For this lecture, please read the introduction and first section of Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.

Kant & Categorical Morality

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804 CE) was born in Konigsberg, capital of Prussia, the largest state of the German empire from 1525 to 1932 that in Kant’s day included much of Northern Germany and Poland. Kant grew up in a devotedly Pietist family, a branch of Lutheranism that placed a great emphasis on individual morality and purity, but Kant found himself drawn to the purity of Rationalism, mathematics and science rather than religious tradition and ceremony. He became a professor at the University of Konigsberg, and never traveled more than fifty kilometers from his hometown in his entire life. He was known for being obsessively punctual, and legend has it that he would take his daily walks after lunch so routinely that housewives would set their clocks by Kant as he passed by their houses. Kant would always walk alone, as he believed it proper and healthy to breathe through one’s nose in the open air and kept his mouth closed outside. He was also deeply disturbed by perspiration. It is said that the only morning Kant broke from his usual strict routine was to purchase a newspaper announcing the outbreak of the French Revolution.

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804 CE) was born in Konigsberg, capital of Prussia, the largest state of the German empire from 1525 to 1932 that in Kant’s day included much of Northern Germany and Poland. Kant grew up in a devotedly Pietist family, a branch of Lutheranism that placed a great emphasis on individual morality and purity, but Kant found himself drawn to the purity of Rationalism, mathematics and science rather than religious tradition and ceremony. He became a professor at the University of Konigsberg, and never traveled more than fifty kilometers from his hometown in his entire life. He was known for being obsessively punctual, and legend has it that he would take his daily walks after lunch so routinely that housewives would set their clocks by Kant as he passed by their houses. Kant would always walk alone, as he believed it proper and healthy to breathe through one’s nose in the open air and kept his mouth closed outside. He was also deeply disturbed by perspiration. It is said that the only morning Kant broke from his usual strict routine was to purchase a newspaper announcing the outbreak of the French Revolution.

Kant was primarily concerned with metaphysics, the laws of being. In ancient Athens, Plato’s idealism and Aristotle’s metaphysics were concerned with the shape and laws of the cosmos, but in early modern Europe, Kant’s idealism and metaphysics are concerned with the shape and laws of the human mind, the ways that understanding and reason work. Kant believed in strict, rule abiding morality, which he considered the true means of Christian salvation, not religious ritual. Using our universal faculty of reason, Kant argued that we can come to understand absolute principles, moral laws which we should always obey no matter the situation or consequences.

Kant was primarily concerned with metaphysics, the laws of being. In ancient Athens, Plato’s idealism and Aristotle’s metaphysics were concerned with the shape and laws of the cosmos, but in early modern Europe, Kant’s idealism and metaphysics are concerned with the shape and laws of the human mind, the ways that understanding and reason work. Kant believed in strict, rule abiding morality, which he considered the true means of Christian salvation, not religious ritual. Using our universal faculty of reason, Kant argued that we can come to understand absolute principles, moral laws which we should always obey no matter the situation or consequences.

In his early work, Kant wrote about philosophy and the natural sciences, reconciling the work of Newton with philosophy and theology. Like Descartes, Kant argued that the regularity of the cosmos shows that it is intelligently designed and operates in a rational manner. Kant says that reason is above and beyond everything human, constraining all rational beings, and that any other rational being, which for Kant would be God and angels but for American philosophy teachers today is often extraterrestrial aliens, would have to admit that universal laws are valid and necessary. This is much like the Mutazilites, rationalists of the earlier Islamic golden age who argued that God was identical with the rationality of the cosmos and was therefore incapable of contradicting himself. Strangely, in his old age Kant hypothesized that the use of domestic electricity caused strange cloud formations and epidemics of disease in cats, a theory which might have survived if Kant had lived in the days of the internet.

In his early work, Kant wrote about philosophy and the natural sciences, reconciling the work of Newton with philosophy and theology. Like Descartes, Kant argued that the regularity of the cosmos shows that it is intelligently designed and operates in a rational manner. Kant says that reason is above and beyond everything human, constraining all rational beings, and that any other rational being, which for Kant would be God and angels but for American philosophy teachers today is often extraterrestrial aliens, would have to admit that universal laws are valid and necessary. This is much like the Mutazilites, rationalists of the earlier Islamic golden age who argued that God was identical with the rationality of the cosmos and was therefore incapable of contradicting himself. Strangely, in his old age Kant hypothesized that the use of domestic electricity caused strange cloud formations and epidemics of disease in cats, a theory which might have survived if Kant had lived in the days of the internet.

As Europe rose to new heights in the 1600s and 1700s, passing the Islamic world in wealth and power, the sciences were discovering many new truths about the world, aided much by mechanical innovations and algebraic math. These new discoveries created an opposition between rationalists, who argued that the world has laws that we can deduce with reason, and empiricists, who argued that we use reason to form assumptions based on experience. One of the most famous empiricists was David Hume, who argued that all human truth is habit, prejudice and assumption, such that we assume one billiard ball causes another to move, a subjective expectation that may not follow. Upon reading the work of Hume, Kant wrote that he had awoken from his “dogmatic slumbers,” now tasked to prove that there is objective truth beyond mere subjective assumptions given that all beliefs are acquired through experience.

As Europe rose to new heights in the 1600s and 1700s, passing the Islamic world in wealth and power, the sciences were discovering many new truths about the world, aided much by mechanical innovations and algebraic math. These new discoveries created an opposition between rationalists, who argued that the world has laws that we can deduce with reason, and empiricists, who argued that we use reason to form assumptions based on experience. One of the most famous empiricists was David Hume, who argued that all human truth is habit, prejudice and assumption, such that we assume one billiard ball causes another to move, a subjective expectation that may not follow. Upon reading the work of Hume, Kant wrote that he had awoken from his “dogmatic slumbers,” now tasked to prove that there is objective truth beyond mere subjective assumptions given that all beliefs are acquired through experience.

Awoken by the skepticism of Hume, Kant spent a ten year “decade of silence”, from 1770 to 1780, working on the first of his three Critiques, the Critique of Pure Reason. Originally, Kant thought the work would take three months. This first Critique focused on what Kant claimed is objective reason exclusively separate from the influence of all experience, something Hume would have flatly denied. Kant’s conception of understanding is often illustrated with the metaphor of eyeglasses. While we may not be able to know what the world looks like without our glasses, we can examine the glasses to see the frame through which we view the world. Kant’s second two critiques, the Critique of Practical Reason and the Critique of Pure Judgement, focused on the use of reason in practical matters, as Practical Reason deals with freedom and morality and Pure Judgement with beauty and art.

Awoken by the skepticism of Hume, Kant spent a ten year “decade of silence”, from 1770 to 1780, working on the first of his three Critiques, the Critique of Pure Reason. Originally, Kant thought the work would take three months. This first Critique focused on what Kant claimed is objective reason exclusively separate from the influence of all experience, something Hume would have flatly denied. Kant’s conception of understanding is often illustrated with the metaphor of eyeglasses. While we may not be able to know what the world looks like without our glasses, we can examine the glasses to see the frame through which we view the world. Kant’s second two critiques, the Critique of Practical Reason and the Critique of Pure Judgement, focused on the use of reason in practical matters, as Practical Reason deals with freedom and morality and Pure Judgement with beauty and art.

As the self experiences the world through its understanding, it finds itself with fundamental categories, which Kant calls foundations, Grundsätze in the German, which also refers to principles. This is why the text we examine today is sometimes translated as the Groundwork of and other times as the Foundations of or Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals. One of these foundations is the category of causation, which Hume considered to be an assumption learned through experience. Kant, targeting Hume, argued that causation is a foundational category that is present in the mind before and apart from all experience, and that we find ourselves categorizing the world in terms of causation in a way that cannot be derived from experience. Another foundational category of Kant’s is substance. For Kant, the mind begins as an empty cabinet rather than a blank slate, with categorical compartments of causation and substance ready to be filled by experiences. Thus, no matter what our individual experiences are, we will all categorize them in terms of causation and substance.

As the self experiences the world through its understanding, it finds itself with fundamental categories, which Kant calls foundations, Grundsätze in the German, which also refers to principles. This is why the text we examine today is sometimes translated as the Groundwork of and other times as the Foundations of or Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals. One of these foundations is the category of causation, which Hume considered to be an assumption learned through experience. Kant, targeting Hume, argued that causation is a foundational category that is present in the mind before and apart from all experience, and that we find ourselves categorizing the world in terms of causation in a way that cannot be derived from experience. Another foundational category of Kant’s is substance. For Kant, the mind begins as an empty cabinet rather than a blank slate, with categorical compartments of causation and substance ready to be filled by experiences. Thus, no matter what our individual experiences are, we will all categorize them in terms of causation and substance.

Kant used the metaphor of an island in a stormy sea to illustrate the rational mind amidst the flux of the sensual world, objective and rational in the sea of the uncertain. Hume famously argued that one cannot derive an ought from an is, that we cannot know what should happen merely based on what is happening. Kant meets Hume halfway. Is and ought are two separate things, the first fashioned by the understanding and the second speculated with reasoning, but for Kant reason can derive what objectively ought to be from what is, insofar as the ideal, universal and absolute shape of our minds is the model we have before our eyes in each and every particular situation. Kant argues that his central example of morality, Never lie, is a necessary conclusion that reason arrives at when it properly surveys itself and understanding. While reason cannot tell us whether we will lie next Tuesday, we can say that it would be objectively wrong to do so given the ideal shape of our minds, much as we cannot say whether we will have four, five or nine muffins next Tuesday, but can say that if we have four, and then get five more, we will certainly and absolutely have nine given the ideal shape our minds give to mathematics.

Nietzsche said Kant was like a fox who admirably broke out of his cage, only to lose his way and wander back into it. Nietzsche disregards all claims to objective truth as mere human interpretations, and so he admires Kant for arguing that reason is free to do as it likes but finds him foolish for arguing that reason must conform to the rational, objective understanding or be wrong. While Kant had hoped to justify and preserve metaphysics, his skepticism towards our knowing the thing-in-itself ultimately lead to the downfall of metaphysics, heralded by Nietzsche.

Nietzsche said Kant was like a fox who admirably broke out of his cage, only to lose his way and wander back into it. Nietzsche disregards all claims to objective truth as mere human interpretations, and so he admires Kant for arguing that reason is free to do as it likes but finds him foolish for arguing that reason must conform to the rational, objective understanding or be wrong. While Kant had hoped to justify and preserve metaphysics, his skepticism towards our knowing the thing-in-itself ultimately lead to the downfall of metaphysics, heralded by Nietzsche.

The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals

In his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), Kant says that ancient Greek philosophers correctly divided philosophy into three sciences, three areas of inquiry where rational reasoning results in coherent understanding: physics, concerned with things and nature, ethics, concerned with people and freedom, and logic, concerned with the form of understanding and reasoning itself. Kant says that just as specialized labor leads to perfection in craft work and being an unspecialized jack-of-all-trades leads to barbarism, we first listen to the philosopher who specializes in the pure forms of understanding and reason before we consider the views of ethicists who specialize in human laws and freedoms.

In his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), Kant says that ancient Greek philosophers correctly divided philosophy into three sciences, three areas of inquiry where rational reasoning results in coherent understanding: physics, concerned with things and nature, ethics, concerned with people and freedom, and logic, concerned with the form of understanding and reasoning itself. Kant says that just as specialized labor leads to perfection in craft work and being an unspecialized jack-of-all-trades leads to barbarism, we first listen to the philosopher who specializes in the pure forms of understanding and reason before we consider the views of ethicists who specialize in human laws and freedoms.

Kant asks if it is possible to empirically construct from our experience a moral science of universal laws that obliges us to follow them with absolute necessity, such as his first and central example, Thou shalt not lie. Here, Kant is stricter than Moses in an absolute and universal way. Just as the fifth of the Ten Commandments says Thou shalt not kill, but technically you can’t murder your fellow people, your neighbors, but can kill enemies in wartime, the eighth commandment says Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor, but technically you can lie to the enemy or your friends about anything other than your neighbors, those of your in-group. Similarly you can’t covet your fellow countryman’s wife. When Kant himself says Thou shalt not lie, he means universally, such that you can’t lie to anyone under any circumstances, no matter who they are or what it costs. I have heard that in one of Kant’s university lectures, he does say that if you are being tortured for information by the enemy, the enemy is not deserving of the truth and you can lie, which if true is quite a contradiction.

Kant asks if it is possible to empirically construct from our experience a moral science of universal laws that obliges us to follow them with absolute necessity, such as his first and central example, Thou shalt not lie. Here, Kant is stricter than Moses in an absolute and universal way. Just as the fifth of the Ten Commandments says Thou shalt not kill, but technically you can’t murder your fellow people, your neighbors, but can kill enemies in wartime, the eighth commandment says Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor, but technically you can lie to the enemy or your friends about anything other than your neighbors, those of your in-group. Similarly you can’t covet your fellow countryman’s wife. When Kant himself says Thou shalt not lie, he means universally, such that you can’t lie to anyone under any circumstances, no matter who they are or what it costs. I have heard that in one of Kant’s university lectures, he does say that if you are being tortured for information by the enemy, the enemy is not deserving of the truth and you can lie, which if true is quite a contradiction.

Kant starts by saying we cannot conceive of anything good without qualification other than goodwill, as even a villain can use reason, logic and mathematics for bad purposes. Unfortunately, if this is the test of what good without qualification is, we can easily think of examples of goodwill used for bad purposes by someone other than the person who has it. Kant further claims that the sight of a being without good will “can never give pleasure to an impartial rational spectator,” and thus a good will is a necessary condition of “being worthy of happiness.” While Kant is a rationalist who thinks thought should be founded on logic rather than tradition, and argues that we can only know the shape our minds give to things rather than the things in themselves, he indisputably believes in a universe that designed human reason and happiness for logical and coherent purposes, unlike Nietzsche.

Kant starts by saying we cannot conceive of anything good without qualification other than goodwill, as even a villain can use reason, logic and mathematics for bad purposes. Unfortunately, if this is the test of what good without qualification is, we can easily think of examples of goodwill used for bad purposes by someone other than the person who has it. Kant further claims that the sight of a being without good will “can never give pleasure to an impartial rational spectator,” and thus a good will is a necessary condition of “being worthy of happiness.” While Kant is a rationalist who thinks thought should be founded on logic rather than tradition, and argues that we can only know the shape our minds give to things rather than the things in themselves, he indisputably believes in a universe that designed human reason and happiness for logical and coherent purposes, unlike Nietzsche.

Kant argues that goodwill is not good because of what it does, because of what good or bad results are obtained intentionally or unintentionally by its actions, but good because it is intrinsically so. It is a jewel that shines by its own light, even if it remains buried and does nothing. Unfortunately, we can thus never prove that goodwill is good using results as evidence of any kind. Kant says that all good reasoning is for the purposes of maintaining good will, which is good in itself, which desires simply further goodwill, without anything beyond this, even happiness. Kant sneaks survival in here however, as goodwill wills itself to continue, which Kant says contradicts and thus invalidates all forms of suicide. Doing what is good simply because it is good and not because it results in anything in particular is doing one’s duty. Kant gives the example of a dealer not overcharging an inexperienced purchaser, charging a child the same as an adult even if they could get away with it.

Kant argues that goodwill is not good because of what it does, because of what good or bad results are obtained intentionally or unintentionally by its actions, but good because it is intrinsically so. It is a jewel that shines by its own light, even if it remains buried and does nothing. Unfortunately, we can thus never prove that goodwill is good using results as evidence of any kind. Kant says that all good reasoning is for the purposes of maintaining good will, which is good in itself, which desires simply further goodwill, without anything beyond this, even happiness. Kant sneaks survival in here however, as goodwill wills itself to continue, which Kant says contradicts and thus invalidates all forms of suicide. Doing what is good simply because it is good and not because it results in anything in particular is doing one’s duty. Kant gives the example of a dealer not overcharging an inexperienced purchaser, charging a child the same as an adult even if they could get away with it.

Furthering goodwill is about securing survival and then happiness, but secondarily and indirectly. Kant argues that the moral worth of an action is not in the expected effect, as good results could be brought about by unconscious robots. Only a free, rational and conscious being could do what is in accord with universal law just because it is good. It is here that Kant makes a gigantic leap for humankind in his reasoning to weld universal reason and pure goodwill together. Kant argues that any goodwilling, rational being should come to the conclusion, the central, guiding moral principle, that they should never act in a way that they do not want everyone else to act always, everywhere, or as Kant writes it, “I am never to act otherwise than so that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law.” Later in the text, he says, “There is therefore but one categorical imperative, namely, this: Act only on that maxim whereby thou canst at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” We use reason to extrapolate our individual action into a universal for all, ask ourselves if we would wish for everyone to do what we want to do to check it against the goodwill we have to see how it feels.

Furthering goodwill is about securing survival and then happiness, but secondarily and indirectly. Kant argues that the moral worth of an action is not in the expected effect, as good results could be brought about by unconscious robots. Only a free, rational and conscious being could do what is in accord with universal law just because it is good. It is here that Kant makes a gigantic leap for humankind in his reasoning to weld universal reason and pure goodwill together. Kant argues that any goodwilling, rational being should come to the conclusion, the central, guiding moral principle, that they should never act in a way that they do not want everyone else to act always, everywhere, or as Kant writes it, “I am never to act otherwise than so that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law.” Later in the text, he says, “There is therefore but one categorical imperative, namely, this: Act only on that maxim whereby thou canst at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” We use reason to extrapolate our individual action into a universal for all, ask ourselves if we would wish for everyone to do what we want to do to check it against the goodwill we have to see how it feels.

Kant says that nothing could be more fatal to morality than that we should wish to derive it from examples. Even Jesus, whom Kant calls, “the Holy One of the Gospels,” can only be recognized as an excellent example by how he is in line with the rational and universal, just as he said that none are good other than God. Kant says we frequently can’t find a single example of a human action that is done purely for duty alone beyond all possible doubt, and that many philosophers have spoken of duty as an instrument for the greatest possible harmony and success of our desires and interests beyond mere duty. This is because we always act in complex circumstances, but we can feel and think with purity, which is the only way we know love and duty to be good.

Kant says that nothing could be more fatal to morality than that we should wish to derive it from examples. Even Jesus, whom Kant calls, “the Holy One of the Gospels,” can only be recognized as an excellent example by how he is in line with the rational and universal, just as he said that none are good other than God. Kant says we frequently can’t find a single example of a human action that is done purely for duty alone beyond all possible doubt, and that many philosophers have spoken of duty as an instrument for the greatest possible harmony and success of our desires and interests beyond mere duty. This is because we always act in complex circumstances, but we can feel and think with purity, which is the only way we know love and duty to be good.

Kant says that many think his position is impossible or impractical, but if we venture beyond the universal, we fall into “self-contradictions, uncertainties, obscurities and instabilities.” If we compromise universal morals, weighing them against our present situation and interests, somewhat moral and somewhat circumstantial depending on circumstances, we are “corrupting them at their very source, destroying their worth.” If it is the duty of a sea-captain to always go down with the ship, it corrupts our adherence to duty itself to allow the feelings that you or your children have about your particular circumstances.

Kant says that many think his position is impossible or impractical, but if we venture beyond the universal, we fall into “self-contradictions, uncertainties, obscurities and instabilities.” If we compromise universal morals, weighing them against our present situation and interests, somewhat moral and somewhat circumstantial depending on circumstances, we are “corrupting them at their very source, destroying their worth.” If it is the duty of a sea-captain to always go down with the ship, it corrupts our adherence to duty itself to allow the feelings that you or your children have about your particular circumstances.

Consider the Guy with the Butcher Knife thought experiment, not an idea of Kant’s but an illustrative example used in ethics classes today. Let us say you are at home, and the doorbell rings. You answer it, and your friend runs in looking afraid and hides in your kitchen. A minute later the doorbell rings again, you answer it, and a scary guy with a butcher knife asks you where your friend is. Kant would not be against shutting the door and saying nothing to the scary guy, but Kant would argue that it is wrong to lie to him and say you don’t know or that your friend took off down the street the other way. Even though we can assume that if you lie it would improve your friend’s chances of living in good health, Kant would argue that this would be wrong, even if your friend ends up killed by the guy you could have lied to. For Kant, it is always wrong to lie, regardless of the consequences.

Consider the Guy with the Butcher Knife thought experiment, not an idea of Kant’s but an illustrative example used in ethics classes today. Let us say you are at home, and the doorbell rings. You answer it, and your friend runs in looking afraid and hides in your kitchen. A minute later the doorbell rings again, you answer it, and a scary guy with a butcher knife asks you where your friend is. Kant would not be against shutting the door and saying nothing to the scary guy, but Kant would argue that it is wrong to lie to him and say you don’t know or that your friend took off down the street the other way. Even though we can assume that if you lie it would improve your friend’s chances of living in good health, Kant would argue that this would be wrong, even if your friend ends up killed by the guy you could have lied to. For Kant, it is always wrong to lie, regardless of the consequences.

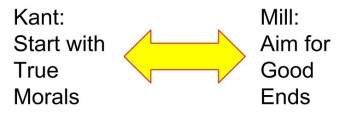

We can contrast this with the position of Mill and Utilitarianism we will study next, which would argue that in some circumstances the lie is the lesser of two evils and one should seek the greater happiness of yourself, your friend and society rather than stick dogmatically to principles and laws. Moralists like Kant believe that we should anchor ethics in good beginnings while empiricists and utilitarians believe we should anchor ethics in good ends. Kant believes that one must start with good intentions and principles no matter the consequences, while Mill believes that one should aim at the best consequences no matter the principles or intentions one has. As usual, both sides agree that one should have good intentions, principles and consequences, but they come down on opposite sides when arguing for what is really the essence or importance of the matter.

While Kant’s position is strong in its universalism, never wavering from principle, it has its drawbacks. Few would argue that it is never acceptable to lie, even if it means saving human lives. Most, when faces with the butcher knife guy thought experiment, find it acceptable to lie if it means improving the chances of living for one’s friend. One recent philosopher, Bernard Williams, who taught at UC Berkeley, even went so far as to accuse Kant and other moralists of moral self-indulgence, valuing the preservation of principle over the preservation of human life. Of course, Kant and other moralists would argue that sticking to principles is the essence of what makes life truly valuable and meaningful, and if we compromise our principles depending on the situation, we put our value of human life in danger itself.

While Kant’s position is strong in its universalism, never wavering from principle, it has its drawbacks. Few would argue that it is never acceptable to lie, even if it means saving human lives. Most, when faces with the butcher knife guy thought experiment, find it acceptable to lie if it means improving the chances of living for one’s friend. One recent philosopher, Bernard Williams, who taught at UC Berkeley, even went so far as to accuse Kant and other moralists of moral self-indulgence, valuing the preservation of principle over the preservation of human life. Of course, Kant and other moralists would argue that sticking to principles is the essence of what makes life truly valuable and meaningful, and if we compromise our principles depending on the situation, we put our value of human life in danger itself.

Kant assumed that human reason, when pure and objective, can determine morals and reasons that were entirely non-contradictory, as he assumed about logic, mathematics and science as well. What happens in situations when our morals contradict themselves? There are two possible cases of contradiction that can arise given a set of morals that are supposed to be followed universally. First, two morals can contradict each other. We can see this in the thought experiment of the guy with the butcher knife. If we have two morals, such as Do Not Lie AND Preserve Human Life, we can find ourselves in situations where if we do not lie we fail to preserve human life. Which moral takes precedence? Which do we follow at the expense of the other? If we are supposed to follow each and every one of our morals universally, regardless of situation, we should not have to choose. Isaac Asimov, the celebrated science fiction author, explored this issue in his novel I, Robot (which was later turned into a movie starring Will Smith that barely resembled the book I loved as a kid). While robots are programmed to preserve the lives of humans, follow human orders, and preserve their own existence, situations arise in which these cannot all be followed that the programmers cannot anticipate. What happens if a robot is ordered to do a task that will destroy itself, but it knows that this will mean it cannot later save human beings or follow further orders?

Second, a single moral can contradict itself. We can see this in the example of the trolley carthought experiment. What if a trolley is going to hit ten people, unless we pull a lever that will make it change course and kill only one instead? Either way, people will die, and the only way to preserve life is to act in a way that will kill someone else. In Asimov’s I, Robot, there are situations where two humans give conflicting orders, and the robot must determine which order to follow and which to ignore.

Second, a single moral can contradict itself. We can see this in the example of the trolley carthought experiment. What if a trolley is going to hit ten people, unless we pull a lever that will make it change course and kill only one instead? Either way, people will die, and the only way to preserve life is to act in a way that will kill someone else. In Asimov’s I, Robot, there are situations where two humans give conflicting orders, and the robot must determine which order to follow and which to ignore.

Humans in ancient times recognized this dilemma. The central and most celebrated part of the Mahabharata, the ancient Indian epic, is the Bhagavadgita, the story of crown prince Arjuna hesitating before fighting a civil war against his family and former friends and teachers. He is counseled by Krishna as an incarnation of Vishnu that as a warrior it is Arjuna’s duty to fight the just fight even if is against everyone else. In the peak moment, Krishna reveals his true self to Arjuna, which is so dazzling, complex and monstrous that Arjuna trembles with fright. Krishna teaches Arjuna that if you do your duty not for yourself but for the cosmos, you are free of doubt and death. In this case, Arjuna is supposed to obey the god and his duty to the cosmos above obeying and preserving the lives of his family and friends.

Humans in ancient times recognized this dilemma. The central and most celebrated part of the Mahabharata, the ancient Indian epic, is the Bhagavadgita, the story of crown prince Arjuna hesitating before fighting a civil war against his family and former friends and teachers. He is counseled by Krishna as an incarnation of Vishnu that as a warrior it is Arjuna’s duty to fight the just fight even if is against everyone else. In the peak moment, Krishna reveals his true self to Arjuna, which is so dazzling, complex and monstrous that Arjuna trembles with fright. Krishna teaches Arjuna that if you do your duty not for yourself but for the cosmos, you are free of doubt and death. In this case, Arjuna is supposed to obey the god and his duty to the cosmos above obeying and preserving the lives of his family and friends.

Aristotle similarly argues, while discussing matters of logic, that it is never right to kill your father, but among the Triballi tribe, the gods sometimes demand it. Since the gods are one’s super-parents and one’s obligations to them supersedes one’s obligations to one’s parents, he says that the Triballi rightly sacrifice their fathers. Once again, obedience to the gods, one’s super-parents, trumps obedience to one’s parents. We find a similar tragic dilemma in the ancient Greek play Antigone by Sophocles. Antigone has two brothers who fight over the title of King of Thebes. After both slay each other, Creon takes the throne and declares that one brother is to be honored as a hero but the other is to be refused burial and left to decay on the battlefield. Antigone, drawn between obeying the dictates of the state and the honor of her family, defies the new king and tries to bury her brother and is condemned to death in court. Antigone is loyal, but she must make a choice: Which is the greater loyalty, family or state? Either way, loyalty to someone is disloyalty to someone else, just as freedom for someone is limitation for someone else.

Also, here is a ridiculous Spanish public service announcement about Kant and riding public transit.

Leave a comment