For this lecture, please read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, Introduction.

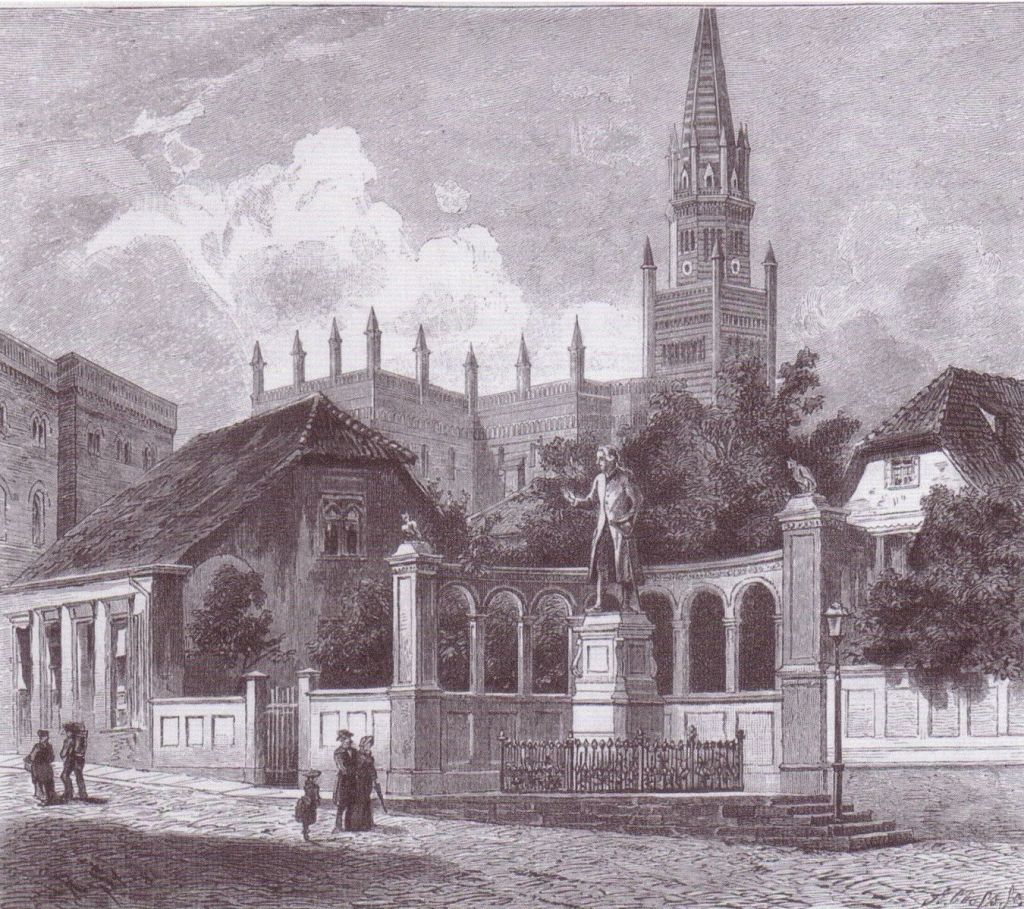

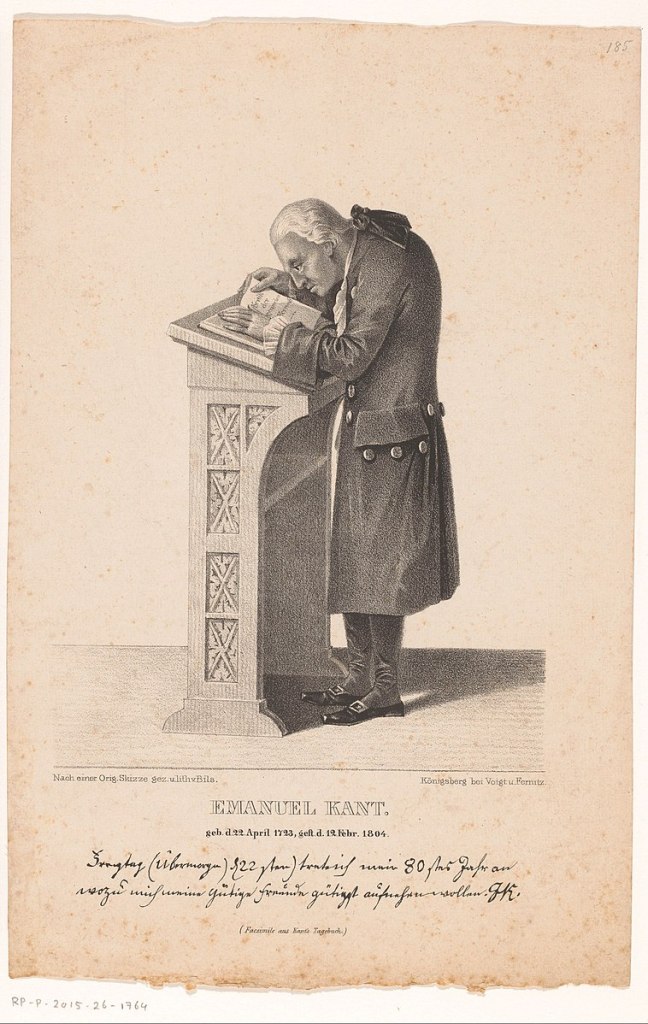

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804 CE) was a German philosopher who was technically born in what was once Königsberg, Prussia, today part of Russia and renamed Kaliningrad. While Kant grew up in a devotedly Pietist family, a branch of Lutheranism that placed a great emphasis on individual morality and purity, he found himself drawn to Rationalism and in opposition to religious ceremony. While a professor at the University of Königsberg, Kant was always “indisposed” whenever it was his turn to participate in church services.

It is said that Kant never traveled more than fifty kilometers from his hometown in his entire life. He was known for being obsessively punctual, and legend has it that he would take his daily walks after lunch so routinely that housewives would set grandfather clocks as Kant passed by their houses. Kant would always walk alone, as he believed it proper and healthy to breathe through one’s nose in the open air and so kept his mouth closed outside. He was also deeply disturbed by perspiration. It is said that the only morning Kant broke from his usual strict routine was to purchase a newspaper announcing the outbreak of the French Revolution, an event that, like the work of Kant, had a great impact on Hegel, the next figure we will study.

It is said that Kant never traveled more than fifty kilometers from his hometown in his entire life. He was known for being obsessively punctual, and legend has it that he would take his daily walks after lunch so routinely that housewives would set grandfather clocks as Kant passed by their houses. Kant would always walk alone, as he believed it proper and healthy to breathe through one’s nose in the open air and so kept his mouth closed outside. He was also deeply disturbed by perspiration. It is said that the only morning Kant broke from his usual strict routine was to purchase a newspaper announcing the outbreak of the French Revolution, an event that, like the work of Kant, had a great impact on Hegel, the next figure we will study.

Just as Locke is famous for his work in both epistemology and political theory, Kant is famous for his work in both epistemology and ethics. While we will focus on Kant’s epistemology for the purposes of this class, just as we focused on Locke’s, we cover Kant’s theory of morality in the Ethics class, which we can briefly cover here just as we briefly covered Locke’s political influence. Kant believed in strict, rule abiding morality, which he considered the true means of Christian salvation, not religious ritual. Using our universal faculty of reason, Kant argued that we can come to understand absolute principles, morals to which we should always adhere no matter the consequences.

Kant argues that if we are rational, we are concerned with absolutes that are universal and ideal. The example Kant gives is, “Do not lie”. If we always lied, society would fall apart, and so we must always tell the truth if we choose to speak rationally. A firm believer in duty, Kant argues that we must be moral no matter the consequences. Even if we know that a lie might have a good chance at saving our own life or the life of another, immorality is never justified. Needless to say, many find this stance a bit to dogmatic to put in practice. John Stuart Mill, who we will study with Utilitarianism, argued for the opposite position, that the ends justify the means, and morality is only for the purpose of achieving happiness.

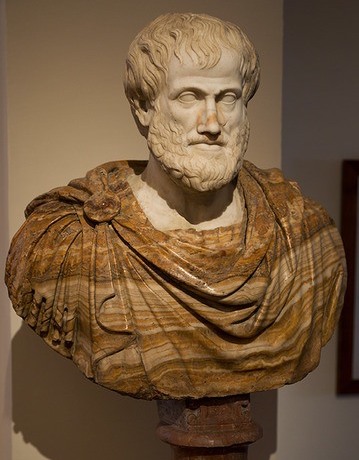

Kant was primarily concerned with metaphysics, the laws of being. Just as Plato’s Idealism was concerned with the heavens while modern Idealism was concerned with the mind, so too Aristotle’s metaphysics was concerned with the workings of the heavenly bodies, while Kant’s metaphysics was concerned with the limitations of the human mind. This is similar to Locke, who was primarily interested in the limits of human knowledge and understanding. Like Leibniz, whom Kant admired and studied, Kant believed in the Principle of Sufficient Reason, the Principle of Non-Contradiction and the rational, universal application of logic, which Kant thought Aristotle had nearly completed. Later, Kant’s work would impact Schopenhauer, whose work would impact Wittgenstein, whose work would completely revolutionize logic, unbeknownst to Kant.

Like Descartes and Hume, Kant was well aware of ancient Greek Pyrrhonism, as well as the challenge that skepticism and the work of Hume posed to metaphysics and Rationalism. Aristotle hated ancient Greek skeptics, arguing that they were “mere destroyers”, and no better than plants when it came to philosophy. Upon reading the work of Hume, Kant famously wrote that he was woken from his “dogmatic slumbers”, now tasked to prove that there is objective truth beyond mere assumptions given that all beliefs are acquired through experience. Kant’s work, like that of Descartes, is concerned with finding what can be defined as certain and objective in the face of doubting everything. Specifically, Kant sought to rescue Leibniz’s Principle of Sufficient Reason and Principle of Non-Contradiction from being considered mere assumptions. He argued that metaphysics could go beyond both dogmatism and skepticism to become ‘critical’, like Descartes questioning all truth to distinguish what is objectively true beyond all appearances.

In his early work, Kant wrote about philosophy and the natural sciences, reconciling the work of Newton with philosophy and theology. Like Descartes, Kant argued that the regularity of the cosmos shows that it is intelligently designed and operates in a rational manner. Strangely, in his old age Kant hypothesized that the use of domestic electricity caused strange cloud formations and epidemics of disease in cats, a theory which might have survived if Kant had lived in the days of the internet.

Awoken by the skepticism of Hume, Kant spent a ten year “decade of silence”, from 1770 to 1780, working on the first of his three Critiques, the Critique of Pure Reason. Originally, Kant thought the work would take three months. This first Critique focused on objective rational inquiry exclusively separate from the influence of experience. Kant’s second two critiques, the Critique of Practical Reason and the Critique of Pure Judgement, focused on the use of reason in practical matters. The Critique of Practical Reason dealt with freedom and morality, and the Critique of Pure Judgement dealt with aesthetics, the study of beauty and art. We focus on the first Critique, as we have been on epistemology. Much as Descartes sought to incorporate while overcoming Pyrrhonian skepticism, Kant sought to incorporate while overcoming Hume’s Empiricism with Rationalism. Kant argued that Hume was right about the world of experience, which can only be known subjectively and imperfectly, but not about the logical operation of reason, which we can know objectively and certainly.

Recall that Locke compared the faculty of understanding to the human eye. Kant’s conception of understanding is often illustrated with the metaphor of eyeglasses. While we may not be able to know what the world looks like without our glasses, we can examine the glasses to see the frame through which we view the world. Likewise, Kant argued that we can critically examine our faculty of understanding with reason to understand how our ideas must take shape, to understand both the basis of understanding and the motions of reason. This would put metaphysics, such as the Principle of Non-Contradiction, “on the secure path of science”. ‘Science’ in German is Wissenschaft, or “knowledge-base”.

Unlike Berkeley, Kant believes that there is a “thing-in-itself” beyond appearances, the Ding an sich in the German, using the Latin term noumena for the things themselves and phenomena for our perceptions of them. Kant argues that we can never know the thing in itself, but we can know the way that we form ideas about appearances. Next week, we will study Phenomenology, the attempt by Hegel, Merleau-Ponty and others to create a “science of appearances”. Kant used another pair of Latin terms to distinguish between rational and empirical truth, to separate the objective from the subjective. That which is known before and apart from all experience Kant labeled a priori, and that which is known after and through experience Kant labeled a posteriori.

Unlike Berkeley, Kant believes that there is a “thing-in-itself” beyond appearances, the Ding an sich in the German, using the Latin term noumena for the things themselves and phenomena for our perceptions of them. Kant argues that we can never know the thing in itself, but we can know the way that we form ideas about appearances. Next week, we will study Phenomenology, the attempt by Hegel, Merleau-Ponty and others to create a “science of appearances”. Kant used another pair of Latin terms to distinguish between rational and empirical truth, to separate the objective from the subjective. That which is known before and apart from all experience Kant labeled a priori, and that which is known after and through experience Kant labeled a posteriori.

The central question of the Critique of Pure Reason is, “How are synthetic a priori judgements possible?”. When we analyze a thing, we break it into its component parts. When we synthesize a thing, we put many parts together to form a greater whole. Kant wants to synthesize, to gather together, what can be known before and apart from experience about the human mind, thus Kant’s concern for the “synthetic a priori”. In a sense, if we sat in a closet and thought, we would be able to form thoughts away from the world, and this would best show us the form our thought takes and thus the form of our world.

If we figure out elementary linear arithmetic in the dark, we may never be able to predict how many coconuts we will gather next Tuesday, but we can be certain that if we gather two coconuts and then three, we will have gathered five coconuts. We can then reason that if we gather six more, we will have eleven, synthesizing additional mathematical truths via reason apart from the experience of gathering any coconuts. Thus, while Hume is right that whatever we think we may gather on a Tuesday is merely an assumption, Kant argues that if we are being objective, we cannot reason two and three together any other way than as the sum of five, giving us a synthesized assumption that is objective and certain, what Descartes sought all along. As mentioned with Descartes, this strangely makes the ideas of logic and mathematics certainties, while the existence of coconuts or Paris, France are merely assumptions.

Essentially, Kant sought to rescue logic, including the Principle-of-Non-Contradiction, from Hume’s charge that all truth is assumption, and he hoped to do this by deducing the principles of logic without relying on assumptions based on experience. This would reveal that logic was truly transcendental, necessary and universal to all experience, the frame through which we must grasp any idea or understanding. While the word transcendent means exclusively removed from and supreme, like a sage who has transcended the world of desires, transcendental means consistently throughout and universal. Wherever one is in the ocean, one would be wet as there is water throughout it.

The American Transcendentalists, such as Emerson and Thoreau, argued that reality is an undivided whole beneath divisions imposed by the mind, a view they found in ancient Indian and Greek thought, and thus the oneness of things is not above and beyond, not transcendent, but within and throughout, transcendental, putting them in the pantheist company of Spinoza. Unlike the Transcendentalists, Kant argued that the objective and subjective should be exclusively divided to prevent misunderstanding and maintain coherence, much as Locke had attempted to divide objective primary qualities from subjective secondary qualities.

Central to this for Kant was the exclusive definition and operation of the faculties of understanding and reason, Verständnis and Vernunft in the German. Hegel took up Kant’s distinction between the faculties of understanding and reason, but influenced by fellow philosopher and friend Schelling, Hegel argued that understanding and reason must be synthesized and united, not exclusively divided. Kant would have considered this the ultimate confusion, arguing in his first Critiquethat the mixing of understanding and reason is a major source of philosophical error as each has properly exclusive jobs to do. For Hegel, Kant’s exclusive division between understanding and reason, as well as the division between the thing-in-itself and our experience of it, were failures of Kant’s inability to synthesize the whole with reason above and beyond the divisions of understanding. While Kant thought that reason should ultimately serve understanding, maintaining exclusive distinctions, Hegel thought that reason should transcend while extending understanding, uniting all in the transcendental One, much like that of the American Transcendentalists.

For Kant, experience requires two separate elements, sensation and understanding. Sensation is the raw content and understanding is the conceptual form that makes sensation coherent. Consider Berkeley’s example of an apple. As we look at an apple, our experience is a union of the undefined sensation and the exclusive categories with which we understand the sensation such as red, solid, apple, and fruit. Without both, there is no coherent experience of the apple.

Kant argues that we can become confused, and believe that the category of ‘apple’ and ‘red’ exist in the world itself, are present in the thing-in-itself, but if we are being rational and exclusive we determine that the categories of understanding are not given in the world but conceptions of the mind, as Hume argued about cause and effect. Thus, the thing-in-itself cannot be known, but the categories of understanding, when exclusive, noncontradictory and coherent, can be known with pure clarity. Unlike Locke’s primary qualities, for Kant the objective is mental, not physical, like the forms of mathematics and logic.

Understanding takes various sensations and synthesizes them into categories, while also exclusively dividing the categories from each other. After we experience several objects, some of which are red, and some of which are apples, we form conceptions of redness and apples. As the self experiences the world through its understanding, it finds itself with pre-existing fundamental categories, which Kant calls foundations (Grundsätzein the German, which also translates as ‘principles’). Hegel was critical of Kant for pulling these categories out of nowhere without describing their development, but Kant believed that the origin of the foundational categories was beyond human comprehension.

Reason serves as a higher level of understanding, just as understanding serves as a higher level of sensation. Just as understanding joins and separates sensations, reason joins and separates understandings. Judgement performs both of these activities, dividing sensations into groups for understanding and dividing understandings into groups for reason. Reason infers similarities and differences of understandings, forming ideas. Ideas, such as freedom and beauty, central examples used by Kant and fleshed out in the second and third Critiques, are not directly experienced in the world but are formed through inferences drawn from the understanding.

Kant’s Königsberg was a traditional stronghold of Aristotelianism. When Aristotle’s work and the work of his ancient Greek commentators was rediscovered in Greek, they made a major resurgence, particularly in Protestant Germany, where Aristotle’s work was disentangled from Catholic and Scholastic issues, leading to a rereading of his work in the original language and apart from its use in Christian theology. Protestant universities founded in the 1500s and 1600s placed Aristotle’s philosophy at the core of their curriculum.

Königsberg University, founded in 1544, established itself as one of the most important Aristotelian universities by the end of the 1600s, publishing many guides and companions to Aristotle’s ideas to explain and establish them as superior, particularly to the thinking of Descartes. Königsberg was also one of the most prominent centers of Locke’s thought in Germany, whose thought, along with Hume’s, was a major British influence on Kant’s own. Kant’s reawakening from his dogmatic slumber, via Hume, is connected with his rediscovery of Aristotle’s categories as a method of overcoming Hume’s skepticism.

Aristotle argued that animals have sensation, and some animals are able to “rest” sensibles in the mind as memory, such that they understand sensibles even when they are not sensing them. For animals that don’t, what is out of sight, or any other sense, is out of mind. Out of these resting, memorable sensibles, concepts form by combining memories of sensibles together. Sensation and memory form conceptions of understanding, which can then be investigated and demonstrated in the world as in line with each thing, constituting true knowledge. This is the position overall argued by ancient Aristotelians, as well as medieval Islamic and Christian philosophers such as Averroes, Aquinas and the scholastics.

In Germany, influenced by several forerunning Aristotelians such as Philipp Melanchthon, Abraham Calov and others, Kant’s thought is similarly based in Aristotelian notions of inductive understanding, judgements that synthesize elements together and analyze elements apart, and the discourse of reason weighing elements and their opposites. Thus we can know, when we confirm our concepts are in line with what we sense, but we can also think, understanding and reasoning beyond what we can know as true, such as when we entertain multiple conflicting, exclusive possibilities which are not yet true and cannot all become true.

For Kant, as for previous German Aristotelians, the proper, fruitful study of philosophy and metaphysics is not focused on particular objects we can know with the senses, but rather on the modes and functions of understanding any object we can sense or reason about. In his lectures, Kant writes that Plato believed in innate ideas in the mind, like Leibniz, but Aristotle did not, like Locke. Thus, Kant argued we can fill the blank slate of the mind with our understanding of our understandings, of the functions of the mind we have even as we start without preformed ideas, and this is the synthetic a priori, what we bring together in concept that starts out as our preset functions of conception.

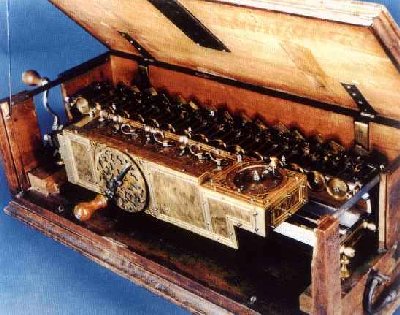

To use a computer metaphor, we may not start out with any software, but if our hardware has several parts that work, we can encode software that traces out the forms of our hardware and how it functions all together as a system. Using the term applied to Aristotle’s works on Logic, Kant writes in the Critique of Pure Reason that, “an organon of pure reason would be a sum total of all those principles in accordance with which all pure a priori cognitions can be acquired and actually brought about… a system of pure reason.” (A 11/B 24-5)

Kant engaged closely with Aristotelian works and logic in the 1770s, as he formulated his ideas and wrote the Critique of Pure Reason, and realized that Aristotle’s doctrine of categories could serve as a better basis for pure laws of understanding and thought than Descartes and Leibniz’s doctrine of innate ideas, in line with Locke’s doctrine of the blank slate of the mind. Kant saw Locke as the new systematizer of Aristotle and investigator of our forms of understanding. However, Aristotle and Locke both hold that all knowledge is empirical and inductive from the world of sensation, much like Hume, Locke’s fellow British empiricist, such that Kant added a further understanding of understandings beyond Aristotle and Locke, the synthetic a priori, which is acquired, but can be purified of sensibles and impressions via critique and pushing reason to its limits, beyond any and all sensible things, arriving at the pure categories.

Kant states in the CPR that Locke went far, but failed because he sought understanding in sensibles (such as square and red) and not in the moves and functions of the understanding itself. (B 127) Locke also, like Ockham and his medieval nominalism, focused on words as symbols we use in ideation, rather than on the non-verbal understanding. This is why Kant is not merely an empiricist, but an idealist, striving for ideas about ideas, even if the extent of his idealism is debated by those who point out Kant does require sensible objects and experience as part of the process of understanding our understandings. In this sense, we acquire true knowledge a posteriori, after experience, of what we have a priori, before experience.

Kant, like Aristotle, argues that the imagination plays a mediary role, extending the particulars we understand through sensation into universals of understanding, which we confirm as knowledge via the process of reason. When we come to Frege and the early work of Wittgenstein, we will see that imagination, visual or otherwise, might not be the mediator that understanding itself is, beneath and beyond imagination. This could depend on terms, if we extend the term imagination to include any understanding of things that could be, in logical relations with other things, whether or not we imagine anything visually or otherwise. If we consider, as Lewis Carroll considers, the middle of next week, is it imagination or understanding that represents something we do not visualize? Either way, for Kant, as for Aristotle, it is the universal form we should seek, not the particular thing we consider, nor what we particularly imagine when we think of it.

Why should we seek the universal forms and categories of the mind, rather than anything particular or sensible? Won’t this lead us away from anything we can determine in particular in the world, and thus anything we can use for any particular purpose? In his earlier work on logic and Leibniz, Kant helpfully illustrates with a fable of the ancient Greek Aesop, about a father who told his lazy sons as he was dying that there was a treasure buried in his field. The sons dug and dug in the field, never finding the treasure, which didn’t exist, but in so doing they tilled the field, yielding fertile crops, and learning the value and results of hard work. Kant thought that by doing logic and completing his Critique, it would clear fertile ground such that understanding and reason could be well applied to anything we undertake. Wittgenstein later stated the same in his introduction to the Philosophical Investigations, as the work is more about clearing out preconceptions than the arrival at a fixed system, yielding the true treasure, a greater ability to think and theorize.

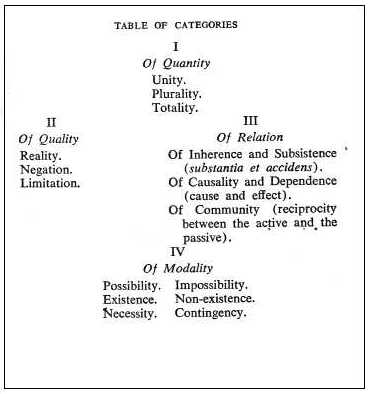

Between 1771 and 1772, about a decade before publishing his first Critique, Kant realized that categories could serve as the answer to his troubles. However, many since Aristotle have found Aristotle’s own list of ten categories to be arbitrary and overlapping, as did Kant, who wrote that Aristotle seems to have stumbled onto his list of ten without following principles to determine them as a system. It is not clear whether or not Aristotle intended his list to be an exhaustive, complete system, or whether they were simply ten topics to talk about. Aristotle’s ten categories, in Aristotle’s own order from his Categories, include: 1) Substance, 2) Quantity, 3) Quality, 4) Relation, 5) Place, 6) Time, 7) Position, 8) State, 9) Action, and 10) Passion. Kant sought a new list, composing a table of four types which each contain three categories:

1) Quantity, which includes: A) Unity (things, objects, this or that), B) Plurality (some, several, of a number) and C) Totality (all, every, each).

2) Quality, which includes: A) Reality (is, yes, true), B) Negation (not, no, false) and C) Limitation (is/not, yes/no, true/false in part, to some extent).

3) Relation, which includes: A) Inherence/Subsistence (substance, property, instances and examples of, in extent), B) Causality/Dependence (if/then, cause/effect, depends/grounds), and C) Community (reciprocity, if/only if, and/or, part/whole).

4) Modality, which includes: A) Possibility/Impossibility (could, may, might), B) Existence/Nonexistence (is/not, will/won’t, does/doesn’t), and C) Necessity/Contingency (must, needs, would).

As Sgarbi argues in his Kant and Aristotle (2016), while Kant’s table is quite different from Aristotle’s list, Kant’s table is quite similar to Aristotle’s eight kinds of judgement in four classes found in his On Interpretation: 1) Affirmation/Negation, 2) Simple/Composite, 3) Particular/Universal, and 4) Possible/Necessary. Kant’s third term for each of the four types is Kant’s own addition, as he states.

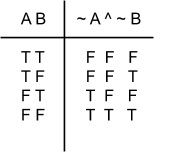

Unfortunately for Kant, many later found Kant’s table of twelve to be much like Aristotle’s list of ten, in that Kant does not show how he systematically derives the twelve, and many of them seem to overlap with each other, such that, like his own criticism of Aristotle’s list, Kant’s table can be further analyzed and systematized. Later, Wittgenstein offered his truth tables to further the work of Frege, which served a very similar role, reducing the modes of thought to operations such as AND, OR, and IF/THEN. As a result, just as Aristotle’s ten categories was largely ignored after the scholastics, Kant’s table of categories was largely ignored by Neo-Kantians such as Frege as they continued to refine formal logic.

To further complicate, or perhaps simplify things, according to Kant scholar Paul Guyer, Kant sometimes suggests that there are really five categories, sometimes four, and sometimes three, and Kant seems to give no explanation as to why or how he reduces his table. The simplest, most refined three include 1) Substance, 2) Causation, and 3) Composition, which Kant claims allows us to employ categorical, hypothetical, and disjunctive forms. This resembles the AND, IF/THEN and OR of Wittgenstein’s basic truth table operations. Perhaps this is what Frege was thinking when he overlooked Kant’s table of twelve and centered his own work on logical combinatory operations.

For Kant, it is crucial to keep reason separate from understanding. Reason is transcendent, beyond sensations and understandings, whereas understanding is transcendental, throughout sensations and reasonings. Reason is separate from the sensible world, and thus free to form ideas. This corresponds to Descartes’ dualism, dividing the determined body from the free mind, except for Kant both understanding and reason are mental. While the understanding is passive, categorizing sensation as it happens, reason is active, producing ideas as it sees fit. Experience is determined by the understanding, but ideas are formed from the free use of reason within the imagination, separate from, though derived from, experience and understanding.

For Kant, reason is free to wander, taking a wider view, forming abstract ideas and speculating about what might be, however it may not contradict the understanding. For Hegel, reason’s job is to extend but also contradict understanding, to contradict accepted dogmas with opposite points of view and force progressively greater synthesis beyond exclusive boundaries. For Kant, contradiction with the understanding results in incoherence, an improper mixing of understanding and reason, not a greater synthesis of knowledge. For Hegel, understanding is extended by contradiction, transforming the incoherent into the coherent. Both believe that reason works through dialectic, by weighing both sides of a potential judgement and then extending the understanding, arriving at a greater understanding than before. Should reason never result in contradiction, or should it contradict itself and then overcome the contradiction? It depends on whether one accepts or opposes the Principle of Non-Contradiction.

For Kant, understanding has jurisdiction over things, whereas reason has jurisdiction over ideas. In this sense, while the understanding categorizes things, such that we experience things as substances that cause and are affected, our ideas of substance and causation are part of our free, abstract reasoning, which judges the categories of the understanding to produce abstract ideas. This would mean that ‘substance’, ‘nature’ and ‘beauty’ are ideas, not things, produced by reason, not experienced in the world.

In both epistemology and ethics, Kant argues that we are free, but we are merely free to find the singular, necessary and objective truth or to be mistaken and confused depending on whether we are being objective and rational. Bill Hicks, the comedian quoted earlier, had a bit mocking American television, shouting, “You are free to do as we tell you!” This is disturbingly similar to the Nazis posting, “Work is Freedom” above the entrances to the concentration camp at Auschwitz, an inspiration to George Orwell as he wrote doublespeak slogans for the tyrannical Big Brother government of his novel 1984, such as “War is Peace”.

Kant used the metaphor of an island in a stormy sea to illustrate the rational mind amidst the flux of the sensual world, objective and rational in the sea of the uncertain. Schopenhauer, a Kantian, used a similar metaphor of a ship on a stormy sea, more skeptical than Kant as a boat is not fastened down but drifts with the current of the passions. While the understanding is passive, and can only judge sensations as they happen, reason is free to speculate as to what could, or should happen. Hume famously argued that one cannot derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’, that we cannot know what should happen merely based on what is happening. Kant meets Hume halfway. ‘Ought’ and ‘is’ are two separate things, as Hume argued, but for Kant reason can derive what objectively ought to be. Kant’s central example of morality, “Do not lie”, is a necessary conclusion that reason arrives at when it properly surveys the understanding and speculates with ideas. The conclusion is seen by reason to be universal, necessary, and objective. Thus, while reason cannot tell us whether we will lie next Tuesday, we can say that it would be objectively wrong to do so.

Nietzsche said Kant was like a fox who admirably broke out of his cage, only to lose his way and wander back into it. Nietzsche disregards all claims to objective truth as mere human interpretations, and so he admires Kant for arguing that reason is free to do as it likes but finds him foolish for arguing that reason must conform to the rational, objective understanding or be wrong. While Kant had hoped to justify and preserve metaphysics, his skepticism towards our knowing the thing-in-itself ultimately lead to the downfall of metaphysics, heralded by Nietzsche.

Realists, like the Scottish Realists who had an impact on Analytic philosophy, thought that Kant had gone too far in agreeing with the skepticism of Hume. Similar to Johnson kicking the rock, Realists argue that it is ridiculous to speak of causation and substance as assumptions or categories of the mind, as they are clear and objectively present in the world. The question is, when is it worthwhile to question our conceptions of causes and substances?

Questions for discussion:

1) Kant hoped to overcome Hume’s skepticism with Aristotelian categories of pure understanding and reason. Does his project succeed? What are the strengths and faults of Kant’s position, contra Hume?

2) Kant extended the work of Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley and Hume, particularly about skepticism and our ability to attain universal knowledge. Does Kant’s position improve or impoverish empiricism?

Sources & Further Reading:

The Cambridge Companion to Kant, ed. by Paul Guyer, Cambridge, 1992

Kant & Aristotle: Epistemology, Logic, & Method, by Marco Sgarbi, SUNY, 2016

Kant & the Transcendental Object: A Hermeneutic Study, Clarendon Press – Oxford, 1981