For this lecture, read Hobbes’ Leviathan, chapters XIII & XIX.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) is often called the second great philosopher (the first being Descartes) in the modern European philosophical tradition. He is known for his 1651 book Leviathan which argues that the people agree to transfer their rights to a sovereign by social contract, and that this agreement justly allows the sovereign to do whatever is necessary to protect the people including use of brute force and deception. Machiavelli, who influenced Hobbes and was the subject of the last lecture, argued that any sovereign must be good at these two evil but necessary aspects of society. Like Machiavelli, Hobbes was a realist and though he supported the traditional monarchy got in trouble even with the loyal Royalists he was trying to support by arguing that the king/sovereign derives authority not from God but from natural law (the basic way humanity and nature work). Like Machiavelli, Hobbes is infamous for supporting the brute power of the king but he is also famous and influential for his discussion of natural rights (self-evident liberties), the equality of humanity, and social contracts (government as an artificial agreement of individuals that concedes power to authority through consent).

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) is often called the second great philosopher (the first being Descartes) in the modern European philosophical tradition. He is known for his 1651 book Leviathan which argues that the people agree to transfer their rights to a sovereign by social contract, and that this agreement justly allows the sovereign to do whatever is necessary to protect the people including use of brute force and deception. Machiavelli, who influenced Hobbes and was the subject of the last lecture, argued that any sovereign must be good at these two evil but necessary aspects of society. Like Machiavelli, Hobbes was a realist and though he supported the traditional monarchy got in trouble even with the loyal Royalists he was trying to support by arguing that the king/sovereign derives authority not from God but from natural law (the basic way humanity and nature work). Like Machiavelli, Hobbes is infamous for supporting the brute power of the king but he is also famous and influential for his discussion of natural rights (self-evident liberties), the equality of humanity, and social contracts (government as an artificial agreement of individuals that concedes power to authority through consent).

Hobbes was working as a tutor and scholar in Florence and Paris, and had been working on a complete physics of natural motions that built up from inanimate objects to the motions of the body to the motions of society. He returned home to England in 1637, finding a country torn by civil wars and complex politics. While things were quite complicated between England, Scotland and Ireland, the two main sides of the English civil war were the Royalists who supported the rule of King Charles the First and the Parliamentarians who supported the rights of nobles in Parliament to check the powers of the king and guarantee liberties for the nobility. Just as in Florence in Machiavelli’s time, there was a brief period (10 years, 1649-1659) of Parliamentary rule after the execution of Charles the First before England returned to monarchy under Charles the Second.

Before the civil war, Parliament was not a permanent body in English government. Parliaments were called at the king’s request to aid the king’s purposes, particularly the collection of taxes and the waging of warfare. Rulers have needed the help of local nobles for these purposes since the earliest city state societies, and so the earliest form of democracy in Sumer was just such a council of nobles as was Athenian democracy (though in Athens there was no ruler for a time above the council). In England before the civil war, Parliament could send bills to be considered as potential laws to the king as well as petition grievances, but the king had the right to call the council as well as dissolve the council, so it was not a permanent body that held the king’s powers in check.

The king needed the nobility, but could also ignore the needs of the nobles for the sake of the crown (according to both Machiavelli and Hobbes, for the greater good of all, embodied in the king). Charles called and dismissed several parliaments that had grievances against him before ruling without a parliament for 11 years. The nobles and later historians called this period the Eleven Years Tyranny, which is ironic if you consider that the nobles held power over the people without any form of representation. Charles was forced to make peace with the kings of France and Spain, to levy great taxes on merchants, and occasionally torture and punish even nobles who rebelled (such as cutting off ears, a punishment common for the commoners but rare for the nobility).

Many in the cities of England and the military favored the parliament, while the rural areas favored the king. Both sides believed that they fought for the traditional English way and wished for Charles to remain on the throne. After several bloody wars and political back-stabbings, the Parliamentarians began to wonder whether Charles should remain king or whether Parliament itself could rule England. Captured by the Parliamentarians, Charles was tried and found guilty of high treason against England, and executed in 1649. English Civil War Societies, much like those in America, reenact the wars every year (but with pikes and shields, not muskets as in America).

At this time, Hobbes was completing his book Leviathan, published the next year in 1650. In Paris he had good contact with Royalists in exile who believed, like Hobbes, that a strong central authority prevented injustice and civil war. The brief period of Parliamentary rule was messy and divided, which the Royalists and Hobbes watched from overseas. In 1660 Charles II returned from exile and re-conquered England and restored the monarchy of his father (a period known as the Restoration). Charles II, who had been tutored by Hobbes as a boy, gave Hobbes protection during times of persecution and a pension.

While the Royalists did in this way win the long fight, only some were delighted by Hobbes’ Leviathan. Many Royalists were outraged by Hobbes’ idea that the king derived authority from the natural rights and protection of the people, not by the divine decree of God. Like Descartes, the first major modern European philosopher, Hobbes got in trouble for saying that we should believe what the authorities say because it makes sense to reason, not simply because the authorities say it. Hobbes does mention God and divine covenants as a basic type of contract, but he argues that one can only enter a contract with God by God’s grace and not by natural right, unlike the mortal human contract that supports a human king. This is why Charles II had to offer him protection during purges of atheism and “profanity” when Hobbes’ book Leviathan was targeted openly. Like Machiavelli, Hobbes was intensely loved and hated and his work spread among those who hated him as much as anyone. While many today loath the idea of a sovereign without checks and balances, Hobbes is important for his ideas about the natural nature of society, liberty, rights, and equality.

In the selections I gave you from Leviathan, some of the most famous, Hobbes argues that in the natural condition, the basic state of humanity in nature, life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short”. Hobbes argues that human beings are more equal than they are different in strength and intelligence. People think that they are above others but this merely confirms their equality (like the DMV reports that 80% of those questioned say they are an above average driver). Everyone wants to obtain their ends and posses what they desire, but because they desire what others want they make enemies easily. Without power over them, there is little happiness and much grief. Each wants safety, even glory, at the expense of the others. The state of nature is therefore a war of all vs. all, a war against every other person.

Hobbes writes that there may never have been such a pure state of nature for all of humanity, but argues that the “savages of America”, the native Americans, live in such a state in his time and thus have no government at all. Rousseau argued the opposite, that the American tribes in the state of nature show us that people were pure and uncorrupted. In the state of nature, when there is no government, nothing is unjust. There is neither justice nor injustice, neither right nor wrong. Force and fraud are cardinal virtues. Consider the similarity with Machiavelli’s Prince here. There is no permanent property that is rightfully one person’s or another’s. The only reason to seek peace is fear of death, which is ironic considering that we call peace a sort of rest when we say “rest in peace”.

For Hobbes, the basic “right of nature” is self-preservation (much like Darwin’s survival of the fittest as a kind of natural law). Hobbes eventually argues that one can pledge one’s life to society, but one still has the right to defend oneself even when society comes to claim this debt. Hobbes draws the useful distinction between a law (a prohibition) and a right (a freedom or liberty). In the state of nature, everyone has the unchecked right to everything, including the lives of others. People should seek peace and form societies for their own sake, but before the social contract there is nothing preventing anyone from doing anything. People should treat others the way they want to be treated, but to do this they have to voluntarily give up liberty. They must give up the liberty of harming others to prevent harm from being done to themselves.

Hobbes makes the further distinction that liberties and rights can be renounced or transferred to another, such as an authority, as people come to understand that they must transfer the liberty of harming others to the sovereign or state in order to ensure mutual peace and prosperity. Once they have entered into such an agreement, a social contract, they have agreed to a standard of justice and this is what creates justice and injustice. Following in accord with the contract is justice, and breaking the contract is injustice. Following the contract creates duty as well as the difference between right and wrong. A declaration of the contract is made by the participants, and now the participants are bound in duty to the contract and the authority in which the contract is embodied.

People naturally want liberty for themselves, but they also wish to dominate others. Unlike other animals, however, people can create voluntary and artificial structures such as social contracts and nation-states. The sovereign is either one person (king, queen, sultan) or a group of people (parliament, congress, pow wow). Hobbes sides with the Royalists against the Parliamentarians in the text and argues that it is best to have a single human sovereign (such as Charles the First or Second), because otherwise there will be civil war and strife like that witnessed in the brief period between Charles the First and Charles the Second. We will soon see that a similar power vacuum following the French Revolution led to terrible fighting and then to Napoleon as emperor.

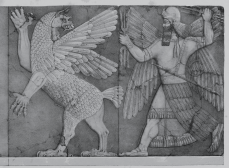

The sovereign, the artificial and mortal God, as Hobbes himself says, is now owed allegiance underneath the authority of the natural and immortal God who only contacts humanity by grace and revelation. When the sovereign acts, it is as if everyone acts. This is famously captured in the image on the front of the publication of Leviathan with a king whose body is made out of the common people, wielding a sword. Because one has pledged one’s strength and life to the sovereign, if you rebel the sovereign actually punishes you with your own hand as well as the hand of everyone else. If the sovereign believes you must be killed for the good of everyone else, it is as if you have condemned yourself to death voluntarily.

Hobbes argues that you still have the right to try to defend yourself, but the social contract makes it right and legal for the king to have the liberty to end your life and the lives of others, foreign and domestic, if it is in the interest of the sovereign who embodies the interests of the whole populace. Also, Hobbes argues that even if the minority does not voluntarily enter the contract, they are bound to it through the interests of the majority and if they do not agree they can be killed without right to safety as this right only exists within the social contract through participation. Consider colonialism, as we will near the end of the class, and how this can be used by foreign powers to set up empires and kill those who disagree in the name of security and liberty.

In the name of the social contract, the sovereign can’t commit injustice. Consider that this was the charge of the Parliamentarians against Charles the First, and the reason Charles was executed while Hobbes is writing the work. The sovereign has the right to censor all works of literature and art, and to decide all matters of property and war. Hobbes quotes the gospels, “A house divided against itself cannot stand”, arguing that there must be an individual who embodies the whole as king or there will be continuous civil war. The king must be “like the sun to the stars”, eclipsing all other authority by right. He writes, “If there had not first been an opinion received of the greatest part of England, that these powers were divided between the King, and the Lords, and the House of Commons, the people had never been divided and fallen into this civil war…and so continue, till their miseries be forgotten”. Consider that Hobbes is arguing against checks and balances to the King’s power, unlike Machiavelli did in his republican works.

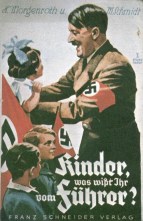

Since we are speaking of unchecked power, it is appropriate to mention fascism as a similarly structured political ideology, one that is surprisingly as Hobbesian and Darwinian on the inside as it is on the outside. Note that the Italian fascist logo here lauds both “Fascism and Liberty“. The word fascist comes from fasces, a tied bundle of rods or sticks. One stick can be easily broken, but many bound together cannot. The ancient Romans used a bunch of rods and an ax tied together as a symbol of Rome under the military commander, the unrivaled emperor, and Roman rulers would often have such a bundle carried in front of them and symbolically present in halls and during speeches. The Italian fascists identified with and glorified Roman power and empire, and they named themselves after the bundle and put it on their flag. These were the first “fascists”, followed soon by German Nazis under Hitler and Spanish fascists under Franco.

Fascism is very much the authoritarianism of Hobbes, and in tune with the Aristotelian notion that civilization is founded on forms of domination and supremacy, but fascism is a modern political movement that bands nationalists together under an authoritarian leader in reaction to modern industrialized times. Fascism is a wide tent that allows for all sorts of followers, but overall it is an authoritarian and nationalist reaction to industrialization and internationalism. Fascists tend towards conservative cultural tastes that reinforce traditional ethnic prejudices and gender norms centered on masculinity, but also embrace modernity with the promises of scientific advancements and a brighter future for (some of) the children of the world.

With the Great Depression of the 1920s, despair was everywhere and left-wing communism offered a way forward for many. In reaction against communism’s anti-religious and anti-nationalist position, others joined the right-wing fascist cause, including many national leaders, upper-class and middle-class people who feared communists would redistribute their property and positions. Mussolini was the first fascist dictator, as the Italians coined the term from the Roman symbol, and he inspired Hitler, who imitated Mussolini and then surpassed him with the resources and technology of Germany, becoming the more famous and infamous fascist.

Here is a picture of Mussolini’s men giving him a “Roman salute”, which is done with the open palm, in the fashion of the Nazi salute, when one doesn’t have an ancient Roman broadsword or a modern Italian military knife. The Pope said that Mussolini was sent by divine providence. Churchill said Mussolini was the Roman genius whose triumphant struggle against communism was a service to the entire world. World leaders praised both Mussolini and Hitler for fighting communists, but when they began expanding their empires, Italy first in Africa and then Germany in Eastern Europe, the British, French and later Americans declared war.