Aristotle is one of the most famous logicians in history, whom many would call the father of logic itself, but Aristotle, like Kanada of India, was not primarily interested in logic or debate, but rather what we can say about the cosmos and human mind, which includes what can or can’t be argued successfully about it. Followers of Aristotle, possibly including Andronicus of Rhodes, collected the six works Aristotle wrote about definition and debate, his Categories, On Interpretation, Prior Analytics, Posterior Analytics, Topics and Sophistical Refutations, which may have been public texts or private sets of notes for his students, into a work known as the Organon around 40 BCE, 300 years after Aristotle started his talks and walks around the Lyceum. We will cover some of the central ideas of his Organon, including the four perfect forms of the syllogism, and what Christian theologians such as Boethius called the Square of Opposition.

Aristotle is one of the most famous logicians in history, whom many would call the father of logic itself, but Aristotle, like Kanada of India, was not primarily interested in logic or debate, but rather what we can say about the cosmos and human mind, which includes what can or can’t be argued successfully about it. Followers of Aristotle, possibly including Andronicus of Rhodes, collected the six works Aristotle wrote about definition and debate, his Categories, On Interpretation, Prior Analytics, Posterior Analytics, Topics and Sophistical Refutations, which may have been public texts or private sets of notes for his students, into a work known as the Organon around 40 BCE, 300 years after Aristotle started his talks and walks around the Lyceum. We will cover some of the central ideas of his Organon, including the four perfect forms of the syllogism, and what Christian theologians such as Boethius called the Square of Opposition.

In the Categories Aristotle assumes that things have purposes according to their natures, and these purposes correspond to concepts that can be put into words. Aristotle believes that we must observe nature and say what can be said of things, based on their similarities and differences. For example, Aristotle says that ‘animal’ can be said or predicated of both a man and an ox, just as ‘man’ and ‘animal’ can be predicated of any human male individual. A Genera or Genus is the family to which a thing belongs. This is paired with Species, the subgroup of the family. He says that if you are giving an account of a particular tree, you would say more with the species of tree than you would of the genus ‘plant’.

In the Categories Aristotle assumes that things have purposes according to their natures, and these purposes correspond to concepts that can be put into words. Aristotle believes that we must observe nature and say what can be said of things, based on their similarities and differences. For example, Aristotle says that ‘animal’ can be said or predicated of both a man and an ox, just as ‘man’ and ‘animal’ can be predicated of any human male individual. A Genera or Genus is the family to which a thing belongs. This is paired with Species, the subgroup of the family. He says that if you are giving an account of a particular tree, you would say more with the species of tree than you would of the genus ‘plant’.

Aristotle says there are ten categories which he says apply to things that are separate and in no way composite, made of each other, but there are several of these such as relation, place, time, position, state, and affection are all quite confusingly interrelated. Aristotle gives us the categories from above, with substance as primary, down past the others to passion below, from high to low. In reverse order, working upward, Aristotle’s ten categories are passion, action, state, position, time, place, relation (or relatives), quality, quantity, and substance. This charts the order of events and characters in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, working from inclusive passion, being acted-upon, to exclusive substance, things that are identical to themselves and nothing else.

Aristotle says there are ten categories which he says apply to things that are separate and in no way composite, made of each other, but there are several of these such as relation, place, time, position, state, and affection are all quite confusingly interrelated. Aristotle gives us the categories from above, with substance as primary, down past the others to passion below, from high to low. In reverse order, working upward, Aristotle’s ten categories are passion, action, state, position, time, place, relation (or relatives), quality, quantity, and substance. This charts the order of events and characters in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, working from inclusive passion, being acted-upon, to exclusive substance, things that are identical to themselves and nothing else.

First, the White Rabbit is passion, who acts on Alice, moved by her passion without thinking into chasing after the rabbit. Second, after the banquet hall, where Alice can’t act but is moved by her tears, the mouse is action, as Alice acts on the mouse who flees her passionate talk of her cat, acted-upon but negatively, opposite the way the White Rabbit positively acted-upon Alice. Third, there is the bird’s caucus race, which mocks politics, also known as the state. Fourth, the White Rabbit mistakes Alice for his servant, and Alice takes on the servant’s position, ultimately finding herself in quite the imposition, filling the White Rabbit’s entire house. Fifth, the Caterpillar is time, who takes away the certainty of all things, and includes all changes and possibilities as indeterminate. Sixth, the Cheshire cat is space, who shows Alice conflicting positions, each exclusive and opposed to the other.

First, the White Rabbit is passion, who acts on Alice, moved by her passion without thinking into chasing after the rabbit. Second, after the banquet hall, where Alice can’t act but is moved by her tears, the mouse is action, as Alice acts on the mouse who flees her passionate talk of her cat, acted-upon but negatively, opposite the way the White Rabbit positively acted-upon Alice. Third, there is the bird’s caucus race, which mocks politics, also known as the state. Fourth, the White Rabbit mistakes Alice for his servant, and Alice takes on the servant’s position, ultimately finding herself in quite the imposition, filling the White Rabbit’s entire house. Fifth, the Caterpillar is time, who takes away the certainty of all things, and includes all changes and possibilities as indeterminate. Sixth, the Cheshire cat is space, who shows Alice conflicting positions, each exclusive and opposed to the other.

Seventh, the Duchess and baby are relatives or relations, and Alice moves from taking the position outside the pigeon defending the egg in her next, to the cat who watches the Duchess beat her baby, to Alice dropping the baby when it turns into a pig, as the cat thought it would. Eighth, the Mad Tea Party is quality, with the Hatter and Hare insane, of bad mind, and the Hare insisting he used the best butter to fix the pocket watch, which is terrible. Ninth, the Queen of Heart’s garden is quantity, with the two, five and seven cards forming an addition problem and the Queen threatening everyone with subtraction. Tenth and finally, the King of Heart’s trial is substance, or lack thereof, just as the Tea Party lacked quality, with the tarts as a substance stolen and returned, the jury and king incapable of coming to substantive, proof-worthy judgements, and Alice declaring everything to be an empty pack of cards, devoid of substance and meaning.

Seventh, the Duchess and baby are relatives or relations, and Alice moves from taking the position outside the pigeon defending the egg in her next, to the cat who watches the Duchess beat her baby, to Alice dropping the baby when it turns into a pig, as the cat thought it would. Eighth, the Mad Tea Party is quality, with the Hatter and Hare insane, of bad mind, and the Hare insisting he used the best butter to fix the pocket watch, which is terrible. Ninth, the Queen of Heart’s garden is quantity, with the two, five and seven cards forming an addition problem and the Queen threatening everyone with subtraction. Tenth and finally, the King of Heart’s trial is substance, or lack thereof, just as the Tea Party lacked quality, with the tarts as a substance stolen and returned, the jury and king incapable of coming to substantive, proof-worthy judgements, and Alice declaring everything to be an empty pack of cards, devoid of substance and meaning.

Aristotle writes, “The distinctive mark of substance is that it can admit contrary qualities. Thus, a color cannot be both white and black, nor can the same act be good and bad: this is true for any non substance, but substances can at different times be white and black…The same individual person is at one time white, at another black, at one time warm, at another cold, at one time good, at another bad.” Note that by “white” Aristotle means a sick, pale or elderly person, not a judgement about ethnicity. Aristotle says the proposition “He is sitting,” can be true, then false, then true as a person sits, stands, and then sits again. Aristotle denies that things can possess contrary qualities (be both white and black) or be in contrary states (good and evil) at the same time. The old joke about a newspaper being black and white and red all over says otherwise. Aristotle considers time, but does not consider that part of a person can be white, or pale, or sick, and another part not, like having great eyesight and a sore throat.

Aristotle writes, “The distinctive mark of substance is that it can admit contrary qualities. Thus, a color cannot be both white and black, nor can the same act be good and bad: this is true for any non substance, but substances can at different times be white and black…The same individual person is at one time white, at another black, at one time warm, at another cold, at one time good, at another bad.” Note that by “white” Aristotle means a sick, pale or elderly person, not a judgement about ethnicity. Aristotle says the proposition “He is sitting,” can be true, then false, then true as a person sits, stands, and then sits again. Aristotle denies that things can possess contrary qualities (be both white and black) or be in contrary states (good and evil) at the same time. The old joke about a newspaper being black and white and red all over says otherwise. Aristotle considers time, but does not consider that part of a person can be white, or pale, or sick, and another part not, like having great eyesight and a sore throat.

Heraclitus, an opponent that Plato and Aristotle argue against, thought that things were good and bad by perspective and positioning and so things can have contrary qualities and be in contrary states at the same time, and even in the same place. Aristotle completely denies the possibility of this, saying “If, then, someone says that statements and opinions are capable of admitting contrary qualities, his contention is unsound”. In his On Interpretation, Aristotle says that we must limit our discussion to propositions that are true or false exclusively. He argues that prayers, promises and requests are neither true nor false because they do not guarantee whether they will be fulfilled or not. An affirmation is a positive statement of something, a denial a negative statement. Thus, “I exist” is a positive affirmation, as is “This apple is red”, whereas ‘I do not exist’ or ‘I doubt that I exist’ are negative denials, as is “This apple is not red”.

Heraclitus, an opponent that Plato and Aristotle argue against, thought that things were good and bad by perspective and positioning and so things can have contrary qualities and be in contrary states at the same time, and even in the same place. Aristotle completely denies the possibility of this, saying “If, then, someone says that statements and opinions are capable of admitting contrary qualities, his contention is unsound”. In his On Interpretation, Aristotle says that we must limit our discussion to propositions that are true or false exclusively. He argues that prayers, promises and requests are neither true nor false because they do not guarantee whether they will be fulfilled or not. An affirmation is a positive statement of something, a denial a negative statement. Thus, “I exist” is a positive affirmation, as is “This apple is red”, whereas ‘I do not exist’ or ‘I doubt that I exist’ are negative denials, as is “This apple is not red”.

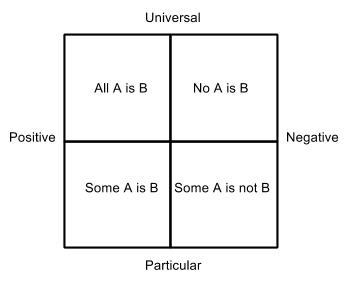

Aristotle says there are also universal and particular statements, which corresponds to fixed, unchanging properties in things, particularly the forces above the lunar sphere and imperfect, changing properties and forms below. All people are good and No people are good are universal propositions, and Some people are good and Some people are not good are particular propositions. Notice that All people are not good and No people are good are equivalent and exchangeable, as are Not all people are good and Some people are not good. The Square of Opposition traditionally puts universal on top, particular on the bottom, down with us mortals, positive affirmation on the left and negative denial on the right, such that the top left positive universal corner is All people are good (All A is B), the top right negative universal corner is No people are good, the bottom left positive particular corner is Some people are good, and the bottom right negative particular corner is Some people are not good.

Aristotle says there are also universal and particular statements, which corresponds to fixed, unchanging properties in things, particularly the forces above the lunar sphere and imperfect, changing properties and forms below. All people are good and No people are good are universal propositions, and Some people are good and Some people are not good are particular propositions. Notice that All people are not good and No people are good are equivalent and exchangeable, as are Not all people are good and Some people are not good. The Square of Opposition traditionally puts universal on top, particular on the bottom, down with us mortals, positive affirmation on the left and negative denial on the right, such that the top left positive universal corner is All people are good (All A is B), the top right negative universal corner is No people are good, the bottom left positive particular corner is Some people are good, and the bottom right negative particular corner is Some people are not good.

Sometimes Aristotle’s absolute statements are called generals, and sometimes universals, which is a problem, as we use the word general in a relative way, and the term universal in an absolute way, much like how the conjunction AND can be more inclusive and loose or exclusive and strict, requiring every last part to be included together. We can say that generally oxen have four legs, but if there is one or more oxen that don’t we can’t say that oxen universally have four legs. Aristotle would probably say that an oxen that doesn’t have four legs is not a full, healthy oxen, and using the term universal is more what he meant, arguing against Heraclitus that we can’t have some and some when it comes to fundamental categories such as four legged animals or oxen.

Sometimes Aristotle’s absolute statements are called generals, and sometimes universals, which is a problem, as we use the word general in a relative way, and the term universal in an absolute way, much like how the conjunction AND can be more inclusive and loose or exclusive and strict, requiring every last part to be included together. We can say that generally oxen have four legs, but if there is one or more oxen that don’t we can’t say that oxen universally have four legs. Aristotle would probably say that an oxen that doesn’t have four legs is not a full, healthy oxen, and using the term universal is more what he meant, arguing against Heraclitus that we can’t have some and some when it comes to fundamental categories such as four legged animals or oxen.

Aristotle says that the statements on what we can see as opposite corners of the Square of Opposition cannot both be true at the same time, such that All A is B and Some A is not B cannot both be true, contradicting each other, and No A is B and Some A is B cannot either. He also says that either the particular positive or particular negative must be true, such that either Some A is B or Some A is not B, but this is only true, as later logicians noted in commentaries on Aristotle, if there are some As to begin with. If there are no unicorns, then neither Some unicorns are good nor Some unicorns are not good need be true. Also, if unicorns exist, but are relatively good and not good, both and neither as Heraclitus or Nagarjuna would say, then not only both particulars, but all four corners are true, as all and some unicorns are good and not good.

Aristotle says that the statements on what we can see as opposite corners of the Square of Opposition cannot both be true at the same time, such that All A is B and Some A is not B cannot both be true, contradicting each other, and No A is B and Some A is B cannot either. He also says that either the particular positive or particular negative must be true, such that either Some A is B or Some A is not B, but this is only true, as later logicians noted in commentaries on Aristotle, if there are some As to begin with. If there are no unicorns, then neither Some unicorns are good nor Some unicorns are not good need be true. Also, if unicorns exist, but are relatively good and not good, both and neither as Heraclitus or Nagarjuna would say, then not only both particulars, but all four corners are true, as all and some unicorns are good and not good.

Aristotle notices a problem with the categories of good and not-good, because not-good and bad are two different things if neutral, neither good nor bad, counts as not-good. We hear “not good” both ways, likely depending on time and place. Does A is good contradict A is bad or A is not good more? Confusingly, Aristotle says that neutrality is opposed to both good and bad, as it is neither, and tries to solve the problem by saying that if A is good, it seems more contrary, relatively speaking, to say A is not good than it is to say A is bad, which seems off. If I politely say A is not good, rather than say A is bad, and I am wrong either way, because A is actually good, I don’t know why the softer, safer statement is more wrong, especially if this threatens to make our reasoning unsound according to Aristotle’s earlier claims about categoricals.

Aristotle notices a problem with the categories of good and not-good, because not-good and bad are two different things if neutral, neither good nor bad, counts as not-good. We hear “not good” both ways, likely depending on time and place. Does A is good contradict A is bad or A is not good more? Confusingly, Aristotle says that neutrality is opposed to both good and bad, as it is neither, and tries to solve the problem by saying that if A is good, it seems more contrary, relatively speaking, to say A is not good than it is to say A is bad, which seems off. If I politely say A is not good, rather than say A is bad, and I am wrong either way, because A is actually good, I don’t know why the softer, safer statement is more wrong, especially if this threatens to make our reasoning unsound according to Aristotle’s earlier claims about categoricals.

Much like the two ways we use OR inclusively and exclusively, such that we can have more than one or only one choice, both or either the bottom particular corners of the Square can be true, such that if Some A is B, it is possible that Some A is not B, but not necessary, like inclusive OR, but only one or the other, but necessarily one, of the top universal corners of the Square While all and none are absolute and exclusive, like polar black and white, some and some not are relative and inclusive shades of grey. Aristotle presents us with dozens of forms of argument called syllogisms that can be used in debate, but only the first four “perfect” forms, as others after Aristotle call them, require no additional information to be valid, as Aristotle himself tells us, so it is these four forms that the followers of Aristotle recreated for centuries. There is a syllogism with two premises and a conclusion for each corner of the Square of Opposition, and the conclusion of each is the statement of each corner. We take the medieval names for the four, which are Barbara, Celarent, Darii and Ferio, one for each of the first four consonants of the Latin alphabet.

Much like the two ways we use OR inclusively and exclusively, such that we can have more than one or only one choice, both or either the bottom particular corners of the Square can be true, such that if Some A is B, it is possible that Some A is not B, but not necessary, like inclusive OR, but only one or the other, but necessarily one, of the top universal corners of the Square While all and none are absolute and exclusive, like polar black and white, some and some not are relative and inclusive shades of grey. Aristotle presents us with dozens of forms of argument called syllogisms that can be used in debate, but only the first four “perfect” forms, as others after Aristotle call them, require no additional information to be valid, as Aristotle himself tells us, so it is these four forms that the followers of Aristotle recreated for centuries. There is a syllogism with two premises and a conclusion for each corner of the Square of Opposition, and the conclusion of each is the statement of each corner. We take the medieval names for the four, which are Barbara, Celarent, Darii and Ferio, one for each of the first four consonants of the Latin alphabet.

BARBARA, the Positive Universal Syllogism:

BARBARA, the Positive Universal Syllogism:

If All A are B, and All B are C, then All A are C.

If all humans are animals, and all animals are alive, then all humans are alive.

In the Venn diagram form, if a circle A is entirely within a circle B, and this circle B is entirely in a third circle C, then circle A must be entirely inside circle C.

CELARENT, the Negative Universal Syllogism:

CELARENT, the Negative Universal Syllogism:

If All A are B, and No B are C, then No A are C.

If all humans are animals, and no animals are made of stone, then no humans are stone.

As a Venn diagram, if A is entirely within B, and no B is inside C, then no A can be inside C.

DARII, the Positive Particular Syllogism:

DARII, the Positive Particular Syllogism:

If Some A are B, and All B are C, then Some A are C.

If some animals are humans, and all humans are funny, then some animals are funny.

As a Venn diagram, if some A is inside B and all B is inside C then some A must be inside C.

FERIO, the Negative Particular Syllogism:

FERIO, the Negative Particular Syllogism:

If Some A are B, and No B are C, then Some A are not C.

If some animals are humans, and no humans are reptiles, then some animals are not reptiles.

As a Venn diagram, if some A is in B and no B is in C then some of A is outside C.

In Lewis Carroll’s Through The Looking Glass, the second of Alice’s adventures, the Red Queen, Red King, White Queen and White King are the four forms of the syllogism, and the four corresponding corners of the Square of Opposition. The White Queen, inclusively open like a child, is the universal positive (All, All, All), the Red Queen is the universal negative (All, None, None), the White King is the particular positive (Some, All, Some) and the Red King is the particular negative (Some, None, Some-Not). If all things are possible to think if you Shut your eyes and try very hard, as the White Queen suggests to Alice, and if all impossible things are things indeed, even if they, unicorns and we are all quite mental, then Alice can think six or more impossible things before breakfast if she shuts her eyes, imagines, and tries very hard, as the White Queen implies but doesn’t say directly, meaning what she doesn’t say syllogistically. If All ways are mine, as the Red Queen says, and None of what’s mine is yours, as the Duchess moralizes, then none of these ways are yours, is what the Red Queen means but doesn’t say, which we understand and infer quite syllogistically from what is given in her words.

In Lewis Carroll’s Through The Looking Glass, the second of Alice’s adventures, the Red Queen, Red King, White Queen and White King are the four forms of the syllogism, and the four corresponding corners of the Square of Opposition. The White Queen, inclusively open like a child, is the universal positive (All, All, All), the Red Queen is the universal negative (All, None, None), the White King is the particular positive (Some, All, Some) and the Red King is the particular negative (Some, None, Some-Not). If all things are possible to think if you Shut your eyes and try very hard, as the White Queen suggests to Alice, and if all impossible things are things indeed, even if they, unicorns and we are all quite mental, then Alice can think six or more impossible things before breakfast if she shuts her eyes, imagines, and tries very hard, as the White Queen implies but doesn’t say directly, meaning what she doesn’t say syllogistically. If All ways are mine, as the Red Queen says, and None of what’s mine is yours, as the Duchess moralizes, then none of these ways are yours, is what the Red Queen means but doesn’t say, which we understand and infer quite syllogistically from what is given in her words.

If the White King says he sent almost all his horses along with his men, but not two of them who are needed in the game later, and if Alice has met all the thousands that were sent, 4,207 precisely who pass Alice on her way, then Alice has met some but not all of the horses, namely the Red and White Knights who stand between Alice and the final square where she becomes a queen. If all things are dreams, as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee tell Alice, and some dreams are untrue or not ours alone, then all things are somewhat untrue, and somewhat aren’t ours alone, which is what Tweedle Dum, Dee and the Red King dreaming silently imply, but don’t say. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and no B is C then some of A is C. As Aristotle says, if we have only some and no all or none, we can’t draw syllogistic judgements completely, leaving us with only a relative, somewhat satisfying conclusion, just as the Red King silently dreams and says nothing to Alice after she happily dances around hand in hand with both twin brothers.

If the White King says he sent almost all his horses along with his men, but not two of them who are needed in the game later, and if Alice has met all the thousands that were sent, 4,207 precisely who pass Alice on her way, then Alice has met some but not all of the horses, namely the Red and White Knights who stand between Alice and the final square where she becomes a queen. If all things are dreams, as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee tell Alice, and some dreams are untrue or not ours alone, then all things are somewhat untrue, and somewhat aren’t ours alone, which is what Tweedle Dum, Dee and the Red King dreaming silently imply, but don’t say. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and no B is C then some of A is C. As Aristotle says, if we have only some and no all or none, we can’t draw syllogistic judgements completely, leaving us with only a relative, somewhat satisfying conclusion, just as the Red King silently dreams and says nothing to Alice after she happily dances around hand in hand with both twin brothers.

Aristotle argued we can derive true knowledge from chaining these forms together. He argues in the text that since the Scythians have no vines, they thus no grapes, no intoxication, and thus no flute players. Aristotle, like Plato in the Symposium, associates intoxication with flutes, like associating saxophones and scotch on the rocks. He gives another example. If something is metal, then it will cut, and since hatchets are made of metal, therefore hatchets will cut. In the 1600s, Sir Francis Bacon rejected the syllogism as fallible, just as Islamic scholars and scientists had before, arguing that they were too limited for doing varied and fine distinctions in science. Consider that all metal things do not cut, nor do all knives, the butter knife being an example of something metal and a knife that does not cut, created by a French nobleman to prevent his dinner guests from picking their teeth.

Aristotle argued we can derive true knowledge from chaining these forms together. He argues in the text that since the Scythians have no vines, they thus no grapes, no intoxication, and thus no flute players. Aristotle, like Plato in the Symposium, associates intoxication with flutes, like associating saxophones and scotch on the rocks. He gives another example. If something is metal, then it will cut, and since hatchets are made of metal, therefore hatchets will cut. In the 1600s, Sir Francis Bacon rejected the syllogism as fallible, just as Islamic scholars and scientists had before, arguing that they were too limited for doing varied and fine distinctions in science. Consider that all metal things do not cut, nor do all knives, the butter knife being an example of something metal and a knife that does not cut, created by a French nobleman to prevent his dinner guests from picking their teeth.

Aristotle states that, as we can see with the Ferio Venn diagram, if we only have some, some and some statements, we can’t draw conclusions at all. Aristotle sometimes goes back on his earlier statements and gives us examples when things that are normally universal and certain can be conditional, can be different in certain situations and circumstances. He says that it is never right to kill your father, but among the Triballi tribe, the gods sometimes demand it. Since the gods are one’s super-parents and one’s obligations to them supersedes one’s obligations to one’s parents, he says that the Triballi rightly sacrifice their fathers. Notice that Aristotle believes that the polytheistic gods are real and that human sacrifice is sometimes quite logical and rational. He also states in his other work that all crows are black and all swans are white, but unfortunately for Aristotle both white crows and black swans thrive in Australia.

Aristotle states that, as we can see with the Ferio Venn diagram, if we only have some, some and some statements, we can’t draw conclusions at all. Aristotle sometimes goes back on his earlier statements and gives us examples when things that are normally universal and certain can be conditional, can be different in certain situations and circumstances. He says that it is never right to kill your father, but among the Triballi tribe, the gods sometimes demand it. Since the gods are one’s super-parents and one’s obligations to them supersedes one’s obligations to one’s parents, he says that the Triballi rightly sacrifice their fathers. Notice that Aristotle believes that the polytheistic gods are real and that human sacrifice is sometimes quite logical and rational. He also states in his other work that all crows are black and all swans are white, but unfortunately for Aristotle both white crows and black swans thrive in Australia.

Aristotle also provides us with defenses against syllogisms, to defend against presumably good arguments, but on the side that doesn’t seem to be certainly true. He says that in order to avoid having a syllogism drawn against one’s own argument, one should not let the opponent give the same term twice over. If one’s opponent argues that A is B, and B is C, therefore A is C, one should attack the twice used middle term (the B that links A and C in the syllogisms) to prevent an argument from reaching a conclusion. For example, if one’s opponent argues war is American, what is American is good, therefore war is good, one should argue that the war is only somewhat American, that only some of America is involved in war, or that only some of America is good because America is being used to link war to the good. It seems that we naturally know to do this in arguing, just like using the forms, long before we take a logic class or read Aristotle. If we want to destroy a position, we show that it is relative, not absolute.

Aristotle also provides us with defenses against syllogisms, to defend against presumably good arguments, but on the side that doesn’t seem to be certainly true. He says that in order to avoid having a syllogism drawn against one’s own argument, one should not let the opponent give the same term twice over. If one’s opponent argues that A is B, and B is C, therefore A is C, one should attack the twice used middle term (the B that links A and C in the syllogisms) to prevent an argument from reaching a conclusion. For example, if one’s opponent argues war is American, what is American is good, therefore war is good, one should argue that the war is only somewhat American, that only some of America is involved in war, or that only some of America is good because America is being used to link war to the good. It seems that we naturally know to do this in arguing, just like using the forms, long before we take a logic class or read Aristotle. If we want to destroy a position, we show that it is relative, not absolute.

In Aristotle’s Sophistical Refutations, he lists fallacies that are common errors in argument beyond mistakes made in chaining syllogisms and forms together, much as Gautama does in the Nyaya Sutra. The Fallacy of Equivocation is confusing a word that means one thing with meaning another. Many today use the classic Who’s on first routine to illustrate, with Who as the name of the player on first, so the question, Who’s on first? could be answered Who is, or Yes. The Fallacy of Amphibology is confusing a sentence that means one thing with meaning another, like equivocation, but for whole statements. If I say you can have one car or another, and you wrongly interpret my or to be inclusive, such that you can have more than one, I could accuse you of amphibology, as the sentence can be understood in more than one way. Notice that equivocation and amphibology is a mistake we can make in interpreting others, but also in interpreting ourselves, such that we are changing the thesis, as the Nyaya would say.

In Aristotle’s Sophistical Refutations, he lists fallacies that are common errors in argument beyond mistakes made in chaining syllogisms and forms together, much as Gautama does in the Nyaya Sutra. The Fallacy of Equivocation is confusing a word that means one thing with meaning another. Many today use the classic Who’s on first routine to illustrate, with Who as the name of the player on first, so the question, Who’s on first? could be answered Who is, or Yes. The Fallacy of Amphibology is confusing a sentence that means one thing with meaning another, like equivocation, but for whole statements. If I say you can have one car or another, and you wrongly interpret my or to be inclusive, such that you can have more than one, I could accuse you of amphibology, as the sentence can be understood in more than one way. Notice that equivocation and amphibology is a mistake we can make in interpreting others, but also in interpreting ourselves, such that we are changing the thesis, as the Nyaya would say.

There are several fallacies Aristotle lists that seem sorts of amphibology. The Fallacy of Accent seems to be a sort of amphibology, understanding a sentence wrongly based on what word is accented, but Aristotle lists it separately. Many have noted that we hear sentences quite differently based on which word is accented, which we can see if we say the sentence I think that she should have got the job with the accent on each word, one at a time (Consider: I think that she SHOULD have got the job, versus I think that SHE should have got the job). There is also the Fallacy of Figure of Speech, which the Nyaya list also, misunderstanding a metaphor, which also seems a sort of amphibology, or at least equivocation, depending on how many words are used.

There are several fallacies Aristotle lists that seem sorts of amphibology. The Fallacy of Accent seems to be a sort of amphibology, understanding a sentence wrongly based on what word is accented, but Aristotle lists it separately. Many have noted that we hear sentences quite differently based on which word is accented, which we can see if we say the sentence I think that she should have got the job with the accent on each word, one at a time (Consider: I think that she SHOULD have got the job, versus I think that SHE should have got the job). There is also the Fallacy of Figure of Speech, which the Nyaya list also, misunderstanding a metaphor, which also seems a sort of amphibology, or at least equivocation, depending on how many words are used.

The Fallacy of Composition is wrongly attributing the property of a part to a greater whole. For example, “If water is wet, and humans are three fifths water, then humans are wet”, or “If San Francisco is progressive, then all of California is progressive”. The converse Fallacy of Division is wrongly attributing the property of the greater whole to a particular part, the fallacy of composition in reverse. For example, “If water is wet, and water has two hydrogen molecules, then hydrogen is wet”, or “If San Francisco is progressive, then my conservative uncle who lives there must be progressive”. Bigotry and prejudice are types of fallacious composition and division. If I say, “He is a Hindu, and he is a jerk, so all Hindus are jerks”, I have committed the fallacy of composition, judging the group by what is thought of the individual. Likewise, if I say, “All atheists are immoral, and she is an atheist, so she is immoral”, I have committed the fallacy of division, judging the individual by what is thought of the group.

The Fallacy of Composition is wrongly attributing the property of a part to a greater whole. For example, “If water is wet, and humans are three fifths water, then humans are wet”, or “If San Francisco is progressive, then all of California is progressive”. The converse Fallacy of Division is wrongly attributing the property of the greater whole to a particular part, the fallacy of composition in reverse. For example, “If water is wet, and water has two hydrogen molecules, then hydrogen is wet”, or “If San Francisco is progressive, then my conservative uncle who lives there must be progressive”. Bigotry and prejudice are types of fallacious composition and division. If I say, “He is a Hindu, and he is a jerk, so all Hindus are jerks”, I have committed the fallacy of composition, judging the group by what is thought of the individual. Likewise, if I say, “All atheists are immoral, and she is an atheist, so she is immoral”, I have committed the fallacy of division, judging the individual by what is thought of the group.

There are several fallacies that mistake the structure of the argument as a whole, beyond mistaking the word or the statement. There is the Fallacy of Irrelevant Conclusion, missing the point, also known as a red herring. There is the Fallacy of Begging the Question, which similarly is stating something questionable, but saying something that requires further evidence rather than stating something that isn’t important. The Fallacy of False Cause is misunderstanding something prior as cause when it isn’t, such as thinking the moon causes people to go to sleep. Conversely, there is the Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent, assuming something prior is a cause when it isn’t, but it often is, such as thinking that if drugs can make people crazy, then all crazy people must be on drugs.

There are several fallacies that mistake the structure of the argument as a whole, beyond mistaking the word or the statement. There is the Fallacy of Irrelevant Conclusion, missing the point, also known as a red herring. There is the Fallacy of Begging the Question, which similarly is stating something questionable, but saying something that requires further evidence rather than stating something that isn’t important. The Fallacy of False Cause is misunderstanding something prior as cause when it isn’t, such as thinking the moon causes people to go to sleep. Conversely, there is the Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent, assuming something prior is a cause when it isn’t, but it often is, such as thinking that if drugs can make people crazy, then all crazy people must be on drugs.

Finally, there is the Fallacy of the Multiple Question, asking a question that suggests things that either haven’t been stated or aren’t true, also known as a leading question. The famous unsavory example is ye olde Have you stopped beating your spouse and/or kids? My favorite joke from the long dead cartoon show The Critic is a fantastic leading question, along with qualifying for several of the fallacies covered. There is a fire in the skyscraper where Jay Sherman, television critic, shoots his show, and he passes out from the smoke in his dressing room. His chain-smoking coworker finds him, and she carries him down the stairs, drops him on the curb, and lights up another smoke. A TV reporter appears, and says, “Jay Sherman, isn’t this just like the time that the mother lifted the Volkswagen off of her child, except in this case, YOU are the Volkswagen, and the child… is the child in all of us.”

Finally, there is the Fallacy of the Multiple Question, asking a question that suggests things that either haven’t been stated or aren’t true, also known as a leading question. The famous unsavory example is ye olde Have you stopped beating your spouse and/or kids? My favorite joke from the long dead cartoon show The Critic is a fantastic leading question, along with qualifying for several of the fallacies covered. There is a fire in the skyscraper where Jay Sherman, television critic, shoots his show, and he passes out from the smoke in his dressing room. His chain-smoking coworker finds him, and she carries him down the stairs, drops him on the curb, and lights up another smoke. A TV reporter appears, and says, “Jay Sherman, isn’t this just like the time that the mother lifted the Volkswagen off of her child, except in this case, YOU are the Volkswagen, and the child… is the child in all of us.”