, What does it look like to us that they are blind? What does it look like to see a rat in a maze, and know it can’t see the way out? Do you see it? Do you see and feel it? Do you see and feel and imagine it? You likely don’t talk it out much.

In Through The Looking Glass, Alice tells the White King she sees no one on the road, and the king praises her for having such eyes, seeing no one, and at such distance, which he can’t do. We can’t see no one, but we can look, and not see anyone, which can be said and understood as seeing no one. The play on words works in ancient India, Greece, China, and today in modern English. In Zen Buddhism, Hakuin painted blind men walking carefully on a log bridge several times, as the question had been asked, What does it look like to us that they are blind? What does it look like to see a rat in a maze, and know it can’t see the way out? Do you see it? Do you see and feel it? Do you see and feel and imagine it? You likely don’t talk it out much.

Uddyotakara, a later Nyaya logician, says in his commentary that all sources depend on perception, and sources of knowledge give us a true grasp of things, but there are fake sources of knowledge, and acting on a true source of knowledge leads to success, and acting on a fake source leads to failure. How does failure look, if not like a lack of success, another sort of seeing what you don’t see, or imagined, but did not perceive. The Nyaya Sutra and commentaries tell us that there are problems we can have with the four sources of knowledge, such that we can mis-perceive, and see what isn’t there, or not see what is there, such as unrecognized success or potential talent, even though perception is their primary source, that supports all others insofar as the others are justified.

Uddyotakara, a later Nyaya logician, says in his commentary that all sources depend on perception, and sources of knowledge give us a true grasp of things, but there are fake sources of knowledge, and acting on a true source of knowledge leads to success, and acting on a fake source leads to failure. How does failure look, if not like a lack of success, another sort of seeing what you don’t see, or imagined, but did not perceive. The Nyaya Sutra and commentaries tell us that there are problems we can have with the four sources of knowledge, such that we can mis-perceive, and see what isn’t there, or not see what is there, such as unrecognized success or potential talent, even though perception is their primary source, that supports all others insofar as the others are justified.

Perception is seeing or experiencing something for oneself, and can only be valid if it tells you something that doesn’t vary or change. Three examples of false perception given in the sutra are confusing smoke and dust, confusing a rope with a snake, and thinking that the hot earth is wet when in fact this is a mirage. There is a popular modern Indian novel about a man in a loveless arranged marriage who falls in love and has an affair with a prostitute called The Rope and The Snake. Vatsyayana says that some argue that for every thing there is a word and name that is based on conventional practices (vyavahara), and so perceptual thinking is verbal in nature, but this is a mistaken view, seeing words where they aren’t there, as we can look at an object without knowing its name, so perceptual understanding is not dependent on language. (10.11 – 20) His view is remarkably similar to Wittgenstein.

Perception is seeing or experiencing something for oneself, and can only be valid if it tells you something that doesn’t vary or change. Three examples of false perception given in the sutra are confusing smoke and dust, confusing a rope with a snake, and thinking that the hot earth is wet when in fact this is a mirage. There is a popular modern Indian novel about a man in a loveless arranged marriage who falls in love and has an affair with a prostitute called The Rope and The Snake. Vatsyayana says that some argue that for every thing there is a word and name that is based on conventional practices (vyavahara), and so perceptual thinking is verbal in nature, but this is a mistaken view, seeing words where they aren’t there, as we can look at an object without knowing its name, so perceptual understanding is not dependent on language. (10.11 – 20) His view is remarkably similar to Wittgenstein.

Vatsyayana argues that we can see what we think is smoke and infer there is fire, or hear that there is a fire by testimony, or make comparisons for ourselves from afar, but it is perception, seeing the fire, that is best and that best confirms comparisons, testimony and inferences. Giving a negative example, he similarly argues that seeing a mirage and hoping for water, it is only when we see what isn’t there, the water’s absence, that our inference is disproved. We can also make solid inferences, such as hearing thunder and inferring there was lightning, without making comparisons or hearing the testimony of others.

Vatsyayana argues that we can see what we think is smoke and infer there is fire, or hear that there is a fire by testimony, or make comparisons for ourselves from afar, but it is perception, seeing the fire, that is best and that best confirms comparisons, testimony and inferences. Giving a negative example, he similarly argues that seeing a mirage and hoping for water, it is only when we see what isn’t there, the water’s absence, that our inference is disproved. We can also make solid inferences, such as hearing thunder and inferring there was lightning, without making comparisons or hearing the testimony of others.

With knowledge, perception is best. When we learn something from trustworthy testimony, we may still want to know it another way, such as by inference. Understanding by inference, we may still want to know it through experience, but seeing it, the desire to know ceases, as in the example of fire above.

Vatsyayana explains comparison with the example that yak is like a cow, and this is sameness understood in terms of universals, classes of things with shared properties, such as having horns, or having four legs. Comparisons can be valid or invalid, depending on whether or not they are supported by inference, testimony, and of course, perception. Testimony, like perception and the rest, can be valid or not, as we all know from personal experience. Sometimes witnesses lie, and other times they are mistaken, either seeing what they couldn’t have, or not seeing what they could have. There is a psychology experiment that is somewhat well known where a video is shown to subjects of a line at a bank, a shot goes off, and everyone scatters, and some say they see a gun, some say the black guy in line had a gun, and there is no gun, showing racist bias, but also our ability to construct false memories, which can easily become false testimony.

Vatsyayana explains comparison with the example that yak is like a cow, and this is sameness understood in terms of universals, classes of things with shared properties, such as having horns, or having four legs. Comparisons can be valid or invalid, depending on whether or not they are supported by inference, testimony, and of course, perception. Testimony, like perception and the rest, can be valid or not, as we all know from personal experience. Sometimes witnesses lie, and other times they are mistaken, either seeing what they couldn’t have, or not seeing what they could have. There is a psychology experiment that is somewhat well known where a video is shown to subjects of a line at a bank, a shot goes off, and everyone scatters, and some say they see a gun, some say the black guy in line had a gun, and there is no gun, showing racist bias, but also our ability to construct false memories, which can easily become false testimony.

Vatsyayana says inference is the source that comes last, after experience involving perception, analogy and testimony. The Sutra says inference depends on previous perception and is of three types: from something prior, something later, and from something in common. Vatsyayana gives an example of each. If we see swollen storm clouds and infer it will rain, we infer from something prior, inferring an effect from a cause prior to it. If we see an overflowing river and infer it rained up stream, we infer from something later, inferring a cause from the effect later to it. If we infer that the sun was in one place and now another in the sky, we can infer that it moved, as a difference between the two.

Vatsyayana says inference is the source that comes last, after experience involving perception, analogy and testimony. The Sutra says inference depends on previous perception and is of three types: from something prior, something later, and from something in common. Vatsyayana gives an example of each. If we see swollen storm clouds and infer it will rain, we infer from something prior, inferring an effect from a cause prior to it. If we see an overflowing river and infer it rained up stream, we infer from something later, inferring a cause from the effect later to it. If we infer that the sun was in one place and now another in the sky, we can infer that it moved, as a difference between the two.

The Sutra says (1.1.41) that certainty is grasping something by thinking about possibilities, investigating thesis and counter-thesis, and that the sources can be objects of knowledge themselves, like a measuring scale. Vatsyayana adds that a scale can calibrate a second scale if we weigh gold with the first and then with the second, such that we know the second scale is off or not. Thus, we can use a tried and true knowledge source, like watching with our eyes, to test another knowledge source, like a theory we find in a text or the testimony of witnesses.

The Sutra says (1.1.41) that certainty is grasping something by thinking about possibilities, investigating thesis and counter-thesis, and that the sources can be objects of knowledge themselves, like a measuring scale. Vatsyayana adds that a scale can calibrate a second scale if we weigh gold with the first and then with the second, such that we know the second scale is off or not. Thus, we can use a tried and true knowledge source, like watching with our eyes, to test another knowledge source, like a theory we find in a text or the testimony of witnesses.

The Sutra says that critics (such as Jains and Buddhists, we imagine) could say this leads to an infinite regress, such that no source can be entirely established by other sources. Consider that the first scale could be off, which would mean we can’t use it to check against a second, but where do we know a scale is good without checking it against another? The answer for the Nyaya is that evidence is like the light of a lamp, self-evident in itself, leaning towards positive belief of what seems consistently true as establishing itself as true without controversy. The Nyaya Sutra says sometimes no further source is required, sometimes there is, and there is no fixed rule for determining this. (2.1.20) Because we, like Hindu Nyaya, seek freedom, discipline, pleasure and wealth in this proper descending order of importance, we proceed from what is to what we desire which isn’t.

The Sutra says that critics (such as Jains and Buddhists, we imagine) could say this leads to an infinite regress, such that no source can be entirely established by other sources. Consider that the first scale could be off, which would mean we can’t use it to check against a second, but where do we know a scale is good without checking it against another? The answer for the Nyaya is that evidence is like the light of a lamp, self-evident in itself, leaning towards positive belief of what seems consistently true as establishing itself as true without controversy. The Nyaya Sutra says sometimes no further source is required, sometimes there is, and there is no fixed rule for determining this. (2.1.20) Because we, like Hindu Nyaya, seek freedom, discipline, pleasure and wealth in this proper descending order of importance, we proceed from what is to what we desire which isn’t.

The Sutra says that opponents argue that objects are like dreams, mirages, or magic cities in the sky, not fixed as real, and says that they haven’t provided a reason to accept this. Vatsyayana says when we wake, we see with perception that the dreams weren’t real, which shows us perception and illusion are different. A Buddhist could object that they are making a comparison, a valid source of knowledge. The Nyaya would argue that perception is primary and more certain than comparison, such that physical objects are like mirages, but not entirely, as they are better established. But how can we say this without making a comparison to check, just as we are checking perception against comparison, with comparison, right now?

The Sutra says that opponents argue that objects are like dreams, mirages, or magic cities in the sky, not fixed as real, and says that they haven’t provided a reason to accept this. Vatsyayana says when we wake, we see with perception that the dreams weren’t real, which shows us perception and illusion are different. A Buddhist could object that they are making a comparison, a valid source of knowledge. The Nyaya would argue that perception is primary and more certain than comparison, such that physical objects are like mirages, but not entirely, as they are better established. But how can we say this without making a comparison to check, just as we are checking perception against comparison, with comparison, right now?

The Nyaya Sutra says that words are used to refer in three ways, to individuals, forms, and classes, and these multiple ways produce doubt, which sparks inquiry. (2.2.59) Vatsyayana provides us with the example of cow, and says the word refers to an individual cow, and anything shaped like a cow (to use the word metaphorically, as cow-ish-ness), and the class of all cows, which the Nyaya argue all have horns and four legs, like other classes of animals, forms of animals and individual animals. Vatsyayana says that the object of the word is thus determined by our ability to use it in these ways. The Sutra refutes those who think words refer to only one of these things, simply individuals, or simply forms, or simply classes, and says the meaning of a word is clearly all three of these uses. The Sutra uses the example of a clay cow, which has the form of a cow, and is included in classes such as things that have four feet, like a cow, but as Vatsyayana adds, if someone says to wash, bring or donate a cow, and we hand them a clay cow statue, we are wrong, and do not satisfy their requests, as it lacks the category of being alive, or an animal at that, so it is certainly the wrong sort of individual.

The Nyaya Sutra says that words are used to refer in three ways, to individuals, forms, and classes, and these multiple ways produce doubt, which sparks inquiry. (2.2.59) Vatsyayana provides us with the example of cow, and says the word refers to an individual cow, and anything shaped like a cow (to use the word metaphorically, as cow-ish-ness), and the class of all cows, which the Nyaya argue all have horns and four legs, like other classes of animals, forms of animals and individual animals. Vatsyayana says that the object of the word is thus determined by our ability to use it in these ways. The Sutra refutes those who think words refer to only one of these things, simply individuals, or simply forms, or simply classes, and says the meaning of a word is clearly all three of these uses. The Sutra uses the example of a clay cow, which has the form of a cow, and is included in classes such as things that have four feet, like a cow, but as Vatsyayana adds, if someone says to wash, bring or donate a cow, and we hand them a clay cow statue, we are wrong, and do not satisfy their requests, as it lacks the category of being alive, or an animal at that, so it is certainly the wrong sort of individual.

Debate manuals like the Nyaya Sutra of Gautama, the Organon of Aristotle and works by Moists in China were designed to introduce students and scholars to forms of argument, methods of attack and defense. Like Aristotle, Vatsyayana argues that debate proceeds from motives, and so a destructive skeptic debates destructively, without a committed motive or acceptable doctrine. Some have claimed that Aristotle’s syllogisms are deductively valid but Gautama’s syllogistic form of proof is not and based on induction. Actually, Aristotle has many syllogisms he openly admits in the text are not deductively valid on their own, and those forms, unlike the perfect four, weren’t studied by Islamic or Catholic logicians much. We can see induction and deduction working together in the syllogistic forms of both Aristotle and Gautama, and the similarities are quite striking. There are five formal steps to the Nyaya formal proof, but as Buddhists later perceived the first and second steps are identical to the fifth and the fourth, and can be eliminated.

Debate manuals like the Nyaya Sutra of Gautama, the Organon of Aristotle and works by Moists in China were designed to introduce students and scholars to forms of argument, methods of attack and defense. Like Aristotle, Vatsyayana argues that debate proceeds from motives, and so a destructive skeptic debates destructively, without a committed motive or acceptable doctrine. Some have claimed that Aristotle’s syllogisms are deductively valid but Gautama’s syllogistic form of proof is not and based on induction. Actually, Aristotle has many syllogisms he openly admits in the text are not deductively valid on their own, and those forms, unlike the perfect four, weren’t studied by Islamic or Catholic logicians much. We can see induction and deduction working together in the syllogistic forms of both Aristotle and Gautama, and the similarities are quite striking. There are five formal steps to the Nyaya formal proof, but as Buddhists later perceived the first and second steps are identical to the fifth and the fourth, and can be eliminated.

To make each form of proof easier to study, I take liberties with both the Indian and Greek syllogistic forms, preserving the information but changing the order it is presented to show how the information connects in sequence. Strangely, in the original texts of Aristotle, the most famous and basic form of syllogism is not If A then B, if B then C, so if A then C, as I present it, but rather In B then C, if A then B, so if A then C, such as Aristotle’s famous example, All men are mortal, Socrates is a man, so Socrates is (or rather, was) mortal. It does work, but it works better as Socrates is a man, all men are mortal, so Socrates is mortal.

To make each form of proof easier to study, I take liberties with both the Indian and Greek syllogistic forms, preserving the information but changing the order it is presented to show how the information connects in sequence. Strangely, in the original texts of Aristotle, the most famous and basic form of syllogism is not If A then B, if B then C, so if A then C, as I present it, but rather In B then C, if A then B, so if A then C, such as Aristotle’s famous example, All men are mortal, Socrates is a man, so Socrates is (or rather, was) mortal. It does work, but it works better as Socrates is a man, all men are mortal, so Socrates is mortal.

Similarly, Gautama’s central example is, Wherever there is smoke there is fire, as in a kitchen, so because there is smoke on the hill, there is fire on the hill. This is almost identical to Aristotle if we change the subjects to his, and say, Whoever is a man is moral, like Plato, so since Socrates is a man, Socrates is mortal. Thus, we can reorder Gautama’s proof in a similar A to B to C way, such that it reads, There is smoke on the hill, wherever there is smoke there is fire, as in a kitchen, so there is fire on the hill. Notice that this is not perfect, because perception of smoke is a central example of possible misperception, but it need not be, as smoke can look quite dissimilar from a dust cloud sometimes. The second example would then read, in line with Kanada’s cosmic observations, Sound is made, and whatever is made is impermanent, like a pot, so sound is impermanent. Those who say Gautama relies on induction focus on the addition of the extra example offered, and not on the clear similarities of the forms.

Similarly, Gautama’s central example is, Wherever there is smoke there is fire, as in a kitchen, so because there is smoke on the hill, there is fire on the hill. This is almost identical to Aristotle if we change the subjects to his, and say, Whoever is a man is moral, like Plato, so since Socrates is a man, Socrates is mortal. Thus, we can reorder Gautama’s proof in a similar A to B to C way, such that it reads, There is smoke on the hill, wherever there is smoke there is fire, as in a kitchen, so there is fire on the hill. Notice that this is not perfect, because perception of smoke is a central example of possible misperception, but it need not be, as smoke can look quite dissimilar from a dust cloud sometimes. The second example would then read, in line with Kanada’s cosmic observations, Sound is made, and whatever is made is impermanent, like a pot, so sound is impermanent. Those who say Gautama relies on induction focus on the addition of the extra example offered, and not on the clear similarities of the forms.

The Nyaya Sutra also lists fallacies, forms of mistakes in debate that sound solid but have flaws, much as the Nyaya say we could see a post in the dark and mistake it for a man. The Sutra warns us, much like Aristotle, that debate is about winning, but if we make arguments that are faulty, called clinchers by translators, cheap-shots, and if we point out faults that aren’t there in our opponent, called quibbles, nit-picking, we risk losing the debate if anyone notices, and we shouldn’t make them in the first place if we want to not only win, but be right.

The Nyaya Sutra also lists fallacies, forms of mistakes in debate that sound solid but have flaws, much as the Nyaya say we could see a post in the dark and mistake it for a man. The Sutra warns us, much like Aristotle, that debate is about winning, but if we make arguments that are faulty, called clinchers by translators, cheap-shots, and if we point out faults that aren’t there in our opponent, called quibbles, nit-picking, we risk losing the debate if anyone notices, and we shouldn’t make them in the first place if we want to not only win, but be right.

For fallacies, the Sutra includes silence (which would lose a debate indeed), changing the thesis, contradicting the thesis, evasion (in one commentary, it is translated, I am called by nature… and then, we hear screeching tires outside), meaningless or incoherent speech (Chomsky gave the example for linguistics of Colorless sleep furiously green, which he thinks is meaningless), repetition (rather than additional argument where it is needed), overlooking the fallacies in an opponent’s argument (which could be pointed out by others), and my personal favorite, sharing the fault, pointing out a fault in an opponent that is also a fault in one’s own argument, or a fault in everyone (such as, My opponent is putting forward a mere mortal point of view).

For fallacies, the Sutra includes silence (which would lose a debate indeed), changing the thesis, contradicting the thesis, evasion (in one commentary, it is translated, I am called by nature… and then, we hear screeching tires outside), meaningless or incoherent speech (Chomsky gave the example for linguistics of Colorless sleep furiously green, which he thinks is meaningless), repetition (rather than additional argument where it is needed), overlooking the fallacies in an opponent’s argument (which could be pointed out by others), and my personal favorite, sharing the fault, pointing out a fault in an opponent that is also a fault in one’s own argument, or a fault in everyone (such as, My opponent is putting forward a mere mortal point of view).

The Sutra gives three types of quibbling, which correspond to the three uses of words, thing, form and class. Vatsyayana give us examples for each, as he does with his commentary for everything in the Sutra. For quibbling over words used for things, he says someone could say they had a new (nava) blanket, and someone else could misunderstand the individual word and think they claimed they had nine (also nava) blankets, and point out the false fallacy. For quibbling over form, someone could say, The stands cry out, and someone could foolishly say that stands can’t cry, as they don’t have feelings, but they are wrong. I have mistaken this for scaffolds, and thus the hangman rather than parade crowds, due to an earlier translation. For quibbling over class, someone could say, All Brahmins are educated, possibly to construct an example of a Nyaya syllogism for your assignment, and someone else could wrongly object, Not all Brahmins are educated, because some are only three years old, and just learning to talk!

The Sutra gives three types of quibbling, which correspond to the three uses of words, thing, form and class. Vatsyayana give us examples for each, as he does with his commentary for everything in the Sutra. For quibbling over words used for things, he says someone could say they had a new (nava) blanket, and someone else could misunderstand the individual word and think they claimed they had nine (also nava) blankets, and point out the false fallacy. For quibbling over form, someone could say, The stands cry out, and someone could foolishly say that stands can’t cry, as they don’t have feelings, but they are wrong. I have mistaken this for scaffolds, and thus the hangman rather than parade crowds, due to an earlier translation. For quibbling over class, someone could say, All Brahmins are educated, possibly to construct an example of a Nyaya syllogism for your assignment, and someone else could wrongly object, Not all Brahmins are educated, because some are only three years old, and just learning to talk!

Third Assignment: 1) Give an example of each of the Jain skeptical principles, like the blind men and elephant but not that, and explain your example. 2) Give an example of Gautama’s syllogistic form of proof, and explain your example. 3) Give an example of sharing the fault and the three types of quibbling of the Nyaya Sutra, and explain your examples.

Leave a comment