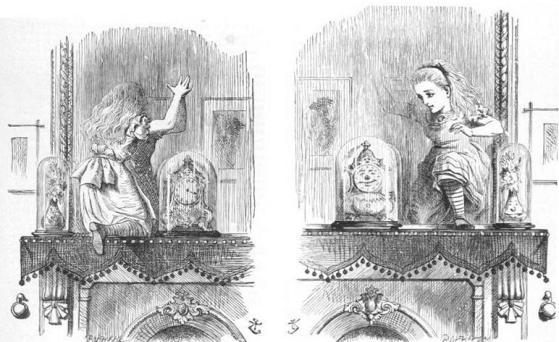

I believe Lewis Carroll used the categories of Aristotle backwards, as if seen in a mirror, to plot out and order the events of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Through The Looking Glass. In Aristotle’s Categories, which Carroll knew well as the first of Aristotle’s works on logic, Aristotle lists the ten types of things we can say about things as substance, quantity, quality, relations, place, time, position, state, action and passion. In Carroll’s mirror-image order, these are passion, action, state, position, time, place, relations, quality, quantity, and substance.

I believe Lewis Carroll used the categories of Aristotle backwards, as if seen in a mirror, to plot out and order the events of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Through The Looking Glass. In Aristotle’s Categories, which Carroll knew well as the first of Aristotle’s works on logic, Aristotle lists the ten types of things we can say about things as substance, quantity, quality, relations, place, time, position, state, action and passion. In Carroll’s mirror-image order, these are passion, action, state, position, time, place, relations, quality, quantity, and substance.

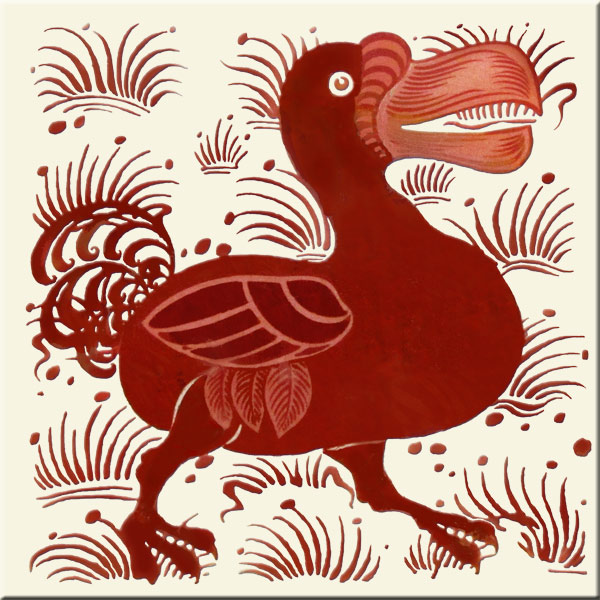

In Wonderland, the White Rabbit is passion, the Mouse is action, the Dodo and his Caucus Race are the state, the White Rabbit’s House is position, the Caterpillar is time, the Cheshire Cat is place, the Duchess is relations, the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party is quality, the Queen of Hearts is quantity, and the King of Hearts is substance. Through the Looking Glass, corresponding exactly chapter by chapter with Wonderland, as if in a mirror, the Black Kitten is passion, the Red Queen is action, the Train is the state, Tweedle Dum and Dee are position, the White Queen is time, the Sheep is place, Humpty Dumpty is relations, the Lion and Unicorn are quality, the White Knight is quantity, and the Queens’ banquet is substance.

In Wonderland, the White Rabbit is passion, the Mouse is action, the Dodo and his Caucus Race are the state, the White Rabbit’s House is position, the Caterpillar is time, the Cheshire Cat is place, the Duchess is relations, the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party is quality, the Queen of Hearts is quantity, and the King of Hearts is substance. Through the Looking Glass, corresponding exactly chapter by chapter with Wonderland, as if in a mirror, the Black Kitten is passion, the Red Queen is action, the Train is the state, Tweedle Dum and Dee are position, the White Queen is time, the Sheep is place, Humpty Dumpty is relations, the Lion and Unicorn are quality, the White Knight is quantity, and the Queens’ banquet is substance.

Some have said Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass are works of nonsense, meant to amuse more than educate. Carroll designed both books to illustrate forms of logic with emotional and unreasonable characters, memorable illustrations and bad examples for Alice to learn and remember well. I have used these to teach students Aristotle and logic, and they work for well. Carroll inverts many things between the two books, but he kept the order of the categories consistent. The lesson of both books is also the overall lesson of Aristotle’s Ethics, balance, avoiding extremes on either side and learning with patience over time and by position between places to make good choices for ourselves and others.

Some have said Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass are works of nonsense, meant to amuse more than educate. Carroll designed both books to illustrate forms of logic with emotional and unreasonable characters, memorable illustrations and bad examples for Alice to learn and remember well. I have used these to teach students Aristotle and logic, and they work for well. Carroll inverts many things between the two books, but he kept the order of the categories consistent. The lesson of both books is also the overall lesson of Aristotle’s Ethics, balance, avoiding extremes on either side and learning with patience over time and by position between places to make good choices for ourselves and others.

There are many more lessons of Aristotle and others hidden in the works, but these are the overall structure and purpose. As Carroll told Alice, we should not go anywhere or do anything without a proper porpoise.

There are many more lessons of Aristotle and others hidden in the works, but these are the overall structure and purpose. As Carroll told Alice, we should not go anywhere or do anything without a proper porpoise.

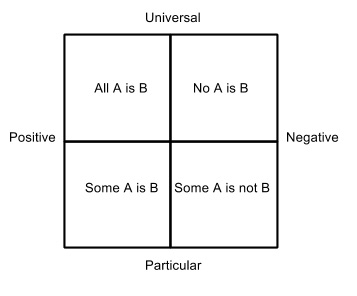

The next logic lesson from Aristotle which can be found that is hidden but central to both of Alice’s adventures is royal characters of the court, the greater pieces of the game and plot, serve as Aristotle’s four types of assertions and corresponding perfect forms of the syllogism, fundamental to Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, well known by Carroll as the second book of Aristotle’s logic, and to many as the four corners of the Square of Opposition.

In Wonderland, the White Rabbit is positive and particular, Some A is B, the Duchess is negative and particular, Some A isn’t B, the Queen of Hearts is negative and universal, No A is B, and the King of Hearts is positive and universal, All A is B. In the Looking Glass, the Red Queen is negative and universal, No A is B, like the Queen of Hearts of Wonderland, the Red King is negative and particular, the White Queen is positive and universal, and the White King is positive and particular, like the White Knight, and like the White Rabbit, in the beginning of Wonderland.

In Wonderland, the White Rabbit is positive and particular, Some A is B, the Duchess is negative and particular, Some A isn’t B, the Queen of Hearts is negative and universal, No A is B, and the King of Hearts is positive and universal, All A is B. In the Looking Glass, the Red Queen is negative and universal, No A is B, like the Queen of Hearts of Wonderland, the Red King is negative and particular, the White Queen is positive and universal, and the White King is positive and particular, like the White Knight, and like the White Rabbit, in the beginning of Wonderland.

The Looking Glass shows what Aristotle calls sub-alternation twice, with each particular king following his universal queen. If we know No A is B, then we also know and later meet Some A isn’t B, the Red Queen leading to the Red King, and if we know All A is B, then we also know and later meet Some A is B, the White Queen leading to the White King, and later White Knight.

The Looking Glass shows what Aristotle calls sub-alternation twice, with each particular king following his universal queen. If we know No A is B, then we also know and later meet Some A isn’t B, the Red Queen leading to the Red King, and if we know All A is B, then we also know and later meet Some A is B, the White Queen leading to the White King, and later White Knight.

Syllogistically, in the Looking Glass, the White Queen, inclusively open like a child, is the universal positive (All, All, All), the Red Queen is the universal negative (All, None, None), the White King is the particular positive (Some, All, Some) and the Red King is the particular negative (Some, None, Some-Not).

Syllogistically, in the Looking Glass, the White Queen, inclusively open like a child, is the universal positive (All, All, All), the Red Queen is the universal negative (All, None, None), the White King is the particular positive (Some, All, Some) and the Red King is the particular negative (Some, None, Some-Not).

In the end, Alice sits as an inclusive-exclusive OR between All and None, as the one who must decide for herself, with her powers of logic and reason, some and some not like an adult between the extremes, as Aristotle advises us in ethics. There are countless examples of syllogistic reasoning in both texts, but here are central examples that show each royal chess piece as an Aristotelian corner. Aristotle starts with the Positive Universal, so Carroll starts with the opposite, not Negative Particular, but Negative Universal, the Red Queen, continuing much as if at the end of Wonderland, with the Queen of Hearts screaming for executions.

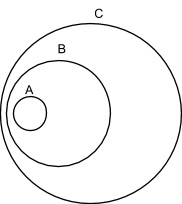

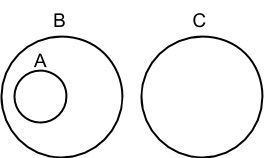

CELARENT, the Negative Universal Syllogism: If All A is B, and No B is C, then No A is C. If All ways are mine, as the Red Queen says, and None of what’s mine is yours, as the Duchess moralizes, then none of these ways are yours, is what the Red Queen means but doesn’t say, which we understand and infer quite syllogistically from what is given in her words. As a Venn diagram, if A is entirely B, and no B is C, then no A can be C.

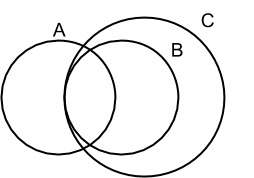

FERIO, the Negative Particular Syllogism: If Some A is B, and No B is C, then Some A is not C. If all things are dreams, as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee tell Alice, and some dreams are untrue or not ours alone, then all things are somewhat untrue, and somewhat aren’t ours alone, which is what Tweedle Dum, Dee and the Red King dreaming silently imply, but don’t say. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and no B is C then some of A is C. As Aristotle says, if we have only some and no all or none, we can’t draw syllogistic judgements completely, leaving us with only a relative, somewhat satisfying conclusion, just as the Red King silently dreams and says nothing to Alice after she happily dances around hand in hand with both twin brothers.

FERIO, the Negative Particular Syllogism: If Some A is B, and No B is C, then Some A is not C. If all things are dreams, as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee tell Alice, and some dreams are untrue or not ours alone, then all things are somewhat untrue, and somewhat aren’t ours alone, which is what Tweedle Dum, Dee and the Red King dreaming silently imply, but don’t say. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and no B is C then some of A is C. As Aristotle says, if we have only some and no all or none, we can’t draw syllogistic judgements completely, leaving us with only a relative, somewhat satisfying conclusion, just as the Red King silently dreams and says nothing to Alice after she happily dances around hand in hand with both twin brothers.

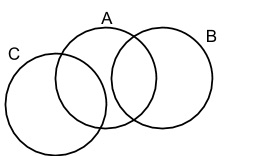

BARBARA, the Positive Universal Syllogism: If All A is B, and All B is C, then All A is C. If all things are possible to think if you Shut your eyes and try very hard, as the White Queen suggests to Alice, and if all impossible things are things indeed, even if they, unicorns and we are all quite mental, then Alice can think six or more impossible things before breakfast if she shuts her eyes, imagines, and tries very hard, as the White Queen implies but doesn’t say directly, meaning what she doesn’t say syllogistically. In Venn diagram form, if A is entirely B, and B is similarly C, then A must also be C.

BARBARA, the Positive Universal Syllogism: If All A is B, and All B is C, then All A is C. If all things are possible to think if you Shut your eyes and try very hard, as the White Queen suggests to Alice, and if all impossible things are things indeed, even if they, unicorns and we are all quite mental, then Alice can think six or more impossible things before breakfast if she shuts her eyes, imagines, and tries very hard, as the White Queen implies but doesn’t say directly, meaning what she doesn’t say syllogistically. In Venn diagram form, if A is entirely B, and B is similarly C, then A must also be C.

DARII, the Positive Particular Syllogism: If Some A is B, and All B is C, then Some A is C. If the White King says he sent almost all his horses along with his men, but not two of them who are needed in the game later, and if Alice has met all the thousands that were sent, 4,207 precisely who pass Alice on her way, then Alice has met some but not all of the horses, namely the Red and White Knights who stand between Alice and the final square where she becomes a queen. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and all B is C then some A must be C.

I have been developing the theory that Lewis Carroll used the logical forms of Aristotle, Boole and De Morgan throughout his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, and both books follow Aristotle’s logical categories in reverse order as the basis for the order of events in the plots of both books, more than any other form I’ve found, and more than any form anyone else seems to have found by far, which means the books are instructional illustrations of forms of logic that are memorable and teachable to both children and adults alike.

I have been developing the theory that Lewis Carroll used the logical forms of Aristotle, Boole and De Morgan throughout his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, and both books follow Aristotle’s logical categories in reverse order as the basis for the order of events in the plots of both books, more than any other form I’ve found, and more than any form anyone else seems to have found by far, which means the books are instructional illustrations of forms of logic that are memorable and teachable to both children and adults alike.

In his Categories, Aristotle starts with what he says is the highest category, substance, and ends with the lowest, passion, but Carroll starts both books with the lowest, passion, and works upwards to substance, opposite the order Aristotle discusses them in his Categories. In Carroll’s mirror-image order, Aristotle’s ten categories are passion, action, state, position, time, place, relatives, quality, quantity, and substance.

In his Categories, Aristotle starts with what he says is the highest category, substance, and ends with the lowest, passion, but Carroll starts both books with the lowest, passion, and works upwards to substance, opposite the order Aristotle discusses them in his Categories. In Carroll’s mirror-image order, Aristotle’s ten categories are passion, action, state, position, time, place, relatives, quality, quantity, and substance.

1) Passion: In Wonderland, Alice follows the White Rabbit out of passion and delight, with no thought as to how she would get out of the rabbit hole. In the Looking Glass, Alice scolds the Black Kitten out of passion and anger, threatening to leave it out in the snow which would surely kill it. Summer outside becomes winter indoors, the White Rabbit becomes a black Kitten, and the passion of delight turns to anger, all mirrored inversions, like the inverted order of Aristotle’s categories in both books.

2) Action: In Wonderland, Alice upsets the Mouse by telling him about her cat, which causes him to act and swim away from her. In the Looking Glass, Alice confuses the Flowers, which cause them to act and mock her, and the Red Queen drags Alice with her instead of fleeing from her like the Mouse, acting on her. The illustration of the Mouse swimming from Alice and the Queen dragging Alice are remarkably similar, and Carroll was exacting about the images, asking for several to be painstakingly redone. Acting away from Alice turns to acting towards Alice, the single Mouse becomes the many Flowers, and Alice forgetting the small size of the Mouse turns to Alice intimidated by the Flowers that tower over her, all inversions.

2) Action: In Wonderland, Alice upsets the Mouse by telling him about her cat, which causes him to act and swim away from her. In the Looking Glass, Alice confuses the Flowers, which cause them to act and mock her, and the Red Queen drags Alice with her instead of fleeing from her like the Mouse, acting on her. The illustration of the Mouse swimming from Alice and the Queen dragging Alice are remarkably similar, and Carroll was exacting about the images, asking for several to be painstakingly redone. Acting away from Alice turns to acting towards Alice, the single Mouse becomes the many Flowers, and Alice forgetting the small size of the Mouse turns to Alice intimidated by the Flowers that tower over her, all inversions.

3) State: In Wonderland, Alice finds herself in a useless caucus race that goes round and round in circles which mocks politics. In the Looking Glass, Alice finds herself on a train with people who read mass printed papers and repeat popular hasty conceptions, mocking the public escalation and industrialization of culture like a train gaining speed on a track, and Alice is told she is going the wrong way by the conductor, not merely her static inverted position, but her state in motion over time. The race round and round going nowhere becomes a train gaining speed down the line of a track, and Alice goes from uselessly going nowhere to wrongly heading down the quickening public track.

3) State: In Wonderland, Alice finds herself in a useless caucus race that goes round and round in circles which mocks politics. In the Looking Glass, Alice finds herself on a train with people who read mass printed papers and repeat popular hasty conceptions, mocking the public escalation and industrialization of culture like a train gaining speed on a track, and Alice is told she is going the wrong way by the conductor, not merely her static inverted position, but her state in motion over time. The race round and round going nowhere becomes a train gaining speed down the line of a track, and Alice goes from uselessly going nowhere to wrongly heading down the quickening public track.

I am posting a longer post today that clarifies both lists.

Some have claimed Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass are both works of nonsense, meant to amuse but not educate, but this is wrong. Carroll designed both books to illustrate forms from the history of logic with memorable, emotional and unreasonable characters. While Carroll mocked the work of Boole, De Morgan and others throughout the two tales, both also primarily serve to illustrate and teach central concepts of Aristotle’s work on Logic, specifically his categories and syllogisms, the forms of Logic that Carroll taught and studied for a living.

Some have claimed Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass are both works of nonsense, meant to amuse but not educate, but this is wrong. Carroll designed both books to illustrate forms from the history of logic with memorable, emotional and unreasonable characters. While Carroll mocked the work of Boole, De Morgan and others throughout the two tales, both also primarily serve to illustrate and teach central concepts of Aristotle’s work on Logic, specifically his categories and syllogisms, the forms of Logic that Carroll taught and studied for a living.

I actually had the chance to use Wonderland this morning to teach Aristotle’s categories to my Greek philosophy students, and one said that it served well to help her visualize and remember each category, as the examples draw on classic memories and are emotively meaningful. This demonstrates the texts are not useless nonsense or mere entertainment, but lesson plans in logic. My theory is that Carroll believed others would find this list of Aristotle’s categories reversed, but when no one noticed he began the sequel Through the Looking Glass with the idea of mirror-images, reversals and putting a text up to the mirror to show that he was inverting Aristotle’s classic text on logic, and going to use inversions and reversals with logic even more in the second story.

I actually had the chance to use Wonderland this morning to teach Aristotle’s categories to my Greek philosophy students, and one said that it served well to help her visualize and remember each category, as the examples draw on classic memories and are emotively meaningful. This demonstrates the texts are not useless nonsense or mere entertainment, but lesson plans in logic. My theory is that Carroll believed others would find this list of Aristotle’s categories reversed, but when no one noticed he began the sequel Through the Looking Glass with the idea of mirror-images, reversals and putting a text up to the mirror to show that he was inverting Aristotle’s classic text on logic, and going to use inversions and reversals with logic even more in the second story.

Alice’s first adventure in Wonderland illustrates Aristotle’s Categories, presenting the ten categories in the order Aristotle discussed them but in reverse: passion, action, state, position, time, place, relatives, quality, quantity, and substance. First, the White Rabbit is passion, who acts on Alice. Second, the mouse is action, acted-upon by Alice. Third, the bird’s caucus race is state. Fourth, Alice takes the position of the White Rabbit’s servant and fills his entire house. Fifth, the Caterpillar is time, who accepts change and uncertainty. Sixth, the Cheshire cat is space, who shows Alice exclusive and opposed positions. Seventh, the Duchess and baby are relatives or relations.

Alice’s first adventure in Wonderland illustrates Aristotle’s Categories, presenting the ten categories in the order Aristotle discussed them but in reverse: passion, action, state, position, time, place, relatives, quality, quantity, and substance. First, the White Rabbit is passion, who acts on Alice. Second, the mouse is action, acted-upon by Alice. Third, the bird’s caucus race is state. Fourth, Alice takes the position of the White Rabbit’s servant and fills his entire house. Fifth, the Caterpillar is time, who accepts change and uncertainty. Sixth, the Cheshire cat is space, who shows Alice exclusive and opposed positions. Seventh, the Duchess and baby are relatives or relations.

Eighth, the Mad Tea Party is quality, with the unsound Hatter and Hare who used the best butter. Ninth, the Queen of Heart’s garden is quantity, with the two, five and seven cards forming an addition problem and the Queen threatening everyone with subtraction. Tenth and finally, the King of Heart’s trial of who stole the tarts is substance, as the tarts are still there substantially but the trial and evidence are insubstantial.

Eighth, the Mad Tea Party is quality, with the unsound Hatter and Hare who used the best butter. Ninth, the Queen of Heart’s garden is quantity, with the two, five and seven cards forming an addition problem and the Queen threatening everyone with subtraction. Tenth and finally, the King of Heart’s trial of who stole the tarts is substance, as the tarts are still there substantially but the trial and evidence are insubstantial.

Alice’s second adventure Through the Looking Glass illustrates the syllogistic forms found in Aristotle’s Prior Analytics in an order that shows subalternation twice. The four royal pieces, the Red Queen, Red King, White Queen and White King, are the four corners of Aristotle’s Square of Opposition, a visual presentation of logic popular in Europe for centuries. The White Queen, inclusively open like a child, is the universal positive (All, All, All), the Red Queen is the universal negative (All, None, None), the White King is the particular positive (Some, All, Some) and the Red King is the particular negative (Some, None, Some-Not). In the end, Alice sits as an inclusive-exclusive OR between All and None, as the one who must decide for herself, with her powers of logic and reason, some and some not like an adult between the extremes, as Aristotle advises us in ethics. There are countless examples of syllogistic reasoning in both texts, but here are central examples that show each royal chess piece as an Aristotelian corner.

Alice’s second adventure Through the Looking Glass illustrates the syllogistic forms found in Aristotle’s Prior Analytics in an order that shows subalternation twice. The four royal pieces, the Red Queen, Red King, White Queen and White King, are the four corners of Aristotle’s Square of Opposition, a visual presentation of logic popular in Europe for centuries. The White Queen, inclusively open like a child, is the universal positive (All, All, All), the Red Queen is the universal negative (All, None, None), the White King is the particular positive (Some, All, Some) and the Red King is the particular negative (Some, None, Some-Not). In the end, Alice sits as an inclusive-exclusive OR between All and None, as the one who must decide for herself, with her powers of logic and reason, some and some not like an adult between the extremes, as Aristotle advises us in ethics. There are countless examples of syllogistic reasoning in both texts, but here are central examples that show each royal chess piece as an Aristotelian corner.

BARBARA, the Positive Universal Syllogism: If All A is B, and All B is C, then All A is C. If all things are possible to think if you Shut your eyes and try very hard, as the White Queen suggests to Alice, and if all impossible things are things indeed, even if they, unicorns and we are all quite mental, then Alice can think six or more impossible things before breakfast if she shuts her eyes, imagines, and tries very hard, as the White Queen implies but doesn’t say directly, meaning what she doesn’t say syllogistically. In Venn diagram form, if A is entirely B, and B is similarly C, then A must also be C.

BARBARA, the Positive Universal Syllogism: If All A is B, and All B is C, then All A is C. If all things are possible to think if you Shut your eyes and try very hard, as the White Queen suggests to Alice, and if all impossible things are things indeed, even if they, unicorns and we are all quite mental, then Alice can think six or more impossible things before breakfast if she shuts her eyes, imagines, and tries very hard, as the White Queen implies but doesn’t say directly, meaning what she doesn’t say syllogistically. In Venn diagram form, if A is entirely B, and B is similarly C, then A must also be C.

CELARENT, the Negative Universal Syllogism: If All A is B, and No B is C, then No A is C. If All ways are mine, as the Red Queen says, and None of what’s mine is yours, as the Duchess moralizes, then none of these ways are yours, is what the Red Queen means but doesn’t say, which we understand and infer quite syllogistically from what is given in her words. As a Venn diagram, if A is entirely B, and no B is C, then no A can be C.

CELARENT, the Negative Universal Syllogism: If All A is B, and No B is C, then No A is C. If All ways are mine, as the Red Queen says, and None of what’s mine is yours, as the Duchess moralizes, then none of these ways are yours, is what the Red Queen means but doesn’t say, which we understand and infer quite syllogistically from what is given in her words. As a Venn diagram, if A is entirely B, and no B is C, then no A can be C.

DARII, the Positive Particular Syllogism: If Some A is B, and All B is C, then Some A is C. If the White King says he sent almost all his horses along with his men, but not two of them who are needed in the game later, and if Alice has met all the thousands that were sent, 4,207 precisely who pass Alice on her way, then Alice has met some but not all of the horses, namely the Red and White Knights who stand between Alice and the final square where she becomes a queen. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and all B is C then some A must be C.

DARII, the Positive Particular Syllogism: If Some A is B, and All B is C, then Some A is C. If the White King says he sent almost all his horses along with his men, but not two of them who are needed in the game later, and if Alice has met all the thousands that were sent, 4,207 precisely who pass Alice on her way, then Alice has met some but not all of the horses, namely the Red and White Knights who stand between Alice and the final square where she becomes a queen. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and all B is C then some A must be C.

FERIO, the Negative Particular Syllogism: If Some A is B, and No B is C, then Some A is not C. If all things are dreams, as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee tell Alice, and some dreams are untrue or not ours alone, then all things are somewhat untrue, and somewhat aren’t ours alone, which is what Tweedle Dum, Dee and the Red King dreaming silently imply, but don’t say. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and no B is C then some of A is C. As Aristotle says, if we have only some and no all or none, we can’t draw syllogistic judgements completely, leaving us with only a relative, somewhat satisfying conclusion, just as the Red King silently dreams and says nothing to Alice after she happily dances around hand in hand with both twin brothers.

FERIO, the Negative Particular Syllogism: If Some A is B, and No B is C, then Some A is not C. If all things are dreams, as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee tell Alice, and some dreams are untrue or not ours alone, then all things are somewhat untrue, and somewhat aren’t ours alone, which is what Tweedle Dum, Dee and the Red King dreaming silently imply, but don’t say. As a Venn diagram, if some A is B and no B is C then some of A is C. As Aristotle says, if we have only some and no all or none, we can’t draw syllogistic judgements completely, leaving us with only a relative, somewhat satisfying conclusion, just as the Red King silently dreams and says nothing to Alice after she happily dances around hand in hand with both twin brothers.