For this lecture, please read chapter 1 &2 of this treatise on Jain beliefs and practices.

Hinduism & Ethics in India

Hindu is the Persian name for India, and English, with the British, took the term from the Persians. Hinduism brought together many traditions from many regions with many gods, just as ancient city states did in Persia and Egypt, but India has a remarkably pluralistic culture in which many conflicting gods and afterlives and practices are all brought together under a single tent and it is all considered to be somehow, mysteriously, the truth beyond what each individual can see. Consider that Hinduism believes both in reincarnation and fixed destinations for afterlives, while the Abrahamic religions ditched reincarnation for the eternal stellar afterlife like the Pharaohs of Egypt. Each branch of Hinduism has its own gods, beliefs and practices, and shares other higher gods, and a highest single father-creator god, and an abstract One and All that transcends anthropomorphic human understandings, the sort of philosophical monism found in Indian, Greek and Chinese philosophy, as well as mysticism the world over. In India, as well as other cultures, philosophers debate what is good and what is true as common people engage in ritual and traditional understandings.

Hindu is the Persian name for India, and English, with the British, took the term from the Persians. Hinduism brought together many traditions from many regions with many gods, just as ancient city states did in Persia and Egypt, but India has a remarkably pluralistic culture in which many conflicting gods and afterlives and practices are all brought together under a single tent and it is all considered to be somehow, mysteriously, the truth beyond what each individual can see. Consider that Hinduism believes both in reincarnation and fixed destinations for afterlives, while the Abrahamic religions ditched reincarnation for the eternal stellar afterlife like the Pharaohs of Egypt. Each branch of Hinduism has its own gods, beliefs and practices, and shares other higher gods, and a highest single father-creator god, and an abstract One and All that transcends anthropomorphic human understandings, the sort of philosophical monism found in Indian, Greek and Chinese philosophy, as well as mysticism the world over. In India, as well as other cultures, philosophers debate what is good and what is true as common people engage in ritual and traditional understandings.

Around 2000 BCE, India was invaded by a fire worshiping people who likely came from what would soon become Persia, today Iran. While scholars previously argued that this was the spark of civilization migrating to India, we know today that the area was already well developed at the time, with great buildings and impressive public baths with plumbing. In the Vedic period, 1500-800 BCE, the four Vedas were composed as oral traditions that eventually were written down in texts. The golden age of Indian thought followed from 800-200 BCE, the time when the Upanishads distilled the Vedic hymns to the gods into philosophical and psychological teachings, as well as the time that many orthodox Hindu and unorthodox non-Hindu schools of Indian philosophy flourished. In this lecture, we will consider some of the basic Ethical teachings of Hinduism and Jainism, the first major unorthodox Indian philosophy. In the next lecture, we will consider teachings of the second and largest unorthodox school of India, a religion larger than Hinduism: Buddhism.

Around 2000 BCE, India was invaded by a fire worshiping people who likely came from what would soon become Persia, today Iran. While scholars previously argued that this was the spark of civilization migrating to India, we know today that the area was already well developed at the time, with great buildings and impressive public baths with plumbing. In the Vedic period, 1500-800 BCE, the four Vedas were composed as oral traditions that eventually were written down in texts. The golden age of Indian thought followed from 800-200 BCE, the time when the Upanishads distilled the Vedic hymns to the gods into philosophical and psychological teachings, as well as the time that many orthodox Hindu and unorthodox non-Hindu schools of Indian philosophy flourished. In this lecture, we will consider some of the basic Ethical teachings of Hinduism and Jainism, the first major unorthodox Indian philosophy. In the next lecture, we will consider teachings of the second and largest unorthodox school of India, a religion larger than Hinduism: Buddhism.

There are three paths of worship in Hinduism. First, there is devotional worship, known as Bhakti yoga (‘yoga’ means ‘discipline’, or practice). In Bhakti devotional worship, the devotee prays, sings hymns, lights incense, and performs rituals to gain favor with the gods and heavens. It is impossible not to notice that most of what we call ‘religion’ the world over is in fact forms of Bhakti practice, devotion to particular gods and ancestral spirits. The two most populous forms of Bhakti Hinduism are Shaivism, the worship of Shiva (the transformer and destroyer) and his incarnations such as Ganesh (the elephant headed god), and Vaishnavism, the worship of Vishnu (the savior or preserver) and his incarnations such as Krishna. Worship is often called darshana, or seeing, both seeing the god and being seen.

There are three paths of worship in Hinduism. First, there is devotional worship, known as Bhakti yoga (‘yoga’ means ‘discipline’, or practice). In Bhakti devotional worship, the devotee prays, sings hymns, lights incense, and performs rituals to gain favor with the gods and heavens. It is impossible not to notice that most of what we call ‘religion’ the world over is in fact forms of Bhakti practice, devotion to particular gods and ancestral spirits. The two most populous forms of Bhakti Hinduism are Shaivism, the worship of Shiva (the transformer and destroyer) and his incarnations such as Ganesh (the elephant headed god), and Vaishnavism, the worship of Vishnu (the savior or preserver) and his incarnations such as Krishna. Worship is often called darshana, or seeing, both seeing the god and being seen.

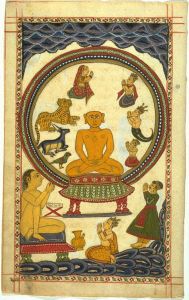

Raja yoga, the second path, is worship by meditation and asceticism (living in isolation, standing in place for days, fasting chanting the names of gods for hours, sitting on spikes, and other means of hard activity) meant to gain a meditative state of insight. Raja means ‘force’ or ‘effort’, and India is famous for its forest sages practicing these techniques. As we will study soon, the Jains and later Buddhists became famous for their practices of discipline, training both the body and the mind. Jains would sometimes stand in the jungle for such long periods of time that vines would grow up their bodies, as depicted in some of their venerated images.

Jnana yoga (“zshna-na”), the third path and my personal favorite, is worship by acquiring knowledge, wisdom and understanding the order of things through study and philosophizing. This class itself could be seen as a form of Jnana yoga, designed to bring you closer to the core by studying the ways of the world. All three paths, or any mixture of the three, are understood to work towards the same goal: liberation from the bonds of attachment and desire, rising into enlightenment and release from the constraints of identity to join together with the whole.

Jnana yoga (“zshna-na”), the third path and my personal favorite, is worship by acquiring knowledge, wisdom and understanding the order of things through study and philosophizing. This class itself could be seen as a form of Jnana yoga, designed to bring you closer to the core by studying the ways of the world. All three paths, or any mixture of the three, are understood to work towards the same goal: liberation from the bonds of attachment and desire, rising into enlightenment and release from the constraints of identity to join together with the whole.

There are two ultimate goals to this process. First, there is hope for a better next life. Many are familiar already with the Hindu idea of reincarnation. This is not a form of afterlife particular to India, but in fact there is evidence that many tribal cultures and early Egypt believed that one’s present life will be reincarnated in another life on earth based on one’s actions and intentions. This interconnection is called karma, which simply means ‘action’ in Sanskrit. Interestingly, physical causation is karma, just as it is also metaphysical causation (next life physics), an understanding of cause and effect applied to a different sphere of existence. If you punch someone in the head, it is karma that makes their head reel backward, and karma that also weighs down your chance for a favorable life after death in the Hindu tradition such that if you punch too many people, you get reborn a cockroach.

There are two ultimate goals to this process. First, there is hope for a better next life. Many are familiar already with the Hindu idea of reincarnation. This is not a form of afterlife particular to India, but in fact there is evidence that many tribal cultures and early Egypt believed that one’s present life will be reincarnated in another life on earth based on one’s actions and intentions. This interconnection is called karma, which simply means ‘action’ in Sanskrit. Interestingly, physical causation is karma, just as it is also metaphysical causation (next life physics), an understanding of cause and effect applied to a different sphere of existence. If you punch someone in the head, it is karma that makes their head reel backward, and karma that also weighs down your chance for a favorable life after death in the Hindu tradition such that if you punch too many people, you get reborn a cockroach.

Second, there is hope for release, for freedom from rounds of rebirth on earth. This can be thought of as dwelling in a heaven with one’s personal or family god, but also as a dwelling with the order of things without residing in any particular place. Bhakti yoga tends to favor the dwelling with a lord, while raja and jnana tends to favor the dwelling with the universe as a whole, however it is important to remember that some Hindus believe that both amount to the same exact thing (while others will insist that their school’s truth is ‘more true’, the same variation one finds in any religion and in our own culture). This release is also called Moksha and Samadhi, but in America we know this first and foremost by the same name as the famous grunge band, Nirvana.

Second, there is hope for release, for freedom from rounds of rebirth on earth. This can be thought of as dwelling in a heaven with one’s personal or family god, but also as a dwelling with the order of things without residing in any particular place. Bhakti yoga tends to favor the dwelling with a lord, while raja and jnana tends to favor the dwelling with the universe as a whole, however it is important to remember that some Hindus believe that both amount to the same exact thing (while others will insist that their school’s truth is ‘more true’, the same variation one finds in any religion and in our own culture). This release is also called Moksha and Samadhi, but in America we know this first and foremost by the same name as the famous grunge band, Nirvana.

While moksha is the ultimate goal, via the more immediate goal of positioning oneself favorably for moksha either in this life (dwelling in the forest or a monastery) or in a next life, there are three other goals that Indian philosophy points to as desirable making four in total. In addition to moksha/nirvana, there is law or morality, dharma (the term Jains and Buddhists use to describe their traditions and rules), pleasure, kama (as from the Kama Sutra), and material well-being or comfort, artha. Clearly, the overall idea is that pleasure and comfort (kama and artha) are not in themselves evil, but one should pursue liberation through discipline (moksha through dharma), first and foremost. Buddhists symbolize dharma with a wheel, one of the earliest images of Buddhism found. Just like early Christians identified with the symbol of the fish before depicting Jesus, Buddhists identified with the wheel before depicting the Buddha.

While moksha is the ultimate goal, via the more immediate goal of positioning oneself favorably for moksha either in this life (dwelling in the forest or a monastery) or in a next life, there are three other goals that Indian philosophy points to as desirable making four in total. In addition to moksha/nirvana, there is law or morality, dharma (the term Jains and Buddhists use to describe their traditions and rules), pleasure, kama (as from the Kama Sutra), and material well-being or comfort, artha. Clearly, the overall idea is that pleasure and comfort (kama and artha) are not in themselves evil, but one should pursue liberation through discipline (moksha through dharma), first and foremost. Buddhists symbolize dharma with a wheel, one of the earliest images of Buddhism found. Just like early Christians identified with the symbol of the fish before depicting Jesus, Buddhists identified with the wheel before depicting the Buddha.

Jainism & The Striver Movement

As the primary Upanishads were being written down and shared between 1000 and 600 BCE, the golden age of ancient Indian thought dawned as many thinkers founded new schools of thought, including the six orthodox schools of Hinduism. There are also many references at the time in texts to “strivers” (shramanas) who were leaving Hinduism and setting off to form new unorthodox (non-Hindu) Indian traditions. Today we call this the Shramana Movement, which gave rise to two of the most famous thinkers in human history: Mahavira (599 – 527 BCE) and the Buddha (563 – 483 BCE). These two distinct but similar seekers were dissatisfied by traditional life and beliefs and went off to seek, learn and practice on their own, often in the jungle beyond civilization. In the Abrahamic tradition of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, similar sorts of strivers traditionally practice in the desert, symbolic of death.

Both Mahavira and Buddha were of the Kshatriya second caste, beneath the Brahmin first and top caste, warrior’s sons who wanted to be priestly philosophers instead. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus, whom some scholars thought wrongly was the Buddha, is also said to be a king who abandoned the throne to become a sage, symbolic of the mind’s superiority to the body, the mental conquering the physical. Both Mahavira and Buddha supposedly left home at age thirty, with Mahavira obtaining enlightenment in twelve years and the Buddha in six. The Buddha and Buddhist tradition follow just after Mahavira and the Jain tradition in years, developing in dialog with each other, so this may possibly be Buddhists claiming the Buddha did what Mahavira did, but in half the time. Jainism, founded by Mahavira, is one of the world’s great religions with five million followers today, most living in India but with communities throughout the world. Buddhism is one of the three largest cultures of human thought in history, along with Christianity and Islam.

One of the stranger parallels in world history is that Jainism was a small, local culture which gave rise to Buddhism, a large, international culture, much as Judaism gave rise to the larger, international cultures of Christianity and Islam. Both Buddha and Jesus taught that diet and ethnicity are not centrally important, creating international traditions out of earlier local teachings. Jains are a minority in India, and have been stereotyped as merchants, traders and bankers who keep wealth amongst their own kind, much as Jews have been similarly stereotyped in Christian and Islamic lands. While both groups have historically suffered charges of usury (profiting from the misfortunes of others), discrimination and exclusion leads to the development of an exclusive, localized community and economy that justifiably looks after communal interests. Because Jains and Jews were excluded from investing in the mainstream community, both invested in cultures of business and trade amongst their own. Both Jains and Jews, small in numbers compared to many cultures, have small communities spread throughout the world that developed over thousands of years along major trade routes. This is in spite of the fact, as we will shortly see, that Jainism is not a philosophy that favors long distance travel.

The Tirthankaras

‘Jain’ means follower of the Jina, the conqueror, the one who conquers themselves. In the Chinese Dao De Jing, an early verse reads, Those who conquer others are powerful, but those who conquer themselves are truly strong. The Jains worship and leave offerings for accomplished human sages who conquer themselves rather than gods, much as Buddhists do, leaving offerings at statues much as Hindus do for gods and sages alike. Just as Buddhists revere the Buddha and other buddhas, the Jains revere the Tirthankaras, the Ford-Makers (tirtha means ford), not originally from Detroit, but there is a sizable Jain community in Toronto nearby, one of the largest outside India. In the American educational video game The Oregon Trail, early (not so PC) versions would ask if the player would like to hire an “Indian” (Native American) guide to help ford a river, crossing where the water is shallow enough for travelers, animals and wagons to walk across. The Tirthankaras are the actually Indian guides who help all sentient beings ford the chaotic river of life to find firmament on the other side, with water symbolic of chaos and death and earth symbolic of permanence and life.

The Jains innovated several ideas which became central to Hinduism as well as Buddhism, including the idea that the cosmos works in cycles. Just as the Sun rises and sets over the course of a day, the Jains claimed that the consciousness of the Cosmos awakens and then falls asleep in each great era (kalpa), destroyed and then reborn, much as ancient Mayan astrologers predicted would happen in 2012. Today, modern physicists debate as to what was before the Big Bang, whether or not there will be a Big Crunch, and whether or not there would be another Big Bang again after such a Big Crunch, with no clear consensus. For the Jains, Buddhists and Hindus, as our own era awakened, humanity began teaching philosophies and religions, and then after the golden age of ancient Indian thought, the apex and high noon of our era, humanity began to “lose religion” and fall into darkness, the time in which we now live.

Jains believe that Mahavira did not create or discover the truth, but rediscovered it, as it is rediscovered at the pinnacle of each era by similar sages of each age. Buddhists refer to Mahavira as “The Boundless One”, without attachments. Jains believe that Mahavira is the 24th and final Tirthankara of our era, the pinnacle of enlightenment, liberation and omniscience that can be achieved in this cycle, just as Buddhists say of the Buddha. Mahavira’s name means Great Hero, and he is revered along with other triumphant heroic Tirthankaras who conquered existence and the mind. Mahavira is said by Jains to have fashioned four fords, the four ordered communities of Jain monks, nuns, laymen and laywomen.

Today, scholars are critical of the existence of Tirthankaras listed before Mahavira in Jain texts just as they are about the existence of Buddhas listed before the Buddha in Buddhist texts. According to the Jains, the first Tirthankara of our era was Rishabha, who discovered agriculture and thus founded civilization. While the ancient Chinese say the same about their ancient sage kings, it is likelier that agriculture and city-states disseminated to both India and China from earlier human cultures, such as the Egyptians and Sumerians. ‘Rishabha’ means bull, and there is evidence of bulls identified with kings in early Indus civilization, much as cows are venerated as sacred by Hindus.

One of the central Jain pilgrimage sites is a towering statue of Rishabha’s second son, Bahubali, the second Tirthankara of our era. According to the story, Rishabha’s first son conquered all of India for himself and forced everyone to submit to his power except his younger brother Bahubali, whose name means Strong Arms. The wise sages of the day declared that the two brothers were virtually invincible, both having obtained unsurpassed spiritual powers, and so the two brothers were asked to settle their dispute with three contests: an eye-fight (also known as a staring contest), a water-fight (splash battle?) and a wrestling match. Bahubali bested his brother in all three, but renounced his claim to the kingdom after he saw the pain and humiliation his brother faced in losing. This parallels second caste Kshatriyas challenging first caste Brahmins, as well as the superiority of the mental sage over the physical warrior. Bahubali stood in the jungle for an entire year without moving, as vines grew up his body, until he became the first in our turn of the great cosmic wheel to obtain complete enlightenment, liberation and omniscience, what Mahavira and Buddha are also said to have obtained through similar sorts of mental and physical disciplinary practices.

Three Viewpoints of Skepticism

The Jains are credited with articulating three doctrines of skepticism and relativity, what are possibly the clearest expressions of philosophical skepticism in all of human history. These are often called ‘principles’, but they are more skeptical perspectives and points of view, tools for understanding truth and meaning, than they are laws or commandments given in words. All three are intended to encourage acceptance and neutrality towards others and their perspectives, particularly when their understandings and interests conflict with our own.

First is anekantavada, the “non-one-sided-view” (vada = view) that things are complexly some and some-not rather than simply all or none. Things that are good are somewhat good in some ways, just as things that are said are somewhat true in some ways. Jains argue against doctrines they consider ekantavada, one-sided and dogmatic. Around 700 CE, fourteen hundred years after Mahavira, the Jain Shvetambara monk Haribhadrasuri wrote an influential work entitled Anekantajayapataka, often translated as The Victory Flag of Relativity.

Second is nayavada, the “perspective-view” that things are known from a particular perspective in a particular situation rather than known universally for all times and places.

Third syadvada, the “maybe-view” that things are known and understood hypothetically, as if our evidence, perspective and reasoning are reliable, rather than known certainly without the possibility of being wrong. The Jains, in dialog with the Nyaya orthodox Hindu school, consider the four sources of evidence (perception, inference, comparison and testimony) to be somewhat reliable but also somewhat unreliable.

The famous parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant is a Jain story which is known throughout the world and used to teach this idea. In the meta-metaphor of many metaphors, several blind men encounter an elephant, and each takes hold of part, encountering reality directly, but then projects that the whole must be like his own part, and gets into an argument with all the others. The one who touches a leg says an elephant is like a pillar, the one with an ear says an elephant is like a sail, the one with the tail says it is like a rope, and the one touching the side says an elephant is like a wall. Each partial perspective is only part of the whole, true in its place but false for those of other positions and parts. The Jains used this idea to argue that there is some truth in every position, but this often blinds us, such that we contradict others from other perspectives, schools and religions, rather than see that there are many paths up the same mountain and many rivers feed into the ocean.

Rumi, the Sufi Muslim poet, retold the story as an elephant in the dark, surrounded by Hindus, showing his awareness of the Indian story’s source. He adds that an elephant’s back is like a throne, and it’s trunk is like a fountain. Like Zhuangzi, the Daoist from China we will study later, Rumi says that we should try to see the ocean, beyond each bubble of foam, and that if each of the Hindus lit a candle, they would all be able to see the elephant as a whole, together.

Another Jain story, found in your reading, is the statue with the gold and silver shield. If a statue facing north has a shield with gold on the front and silver on the back, someone coming into town from the north would see a golden shield while someone coming from the south would see silver, such that the two can get into an argument, each completely convinced by direct evidence of experience that they are correct. We could even imagine the statue has two faces, and each argues that the statue faces them, not their opposite.

Another Jain story, found in your reading, is the statue with the gold and silver shield. If a statue facing north has a shield with gold on the front and silver on the back, someone coming into town from the north would see a golden shield while someone coming from the south would see silver, such that the two can get into an argument, each completely convinced by direct evidence of experience that they are correct. We could even imagine the statue has two faces, and each argues that the statue faces them, not their opposite.

Another Jain parable used to illustrate these principles is The Golden Crown, a simple story about a king with a crown, a prince who desires it and a queen who wants it melted down and made into a necklace. Much as time transforms the old into the new by way of desire, the king agrees with the queen and melts down the crown, making the prince sad. Whether or not the king decides to melt down the necklace and reform the crown, making the queen sad and the prince happy, the king remains happy no matter what happens, as the king cares about the gold, and it remains constant. Whether or not the prince or queen get a reality that coincides with their perspectives and interests, the king retains a perspective that always coincides with his interests, no matter what happens or who wins.

While other schools, including Nyaya logicians, claimed that Jains and Buddhists are at fault for contradicting themselves and seeing contradicting views in things, the Jains and Buddhists argue that we only fall into problematic contradiction if we make one-sided (ekanta) claims about things, ignoring the legitimate contradictory opposite side. Jain texts use the example of hot and cold. If a more absolute-minded logician argues that a thing cannot be both hot and cold at the same time, a relativist would argue that a thing is always somewhat relatively hot and somewhat relatively cold, and to say a thing is simply hot ignores how cold it is, and to say it is simply cold is to ignore how hot it is. We could supply the example of a refrigerator, which cools on the inside by heating up in back and drawing the heat out of the inside. A refrigerator is simultaneously hot and cold, and it could not be cold in one part unless it is hot in another.

Jains also use the example of a pot as both being and non-being, solid and empty, there and not there in a particular arrangement, much as Laozi says in chapter 11 of the Dao De Jing that a wheel or a room is an arrangement of being and nonbeing together. Jains also use the example of a multicolored cloth, which is and is not many colors all over. Notice that each thing one can say about anything is true in some ways, but false in others, a very critical way that things are and are not as they are described yet are never fully describable.

Jains argue that one sees and argues for the side of things that one wants to see, that one wants to be true. Jains argue that because human views and descriptions are always one-sided, it is perfectly alright to understand the whole yet lead people in one direction as opposed to another if one sees what one is doing. It is only a low and ignorant mind that thinks such leading is impossible because it is contradictory. Jains use the image of a tree, with the absolute view as the trunk and the particular view as the branches and twigs. Notice that the trunk is and is not the twigs, just as the absolute and all-encompassing view is each particular view as a sum of them all but is not each particular view in that it is everything opposed to each particular view as well.

Jains argue that one sees and argues for the side of things that one wants to see, that one wants to be true. Jains argue that because human views and descriptions are always one-sided, it is perfectly alright to understand the whole yet lead people in one direction as opposed to another if one sees what one is doing. It is only a low and ignorant mind that thinks such leading is impossible because it is contradictory. Jains use the image of a tree, with the absolute view as the trunk and the particular view as the branches and twigs. Notice that the trunk is and is not the twigs, just as the absolute and all-encompassing view is each particular view as a sum of them all but is not each particular view in that it is everything opposed to each particular view as well.

Similarly, Jains argue that things simultaneously are and are not because they are being birthed/generated, stable/still, and decaying/transforming at the same time at all times that they are. Each of these views are false if they are considered independently true as opposed to their opposite, but in conjunction with their opposites they are the whole truth of each particular thing and of the truth as a whole. The union of stability with transformation as a single whole view is entirely similar to the orthodox Hindu union of Vishnu, the preserver/savior, and Shiva, the destroyer/transformer, in Brahma, the personification of all.

Similarly, Jains argue that things simultaneously are and are not because they are being birthed/generated, stable/still, and decaying/transforming at the same time at all times that they are. Each of these views are false if they are considered independently true as opposed to their opposite, but in conjunction with their opposites they are the whole truth of each particular thing and of the truth as a whole. The union of stability with transformation as a single whole view is entirely similar to the orthodox Hindu union of Vishnu, the preserver/savior, and Shiva, the destroyer/transformer, in Brahma, the personification of all.

Mind Over Matter

Asceticism is severe mental and physical self-discipline, practicing mental meditation and physical exercise while avoiding indulgence and luxury, what is also called raja yoga in the Indian tradition, the second of the three paths of Hinduism. While many of the world’s religions and traditions have ascetic fanatics, such as Christian monks who wear hair-shirts and whip themselves, the Jains are famous for going without food, clothes or any other comforts while meditating and holding yogic postures in the jungle.

Much like Descartes, the first major modern European philosopher who dualistically argued for the separate existence of the mental and the physical, Jains teach that there are two distinct substances that become intermixed in our world, jiva and ajiva, mind and not-mind, spirit and matter, conscious and un/not-conscious. When consciousness is not mixed with and thus obscured by the unconscious, when the mental is not clouded by attachment and involvement with material things, consciousness is naturally perceiving, understanding, powerful and blissful. Jains argue that all of existence shares a single mind which becomes increasingly evident to those who rid themselves of material attachments and involvements. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus, very similar in ways to the Buddha, said that waking we share one world in common, while sleepers each turn into a darkness of their own.

The unconscious (ajiva) does not have any inherent properties of its own, but when it mixes together with consciousness the two combine to create particular types of karma (action), active situations of conscious experience via cause and effect. This is the Jain explanation for the same sort of karma that Hindus, Buddhists and others believe in, governing our present conscious experiences as well as past and future lives. Thus, much as we would say in the frame of modern psychology, our blissful and painful experiences in this life have a cause and effect relationship with our past and future selves and actions. This is how our minds become attached and addicted to particular material things, including the human body, your own as well as the bodies of others. The Jains treat cause and effect between the conscious and unconscious as a material causal process, though like many ancient cultures they incorporate much into the material and natural that we banish to the immaterial and supernatural with modern considerations today.

The Jains and Buddhists use the example of a muddy puddle, which when trampled is opaque but when settled becomes clear. Once the dirt (material) mixes with the water (mental), passions are produced of two different kinds: attraction (positive) and repulsion (negative). Experiences lead to passions, which lead to further experiences. Forms of desire for things and fear of things are the entanglements our minds get into, though we can also perceive and interact with particular things neutrally, without either desire or fear. Through neutrality, we can gain freedom from cycles of cause and effect. The Jains are thus strange determinists who believe we can also earn an increasing freedom of will through neutrality and detachment.

By becoming tranquil, we gain space to shape our relationship with the situations of cause and effect around us, whether or not we strive to become totally detached or remain intermeshed and interactive with them. There is much in both Buddhism as well as Chinese Daoism, incorporated into Buddhism in China, which speaks of this kind of freedom. As we become free through proper practices, abstaining from wrong actions and engaging in good actions, we react less and less to joy and pleasure by becoming attached and less and less to sadness and pain by becoming afraid. For example, when we become more neutral towards possessions, we cease to hoard things we do not need and engage in charity to give others things they need. This in turn makes us unafraid of loss and regarded with appreciation by others.

While the Jains share many of ideas, including several of their own creations, with other Indian traditions, particularly Buddhism, Jains are quite unique in one particular way. While Hindus, Buddhists and many others argue that karma can be either good or bad, Jains argue that involvement with karma, cycles of cause, act and effect, are always bad, always a source of delusion, ignorance and suffering. Jains call karmic particles of matter seeds (bija), which imbed themselves and then sprout in consciousness as experiences, called fruits (phala). Different seeds become fruit at different times and in different ways, consciousness having different experiences arise in different situations. Jains believe we must seek, cook and thus destroy the karmic seeds we have in us in the fires of disciplined, effortful experience, such as the ascetic practice of fasting naked in the jungle for long periods of time.

Those who do the hardest of monastic practices can strengthen themselves against karma in advance, such that future involvements will no longer plant seeds in their minds. Thus, if Jain monks or nuns unfortunately suffer or witness violence, this does not plant seeds of desire for revenge or seeds of fear for death in them. If ethics is the theoretical consideration of why we shouldn’t punch others, Jain monastic practice is the sustained elimination of the desire to punch anyone, regardless of future experience. Buddhists argue against Jains that we should cook the bad behaviorist-seeds out of ourselves, but we can also plant good seeds that result in enlightenment for others and ourselves. For Jains, enlightenment is neutrality and the elimination of involvements, the clarification of what already is.

Jain monastics take five vows to become nuns and monks, vowing to abstain in thought, word and deed (mind, mouth and body) from 1) violence, 2) sex, 3) lies, 4) stealing and 5) possession. These are the most karmic producing activities, the ways that mind becomes most entangled with matter. These vows are considered to be Mahavira’s realization and teaching which created the Jain communities in our era. Jain commoners are not expected to abstain from violence and sex completely, but are educated and encouraged by monks and nuns to avoid doing evil, engage in doing good and attempt to obtain neutrality as much as possible. Monks and nuns are more aware than commoners of the harm we each do to other living things, so commoners are highly encouraged to keep in mind that the harm we do to others is harm we do to ourselves and the good we do for others is the good we do for ourselves.

In the classic Introduction to Ethics dilemma as to whether to lie to Nazis about anyone hiding in the attic, a Jain commoner could lie and sacrifice morality for utility, but nuns and monks are supposed to remain silent rather than lie, even if threatened with death. Similarly, as for the ethical dilemma of Les Miserables, a Jain commoner could steal food when they are starving, but a nun or monk should starve rather than steal. It is for these reasons that Jains, like Buddhists, believe that full practitioners should completely abstain from sex and procreation, as they unfortunately involve us with attachment and fear, as do Nazis and starving.

The Leaky Boat

For Jains, karma is always bondage, always weight that keeps you down, always division or blockage between you and the ALL. Thus, one tries best to avoid accumulating karma and to destroy the karma one has already accumulated. The Jains use another metaphor to teach the dual practice of avoiding karma and shedding karma, what I call the Jain Leaky Boat. Suppose you ride in a boat across water to a distant shore, much as the Tirthankaras forded across before the community could be used as a boat. Water represents chaos and desire, and the land represents firmament and enlightenment. The boat is leaky, with water pouring in, and so you must do two things to get across without sinking.

First, you must plug the leaks so that water stops coming in. For example, Jains take on the discipline (dharma) of a vegetarian diet as a vital part of their ascetic practice, such that they avoid causing harm to animals. When we take steps to reduce stress in our life or better our routine, it is by eliminating negative things.

Second, you must bail out the water that is already in the boat. The Jains call this “shedding” karma, much as we throw off chains or heavy clothes. For example, Jains fast, meditate and stand in yogic postures to cook the seeds of past involvements out of themselves. When we train to strengthen our bodies and minds, it is by engaging in positive things.

Jains believe that it is only by this two-pronged strategy of plugging and bailing, eliminating the negative and engaging in the positive, that the individual can be liberated from desire, suffering and round after round of rebirth into future lives of desire and suffering. From the Tattvartha Adhigama Sutra, a central Jain text, it says:

There is a stoppage of inflow of karmic matter into the soul. It is produced by preservation, carefulness, observances, meditation, conquest of sufferings, and good conduct. By austerities is caused the shedding of karmic matter… Liberation is freedom from all karmic matter, owing to the non-existence of the cause of bondage and to the shedding of the karmas. After the soul is released, there remain perfect right-belief, perfect right-knowledge, perfect perception, and the state of having accomplished all.

Gosala, a sage who was an opponent of Mahavira and Buddha in early texts, taught that we can stop bad karma from coming in but can’t do anything about bad karma already acquired, using a ball of twine to teach that we have to let our past sins unravel on their own accord. Both Mahavira and Buddha taught that rather than simply wait, we can live a disciplined life that not only stops bad attachments and conditioned desires coming in but gets rid of those we have already accumulated. Some today argue that Gosala was somewhat misunderstood by Jains and Buddhists, and that he was not arguing we should do nothing to undo the bad we already have in us but rather that we have no control as to when that bad is resolved, no matter how hard we may want it.

Radical Nonviolence

Much in line with their negative view of all karma, Jain monastics are famous for their radical practices of nonviolence (ahimsa). The average Jain is a commoner, neither a nun nor monk, who does not engage in extremes, but nuns and monks often wear face masks over their mouths outside to prevent insects and microorganisms from flying in and sweep the ground on paths and in areas of ceremony to avoid killing them, as even though the killing would be unintentional, it would still be an accumulation of karmic involvements. While Hindus and many Buddhists are vegetarian, Jains don’t eat root vegetables such as potatoes or carrots as the whole plant must be uprooted and killed. Some only eat what has fallen from plants on its own.

Jains are sponsors of many charities which fight animal cruelty, and Jainism has influenced the world through Gandhi, who was not a Jain but had a Jain teacher Raychandbhai Maheta who taught him about radical nonviolence, and Gandhi had a direct influence on Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, Cesar Chavez, Thich Nhat Hanh, the Dalai Lama and many others.

The Samans and Samanis, are an intermediary group between the ascetics and lay people, men and women who are not full monks and nuns who travel to common people to give the teachings of the purest monks and nuns who choose not to travel and harm the world and organisms in it by doing so. In spite of this, Jains traveled even in ancient times great distances for business and trade. As mentioned, while Jains are sometimes stereotyped as affluent merchants and businessmen in India, Jain monks and nuns own nothing and do not travel.

Leave a comment