For this lecture, read parts 1 – 3 of Descartes’ Discourse on Method.

RENE DESCARTES (1596-1650), known as the first great modern European philosopher, wrote the first canonical modern European philosophy texts, his Discourse on Method and his Meditations. He is also known in mathematics for the Cartesian coordinate system (X and Y as two dimensions), a device useful for visually displaying algebraic equations and critical for the later European development of calculus by Newton and Leibniz. The word Cartesian is used, rather than Decartesian, to refer to things that are of or like Descartes, such as his followers, the Cartesians, his coordinate system and his dualism between body and mind.

Descartes was born in Touraine, France, a town which has since been renamed Descartes after its most famous citizen. Descartes’ father was a member of parliament, though his mother died when he was very young. He went to law school to follow his father and become a merchant, but decided to become a mercenary instead and fight in the 30 Years War “to seek truth“, in his words. It seems that he did not find truth in law school. As a soldier, he had much time waiting for battle, and studied mathematics and science in his spare time. On the night of November 10th, 1619, Descartes had a series of visions that convinced him that the world is a rational and mechanical system profoundly in tune with the rationality of the human mind. Note that, before Europe received much of basic mechanics from China and algebra from Muslims, Descartes would have little reason to view nature as a mathematical machine.

Descartes was born in Touraine, France, a town which has since been renamed Descartes after its most famous citizen. Descartes’ father was a member of parliament, though his mother died when he was very young. He went to law school to follow his father and become a merchant, but decided to become a mercenary instead and fight in the 30 Years War “to seek truth“, in his words. It seems that he did not find truth in law school. As a soldier, he had much time waiting for battle, and studied mathematics and science in his spare time. On the night of November 10th, 1619, Descartes had a series of visions that convinced him that the world is a rational and mechanical system profoundly in tune with the rationality of the human mind. Note that, before Europe received much of basic mechanics from China and algebra from Muslims, Descartes would have little reason to view nature as a mathematical machine.

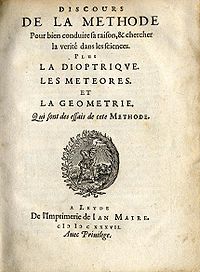

At first, Descartes intended on writing a book on physics, his Treatise on the World, but in 1633 Galileo was condemned by the Catholic Church for his theory that the earth moves around the sun, a theory that posits the sun at the center of the solar system and universe instead of the earth. Because of Galileo’s troubles, Descartes decided to publish his Discourse on Method instead, and it is today considered the first major work of modern European philosophy.

At first, Descartes intended on writing a book on physics, his Treatise on the World, but in 1633 Galileo was condemned by the Catholic Church for his theory that the earth moves around the sun, a theory that posits the sun at the center of the solar system and universe instead of the earth. Because of Galileo’s troubles, Descartes decided to publish his Discourse on Method instead, and it is today considered the first major work of modern European philosophy.

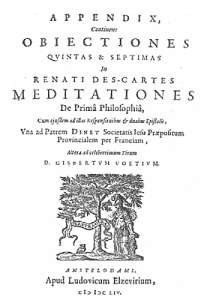

This caution did not spare Descartes however, as the work was condemned by the Pope in 1663, thirty years after Galileo’s work was condemned and after Descartes’ death, and it was put on the prohibited index of books alongside many others that are foundational for the European Enlightenment. Even though Descartes, like Aquinas, argued that reason teaches us that the Catholic Church is the one true religion, his heresy was teaching that it is reason that shows us this, not the authority of the Church or objectivity itself. Descartes remained a practicing Catholic until his death.

This caution did not spare Descartes however, as the work was condemned by the Pope in 1663, thirty years after Galileo’s work was condemned and after Descartes’ death, and it was put on the prohibited index of books alongside many others that are foundational for the European Enlightenment. Even though Descartes, like Aquinas, argued that reason teaches us that the Catholic Church is the one true religion, his heresy was teaching that it is reason that shows us this, not the authority of the Church or objectivity itself. Descartes remained a practicing Catholic until his death.

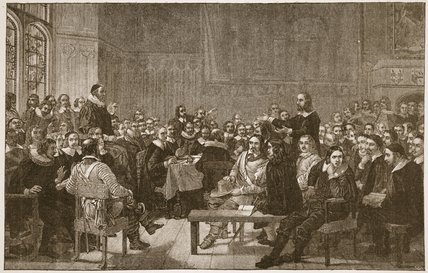

As the skeptical philosopher of science Feyerabend notes, the Church did not merely stand for ignorance, but supported the philosophers and scientists whose work did not conflict with its dogmas, as do institutions in general. As far as the Church was concerned, it was the work of Descartes and Galileo that was in conflict with reason and experience already acquired, matters of debate for centuries between philosophers and theologians within the institution. If one assumes that the Bible is an authentic record of human experience, and if it appeals to human reason in telling everyone to seek the light and be critical of humanity, it is not difficult to assume that Descartes and Galileo are in contradiction with the science of their day, supported by the institution of the Church, the highest science of the time being theology. According to Feyerabend, Galileo looked through a telescope and saw some things that contradicted Church dogma, but missed other things he could have seen that later scientists would explore.

As the skeptical philosopher of science Feyerabend notes, the Church did not merely stand for ignorance, but supported the philosophers and scientists whose work did not conflict with its dogmas, as do institutions in general. As far as the Church was concerned, it was the work of Descartes and Galileo that was in conflict with reason and experience already acquired, matters of debate for centuries between philosophers and theologians within the institution. If one assumes that the Bible is an authentic record of human experience, and if it appeals to human reason in telling everyone to seek the light and be critical of humanity, it is not difficult to assume that Descartes and Galileo are in contradiction with the science of their day, supported by the institution of the Church, the highest science of the time being theology. According to Feyerabend, Galileo looked through a telescope and saw some things that contradicted Church dogma, but missed other things he could have seen that later scientists would explore.

Descartes’ death is famous and unfortunately funny. For the majority of his life, he worked in bed until noon each day, an aristocrat who had the time and leisure to do this. After he became famous and his works were prohibited by the Catholic Church, the Protestant Queen Christina of Sweden invited him to Stockholm to be her private tutor. Unfortunately for Descartes, she wanted lessons each and every morning at five o’clock. Between the snow and the early mornings, Descartes was soon sick with pneumonia, and died. Maybe we should all work on our problems every day until noon, safe in bed. This is similar to Sir Francis Bacon’s famous death, catching pneumonia after repeatedly stuffing snow into chickens to try to preserve the meat and keep it from rotting. Some Swedes reported that Descartes was killed with a poisoned communion wafer given to him by a priest but the sources on this are questionable and it is likely this story was invented by Swedish protestants.

Descartes’ death is famous and unfortunately funny. For the majority of his life, he worked in bed until noon each day, an aristocrat who had the time and leisure to do this. After he became famous and his works were prohibited by the Catholic Church, the Protestant Queen Christina of Sweden invited him to Stockholm to be her private tutor. Unfortunately for Descartes, she wanted lessons each and every morning at five o’clock. Between the snow and the early mornings, Descartes was soon sick with pneumonia, and died. Maybe we should all work on our problems every day until noon, safe in bed. This is similar to Sir Francis Bacon’s famous death, catching pneumonia after repeatedly stuffing snow into chickens to try to preserve the meat and keep it from rotting. Some Swedes reported that Descartes was killed with a poisoned communion wafer given to him by a priest but the sources on this are questionable and it is likely this story was invented by Swedish protestants.

Descartes’ philosophical writings, particularly the Meditations, drew the reactions of several philosophers who themselves went on to become famous, particularly Spinoza, Hobbes, Hume, Leibniz, and Locke. In the Meditations, Descartes asks: What we can know for certain if it is possible that everything is an illusion of the mind? Like Avicenna, Descartes concludes that we can be certain that we are aware and conscious. From this, he proceeds to conclude that we can be certain that our thoughts are our own, that there is a good and loving monotheistic god who would not deceive us about these things, and thus that the world is real, that there are things in the world that we can know for certain. Some philosophers agreed with this very much, but did not find Descartes’ argument convincing and tried to come up with more satisfying proofs. Other philosophers who were more skeptical did not buy it and argued that human certainty is gathered through experience, not simply known mathematically via pure reason. These two sides of the debate became known as Rationalism and Empiricism.

Descartes’ philosophical writings, particularly the Meditations, drew the reactions of several philosophers who themselves went on to become famous, particularly Spinoza, Hobbes, Hume, Leibniz, and Locke. In the Meditations, Descartes asks: What we can know for certain if it is possible that everything is an illusion of the mind? Like Avicenna, Descartes concludes that we can be certain that we are aware and conscious. From this, he proceeds to conclude that we can be certain that our thoughts are our own, that there is a good and loving monotheistic god who would not deceive us about these things, and thus that the world is real, that there are things in the world that we can know for certain. Some philosophers agreed with this very much, but did not find Descartes’ argument convincing and tried to come up with more satisfying proofs. Other philosophers who were more skeptical did not buy it and argued that human certainty is gathered through experience, not simply known mathematically via pure reason. These two sides of the debate became known as Rationalism and Empiricism.

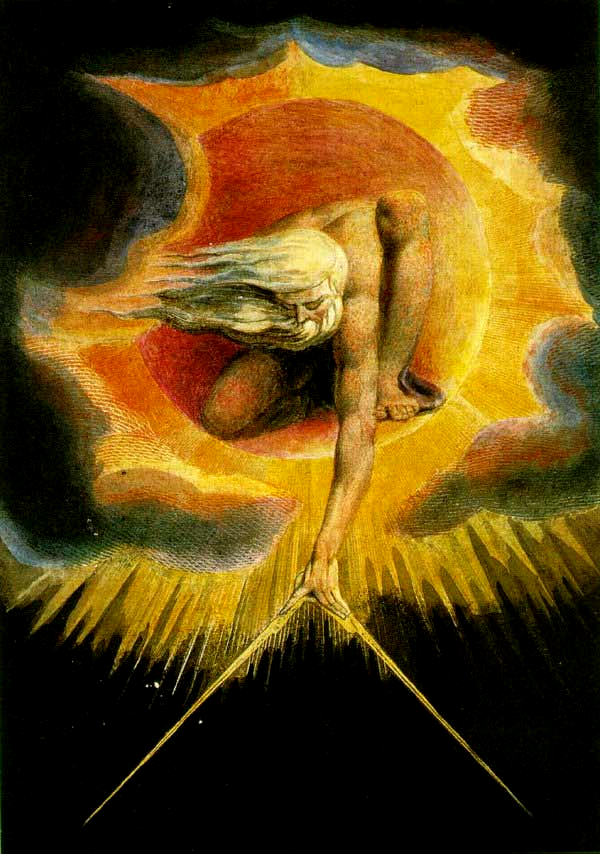

In a world of increasing algebra and mechanics, Descartes turns from an ancient understanding of causes up in the heavens above, acquired through centuries of charting the stars and the seasons, to an understanding of causes in the mechanics of this world below. While Descartes argued that a monotheistic god clearly created the world, as reason tells us all things have causes, he was condemned like Hobbes, Newton and others for arguing that nature works like a machine, and once caused proceeds largely on its own. Descartes argued that the natural world, including animals and human bodies, are mechanical and unconscious, like a mechanical clock and unlike a human mind, and that the human mind and body are exclusively separate, a position known as Cartesian dualism. The worst consequence of this was that Descartes practiced vivisection, cutting animals apart while still alive to learn about anatomy, and argued that animals do not have minds, feel nothing, and merely appear to behave as if in pain. In one place, he even argued that the mistaken belief that animals can have conscious sensations is one of the worst obstacles to the progress of science and rationality.

In a world of increasing algebra and mechanics, Descartes turns from an ancient understanding of causes up in the heavens above, acquired through centuries of charting the stars and the seasons, to an understanding of causes in the mechanics of this world below. While Descartes argued that a monotheistic god clearly created the world, as reason tells us all things have causes, he was condemned like Hobbes, Newton and others for arguing that nature works like a machine, and once caused proceeds largely on its own. Descartes argued that the natural world, including animals and human bodies, are mechanical and unconscious, like a mechanical clock and unlike a human mind, and that the human mind and body are exclusively separate, a position known as Cartesian dualism. The worst consequence of this was that Descartes practiced vivisection, cutting animals apart while still alive to learn about anatomy, and argued that animals do not have minds, feel nothing, and merely appear to behave as if in pain. In one place, he even argued that the mistaken belief that animals can have conscious sensations is one of the worst obstacles to the progress of science and rationality.

In Descartes’ Meditations, he lays out the famous deceiving demon, remarkably similar to Avicenna’s Floating Man thought experiment. In the beginning of the work, Descartes says he won’t tell us about his first meditations, “for they are so abstract and unusual that they will probably not be to the taste of everyone”, a thought he might have kept to himself. Descartes argues that we all accept things that we believe to be certain, but sometimes these then turn out to be wrong. Therefore, we cannot use certainty as the sole criterion for truth. We have to separate out the categorically certain from the seemingly certain. Descartes says that it seems certain that he is sitting by the fire writing, but we can doubt this and believe that he is simply dreaming that he is Descartes by the fire.

In Descartes’ Meditations, he lays out the famous deceiving demon, remarkably similar to Avicenna’s Floating Man thought experiment. In the beginning of the work, Descartes says he won’t tell us about his first meditations, “for they are so abstract and unusual that they will probably not be to the taste of everyone”, a thought he might have kept to himself. Descartes argues that we all accept things that we believe to be certain, but sometimes these then turn out to be wrong. Therefore, we cannot use certainty as the sole criterion for truth. We have to separate out the categorically certain from the seemingly certain. Descartes says that it seems certain that he is sitting by the fire writing, but we can doubt this and believe that he is simply dreaming that he is Descartes by the fire.

He then uses the example of madmen who think that they are kings or that their bodies are made out of glass. Obviously, Descartes had some familiarity with madness and delusions, as did Avicenna. King Charles the Sixth (VI), also known as Charles the Mad, ruled France until 1422. He would sometimes forget his own name and run through his castle believing himself to be a wolf. Also, he was afraid of being touched by others, fearing that he was made of glass. When Descartes says that his audience is familiar with instances of insanity such as people believing they are made of glass, he is referring to Charles VI without mentioning him by name.

He then uses the example of madmen who think that they are kings or that their bodies are made out of glass. Obviously, Descartes had some familiarity with madness and delusions, as did Avicenna. King Charles the Sixth (VI), also known as Charles the Mad, ruled France until 1422. He would sometimes forget his own name and run through his castle believing himself to be a wolf. Also, he was afraid of being touched by others, fearing that he was made of glass. When Descartes says that his audience is familiar with instances of insanity such as people believing they are made of glass, he is referring to Charles VI without mentioning him by name.

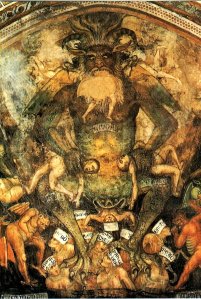

Let us remember Avicenna’s floating man thought experiment, in which he suggests that the reader imagine floating in a void and having all sensation, including of the body or senses, slowly taken away. What are you left with as the essential factor once the accidental sensual factors are removed? Our consciousness, awareness itself, stands alone as that which is evident in itself. Descartes proposes a very similar thought experiment, realizing that the self-evidence of awareness can undercut Pyrrhonian skepticism. He asks the reader to imagine that there is a deceiving demon that is trapping us in an illusion of a world, casting doubt on everything. What is the one thing that must be, even if Satan can deceive us such that two and three seem to equal five but in fact equal six? Consciousness, which Descartes lumps together with thinking, must exist even if it is deceived about everything else, and thus Descartes’ his famous line: “I think, therefore I am”.

Let us remember Avicenna’s floating man thought experiment, in which he suggests that the reader imagine floating in a void and having all sensation, including of the body or senses, slowly taken away. What are you left with as the essential factor once the accidental sensual factors are removed? Our consciousness, awareness itself, stands alone as that which is evident in itself. Descartes proposes a very similar thought experiment, realizing that the self-evidence of awareness can undercut Pyrrhonian skepticism. He asks the reader to imagine that there is a deceiving demon that is trapping us in an illusion of a world, casting doubt on everything. What is the one thing that must be, even if Satan can deceive us such that two and three seem to equal five but in fact equal six? Consciousness, which Descartes lumps together with thinking, must exist even if it is deceived about everything else, and thus Descartes’ his famous line: “I think, therefore I am”.

Where does the deceiving demon of Descartes come from? Descartes is writing in France in the late 1600s, two hundred years after the Cathars, a Gnostic and Manichean heresy that was being persecuted by the Church and their royal patrons in France in the 1400s. In the early development of Christianity, there were many competing schools with different interpretations of the life and teachings of Jesus. When the Roman Emperor Constantine called the council of Nicaea in 325 CE, there were some Christians, known as Gnostics, who argued that this world is ruled by Satan, who pretends to be God in the Old Testament (Jewish Torah), and we must break out of this deceptive dream. Constantine and the Church declared this heretical, arguing that the Old Testament is legitimate and that the world is ruled by God and administered by the Church. The Gnostics, expelled as heretics, likely saw the Church as a tool of Satan and cathedral of lies.

Where does the deceiving demon of Descartes come from? Descartes is writing in France in the late 1600s, two hundred years after the Cathars, a Gnostic and Manichean heresy that was being persecuted by the Church and their royal patrons in France in the 1400s. In the early development of Christianity, there were many competing schools with different interpretations of the life and teachings of Jesus. When the Roman Emperor Constantine called the council of Nicaea in 325 CE, there were some Christians, known as Gnostics, who argued that this world is ruled by Satan, who pretends to be God in the Old Testament (Jewish Torah), and we must break out of this deceptive dream. Constantine and the Church declared this heretical, arguing that the Old Testament is legitimate and that the world is ruled by God and administered by the Church. The Gnostics, expelled as heretics, likely saw the Church as a tool of Satan and cathedral of lies.

One branch of Gnosticism was Manichaeism, started by the Syrian Mani (200-276 CE) who claimed to be the final incarnation of Jesus, the Buddha Amitaba and the third Persian Zoroastrian Saoshyant, the messiahs of three great religious traditions. Manichaeism spread through Europe in 300 CE, and the Cathars were an offshoot that survived in France up until the persecutions of the 1400s. Thus, when Descartes asks if the world is a dream ruled by a demon and then concludes that it is not, he is entirely in line with centuries-old Catholic doctrine against the Gnostics and Cathars, as a demon could not keep us entirely in the dark and God does not completely deceive us in this world. Thus, for Descartes, we can know certain truth in the name of both science and religion.

There do seem to be universal truths such as 2 + 3 = 5, or a square always has four sides, both examples Descartes uses. However, as Descartes himself says, we can even imagine that these are delusions and that it could be someone extremely powerful who uses ‘industry’ to deceive us. Hence, we imagine that there could be a deceiving demon, or, as later philosophers who want to remove demons from the thought experiment would say, a mad scientist who has our brain in a vat, or, as the Wachowski siblings later staged it, the Matrix connecting us all in a false virtual-reality cyberspace. Because we are sure of this consciousness, Descartes argues that we are not in the power of something that completely lies to us, and then quickly, without much of a convincing argument, declares that we can trust that God is good, the world is not an illusion and that we can assume things that appear universal are certain, such as 2 + 3 = 5. Unfortunately, Descartes admits that we still must assume.

There do seem to be universal truths such as 2 + 3 = 5, or a square always has four sides, both examples Descartes uses. However, as Descartes himself says, we can even imagine that these are delusions and that it could be someone extremely powerful who uses ‘industry’ to deceive us. Hence, we imagine that there could be a deceiving demon, or, as later philosophers who want to remove demons from the thought experiment would say, a mad scientist who has our brain in a vat, or, as the Wachowski siblings later staged it, the Matrix connecting us all in a false virtual-reality cyberspace. Because we are sure of this consciousness, Descartes argues that we are not in the power of something that completely lies to us, and then quickly, without much of a convincing argument, declares that we can trust that God is good, the world is not an illusion and that we can assume things that appear universal are certain, such as 2 + 3 = 5. Unfortunately, Descartes admits that we still must assume.

Descartes begins his Discourse on Method, the mature statement of his philosophy as a system, with what seems like a sarcastic joke: Everyone must have reason, because even the hardest to please are pleased with the reasoning they already have. Descartes argues that all men have reason, the power to distinguish truth from error. He does not mention women or particular ethnic groups, but does say that reason distinguishes humans from brutes, all non-human animals. While we all have reason, we do not all use it in the same ways or to the same extent because we desire and fear different things.

Descartes says that he never considered himself the most talented mind, but he was fortunate enough to stumble onto a method of four principles for reaching truth through the power of reason and has reaped wonderful satisfaction from the clear and distinct ideas it has given him. First, never accept anything as true which is not clearly and distinctly known beyond all doubt, avoiding prejudice. Second, to divide problems into as many parts as needed to find a solution. Third, to start with the simplest and easiest and work step by step to the complex and difficult. Fourth, to consider each of the particular parts and the general whole to leave nothing out. He writes, “I gradually rooted out from my mind all the errors which had hitherto crept into it. Not that in this I imitated the skeptics who doubt only that they may doubt, and seek nothing beyond uncertainty itself; for, on the contrary, my design was singly to find ground of assurance, and cast aside the loose earth and sand, that I might reach the rock or the clay.”

Strangely, even though everyone possesses reason Descartes found college confusing and education without solid, absolute foundations, much as Russell, founder of Logical Positivism, found almost three hundred years later. Much like Russell, Descartes writes that “considering that of all those who have hitherto sought truth in the sciences, the mathematicians alone have been able to find any demonstrations, that is, any certain and evident reasons”, and so mathematics will serve as the foundations of true, pure reason, “adherence to the true order”, similar words Descartes uses to describe the Catholic Church.

Unlike Russell, an atheist who hopes for science to wholly replace religion, Descartes argues that mathematical reason proves God exists. Even though Descartes argues that our mind and reason is the only object that is independent and known in itself, he is moved to reason that there is a more perfect being that allows for our minds. “I found that the existence of the Being was comprised in the idea in the same way that the equality of its three angles to two right angles is comprised in the idea of a triangle, or as in the idea of a sphere, the equidistance of all points on its surface from the center, or even still more clearly; and that consequently it is at least as certain that God, who is this Perfect being, is, or exists, as any demonstration of geometry can be…Thus I perceived that doubt, inconstancy and sadness could not be found in God (whose existence has been established by the preceding reasonings).”

Of all occupations, Descartes decided none is better than philosopher, “devoting my whole life to the culture of my reason” and making as much progress towards truth as possible. It is a “source of satisfaction so intense” that a “more perfect or more innocent” profession, one that does as little wrong in the world as possible, cannot be enjoyed in this life other than philosophy. “I daily discovered truths that appeared to me of some importance, and of which other men were generally ignorant, the gratification thence arising so occupied my mind that I was wholly indifferent to every other object.” The “secret power of philosophers”, Descartes says, is they realize that the only thing that we truly possess and command is our own minds and reason, and so they devote themselves entirely to this rather than other objects.

Descartes & Objects of Thought

One of the “faculties of mind” that is central to Descartes’ thought about thought, mind and world is the part of our minds which grasps objects as particular things, independent of but necessary for perception, imagination, understanding and reasoning. This faculty, a part of our minds which interacts with other parts, as well as with other minds that share the same parts, is sometimes called intellect in translations of the work of ancient Greek and Indian philosophers, even though we use the word intellect to mean mind as a whole as well as reason in part. If I tell you that I will possibly, not certainly, eat an apple tomorrow, I can understand and refer to this apple, as can others, even if it turns out that I don’t eat an apple. This shows that objects of thought do not have to be true or existing, but can be possible, absent, or even impossible, and still understood and shared in the minds of many at once.

One of the “faculties of mind” that is central to Descartes’ thought about thought, mind and world is the part of our minds which grasps objects as particular things, independent of but necessary for perception, imagination, understanding and reasoning. This faculty, a part of our minds which interacts with other parts, as well as with other minds that share the same parts, is sometimes called intellect in translations of the work of ancient Greek and Indian philosophers, even though we use the word intellect to mean mind as a whole as well as reason in part. If I tell you that I will possibly, not certainly, eat an apple tomorrow, I can understand and refer to this apple, as can others, even if it turns out that I don’t eat an apple. This shows that objects of thought do not have to be true or existing, but can be possible, absent, or even impossible, and still understood and shared in the minds of many at once.

It is in the second and third Meditations that Descartes presents the something, a variable, unknown object, which can be grasped beyond perception and imagination, grasped by the mind, as the sort of mechanism which serves as foundation for his argument and positions. He asks, “Am I not at least something?” (p.18) The self, the world, mathematical objects, and God, remain somethings, objects of thought, which we can doubt, affirm, and postulate as possible. Descartes explicitly rejects Aristotle’s definition of man as “rational animal”, preferring to focus on the graspability of the object of the self by the mind as its own identical self rather than refer to anything outside the simple grasp of the object. This focuses on the existential and ontological nature of objects themselves, and not on the power of speech, imagination or associative representation to further complicate things. Rather, it is the simple grasp of objects by the mind, as an object itself, by which Descartes “defines” the mind:

It is in the second and third Meditations that Descartes presents the something, a variable, unknown object, which can be grasped beyond perception and imagination, grasped by the mind, as the sort of mechanism which serves as foundation for his argument and positions. He asks, “Am I not at least something?” (p.18) The self, the world, mathematical objects, and God, remain somethings, objects of thought, which we can doubt, affirm, and postulate as possible. Descartes explicitly rejects Aristotle’s definition of man as “rational animal”, preferring to focus on the graspability of the object of the self by the mind as its own identical self rather than refer to anything outside the simple grasp of the object. This focuses on the existential and ontological nature of objects themselves, and not on the power of speech, imagination or associative representation to further complicate things. Rather, it is the simple grasp of objects by the mind, as an object itself, by which Descartes “defines” the mind:

What about thinking? Here I make my discovery: thought exists; it alone cannot be separated from me. I am; I exist – this is certain. But for how long? For as long as I am thinking; for perhaps it could also come to pass that if I were to cease all thinking I would then utterly cease to exist. At this time I admit nothing that is not necessarily true. I am therefore precisely nothing but a thinking thing; that is, a mind, or intellect, or understanding, or reason – words of whose meanings I was previously ignorant. Yet I am a true thing and am truly existing; but what kind of thing? I have said it already: a thinking thing. (p.19)

What about thinking? Here I make my discovery: thought exists; it alone cannot be separated from me. I am; I exist – this is certain. But for how long? For as long as I am thinking; for perhaps it could also come to pass that if I were to cease all thinking I would then utterly cease to exist. At this time I admit nothing that is not necessarily true. I am therefore precisely nothing but a thinking thing; that is, a mind, or intellect, or understanding, or reason – words of whose meanings I was previously ignorant. Yet I am a true thing and am truly existing; but what kind of thing? I have said it already: a thinking thing. (p.19)

Descartes asks, “What else am I? I will set my imagination in motion,” but he fails to find anything in imagination, visual, tactile or otherwise, which further qualifies or defines the mind beyond the simply thinking thing, as an object which is capable of grasping objects:

Thus I realize that none of what I can grasp by means of the imagination pertains to this knowledge that I have of myself. Moreover, I realize that I must be most diligent about withdrawing my mind from these things so that it can perceive its nature as distinctly as possible.

But what then am I? A thing that thinks. What is that? A thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wills, refuses, and that also imagines and senses. (p.20)

But what then am I? A thing that thinks. What is that? A thing that doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wills, refuses, and that also imagines and senses. (p.20)

For Descartes, understanding and doubting are positive and negative states of thought, affirmed & denied are positive and negative states of speech which depend on corresponding forms of thought, and wills & refuses are corresponding states of emotion which similarly depend on forms of thought.

Descartes illustrates and furthers this minimal grasp with his example of heated wax, arguing that we certainly do not grasp the wax from perception of its physical properties (p.21), nor from our ability to imagine the possibilities of physical properties or their alteration (p.22), but rather, “through the mind alone.” He supplies the further illustration of men we can consider to possibly be automata, robotic machines, beneath their clothes as to why we cannot trust imagination or representation by speech as fundamental, compared to grasping objects as objects:

But meanwhile I marvel at how prone my mind is to errors. For although I am considering these things within myself silently and without words, nevertheless I seize upon words themselves and I am nearly deceived by the ways in which people commonly speak. For we say that we see the wax itself, if it is present, and not that we judge it to be present from its color or shape. Whence I conclude straightaway that I know the wax through the vision had by the eye, and not through an inspection on the part of the mind alone. But then were I perchance to look out my window and observe men crossing the square, I would ordinarily say I see the men themselves just as I say I see the wax. But what do I see aside from hats and clothes, which could conceal automata? Yet I judge them to be men. Thus what I thought I had seen with my eyes, I actually grasped solely with the faculty of judgment, which is in my mind... But indeed when I distinguish the wax from its external forms, as if stripping it of its clothing, and look at the wax in its nakedness, then, even though there can be still an error in judgment, nevertheless I cannot perceive it thus without a human mind. (p.22-23)

But meanwhile I marvel at how prone my mind is to errors. For although I am considering these things within myself silently and without words, nevertheless I seize upon words themselves and I am nearly deceived by the ways in which people commonly speak. For we say that we see the wax itself, if it is present, and not that we judge it to be present from its color or shape. Whence I conclude straightaway that I know the wax through the vision had by the eye, and not through an inspection on the part of the mind alone. But then were I perchance to look out my window and observe men crossing the square, I would ordinarily say I see the men themselves just as I say I see the wax. But what do I see aside from hats and clothes, which could conceal automata? Yet I judge them to be men. Thus what I thought I had seen with my eyes, I actually grasped solely with the faculty of judgment, which is in my mind... But indeed when I distinguish the wax from its external forms, as if stripping it of its clothing, and look at the wax in its nakedness, then, even though there can be still an error in judgment, nevertheless I cannot perceive it thus without a human mind. (p.22-23)

In the third of the Meditations, Descartes proceeds to evaluate the truth and falsity of his particular ideas, grasping each as an object, as he does the soul, God, wax and minds of clothed men, demonstrating that we can grasp objects independently of truth as we consider their truth, necessary for all practices of philosophy and debate. How else could we, as we do with fiction, suspend disbelief? To consider potential ideas, we must suspend both belief and disbelief, opening the possibility and consideration of both exclusive conditions at once. Descartes compares bare objects to chimeras, as a fictional beast we grasp independent of actual existence:

Now as far as ideas are concerned, if they are considered alone and in their own right, without being referred to something else, they cannot, properly speaking, be false. For whether it is a she-goat or a chimera that I am imagining, it is not less true that I imagine the one than the other. Moreover, we need not fear that there is falsity in the will itself or in the affects, for although I can choose evil things or even things that are utterly non-existent, I cannot conclude from this that it is untrue that I do choose these things. Thus there remains only judgments in which I must take care not to be mistaken. Now the principal and most frequent error to be found in judgments consists in the fact that I judge that the ideas which are in me are similar to or in conformity with certain things outside me. Obviously, if I were to consider these ideas merely as certain modes of my thought, and were not to refer them to anything else, they could hardly give me any subject matter for error. (p.25-26)

Now as far as ideas are concerned, if they are considered alone and in their own right, without being referred to something else, they cannot, properly speaking, be false. For whether it is a she-goat or a chimera that I am imagining, it is not less true that I imagine the one than the other. Moreover, we need not fear that there is falsity in the will itself or in the affects, for although I can choose evil things or even things that are utterly non-existent, I cannot conclude from this that it is untrue that I do choose these things. Thus there remains only judgments in which I must take care not to be mistaken. Now the principal and most frequent error to be found in judgments consists in the fact that I judge that the ideas which are in me are similar to or in conformity with certain things outside me. Obviously, if I were to consider these ideas merely as certain modes of my thought, and were not to refer them to anything else, they could hardly give me any subject matter for error. (p.25-26)

Just as Frege remarked (FA s.28) that we can understand atoms even as we imagine they are invisible, Descartes argues that our ideas of the sun can employ imagination resembling perception, but not always, and imagination can represent the same idea by resembling it in differing ways:

Just as Frege remarked (FA s.28) that we can understand atoms even as we imagine they are invisible, Descartes argues that our ideas of the sun can employ imagination resembling perception, but not always, and imagination can represent the same idea by resembling it in differing ways:

And finally, even if these ideas did proceed from things other than myself, it does not therefore follow that they must resemble those things… For example, I find within myself two distinct ideas of the sun. One idea is drawn, as it were, from the senses… By means of this idea the sun appears to me to be quite small. But there is another idea, one derived from astronomical reasoning, that is, it is elicited from certain notions that are innate in me, or else is fashioned by me in some other way. Through this idea the sun is shown to be several times larger than the earth. Both ideas surely cannot resemble the same sun existing outside of me; and reason convinces me that the idea that seems to have emanated from the sun itself from so close is the very one that least resembles the sun. (p.27)

Having evaluated the truth and falsity of ideas independently in the third of the Meditations, in the fourth Descartes finds the self and soul to be essentially and exclusively a logical object, in a kind of thought space that Wittgenstein describes in the Tractatus rather than in any sort of physical space, grasping thoughts, and this itself demonstrates the grasp of objects by the mere object of thinking mind:

Having evaluated the truth and falsity of ideas independently in the third of the Meditations, in the fourth Descartes finds the self and soul to be essentially and exclusively a logical object, in a kind of thought space that Wittgenstein describes in the Tractatus rather than in any sort of physical space, grasping thoughts, and this itself demonstrates the grasp of objects by the mere object of thinking mind:

The upshot is that I now have no difficulty directing my thought away from things that can be imagined to things that can be grasped only by the understanding and are wholly separate from matter. In fact the idea I clearly have of the human mind – insofar as it is a thinking thing, not extended in length, breadth or depth, and having nothing else from the body – is far more distinct than the idea of any corporeal thing. (p.35)

The upshot is that I now have no difficulty directing my thought away from things that can be imagined to things that can be grasped only by the understanding and are wholly separate from matter. In fact the idea I clearly have of the human mind – insofar as it is a thinking thing, not extended in length, breadth or depth, and having nothing else from the body – is far more distinct than the idea of any corporeal thing. (p.35)

Descartes continues to argue for the clarity and distinction of non-corporeal objects grasped by the mind, including the self, God, and mathematical truths, as these objects, abstracted from entanglements with perception, imagination and communication, are clearer than those entangled with experience and imagination, as understandings beyond perception, imagination and communicative representation.

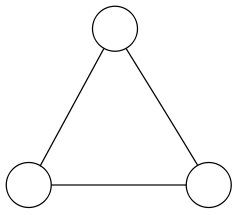

In the sixth and final of the Meditations, Descartes further illustrates objects grasped beyond perception, imagination and communication by comparing an abstract triangle with the further geometric illustrations of the pentagon and chiliagon, a thousand sided figure. For Descartes, we need not bother to imagine, or effectively imagine a circle with a crinkled perimeter, and need not articulate a thousand sides in our imagination to grasp the chiliagon. Do we trust our imaginations to create exactly a thousand sides to it? It is interesting to note that we don’t feel the need to check, as long as we grasp it as an object. Descartes says:

In the sixth and final of the Meditations, Descartes further illustrates objects grasped beyond perception, imagination and communication by comparing an abstract triangle with the further geometric illustrations of the pentagon and chiliagon, a thousand sided figure. For Descartes, we need not bother to imagine, or effectively imagine a circle with a crinkled perimeter, and need not articulate a thousand sides in our imagination to grasp the chiliagon. Do we trust our imaginations to create exactly a thousand sides to it? It is interesting to note that we don’t feel the need to check, as long as we grasp it as an object. Descartes says:

To make this clear, I first examine the difference between imagination and pure intellection. So, for example, when I imagine a triangle, I not only understand that it is a figure bounded by three lines, but at the same time I also envisage with the mind’s eye those lines as if they were present and this is what I call “imagining.” On the other hand, if I want to think about a chiliagon, I certainly understand that it is a figure consisting of a thousand sides, just as well as I understand that a triangle is a figure consisting of three sides, yet I do not imagine those thousand sides in the same way, or envisage them as if they were present. And although in that case – because of force of habit I always imagine something whenever I think about a corporeal thing – I may perchance represent to myself some figure in a confused fashion, nevertheless this figure is obviously not a chiliagon. For this figure is really no different from the figure I would represent to myself, were I thinking of a myriagon or any other figure with a large number of sides. Nor is this figure of any help in knowing the properties that differentiate a chiliagon from other polygons… At this point I am manifestly aware that I am in need of a peculiar sort of effort on the part of the mind in order to imagine, one that I do not employ in order to understand. This new effort on the part of the mind clearly shows the difference between imagination and pure intellection. Moreover, I consider that this power of imagining that is in me, insofar as it differs from the power of understanding, is not required for my own essence, that is the essence of my mind. (p.47-48)

To make this clear, I first examine the difference between imagination and pure intellection. So, for example, when I imagine a triangle, I not only understand that it is a figure bounded by three lines, but at the same time I also envisage with the mind’s eye those lines as if they were present and this is what I call “imagining.” On the other hand, if I want to think about a chiliagon, I certainly understand that it is a figure consisting of a thousand sides, just as well as I understand that a triangle is a figure consisting of three sides, yet I do not imagine those thousand sides in the same way, or envisage them as if they were present. And although in that case – because of force of habit I always imagine something whenever I think about a corporeal thing – I may perchance represent to myself some figure in a confused fashion, nevertheless this figure is obviously not a chiliagon. For this figure is really no different from the figure I would represent to myself, were I thinking of a myriagon or any other figure with a large number of sides. Nor is this figure of any help in knowing the properties that differentiate a chiliagon from other polygons… At this point I am manifestly aware that I am in need of a peculiar sort of effort on the part of the mind in order to imagine, one that I do not employ in order to understand. This new effort on the part of the mind clearly shows the difference between imagination and pure intellection. Moreover, I consider that this power of imagining that is in me, insofar as it differs from the power of understanding, is not required for my own essence, that is the essence of my mind. (p.47-48)

Thus, through the full distance of the Mediations, Descartes argues (Meditations 1) objects beyond sight and touch, such as God and the mind/soul, are the most fundamental to grasp, as we can doubt all we sense, imagine and explain with speech. The self (Meditations 2) is nothing but a something, an object of thought, which itself thinks, grasping objects, such as itself, whether or not they are perceived, imagined or understood with practices of speech. By suspending belief and disbelief (Meditations 3) we can clearly focus on the forms thoughts take “beneath the clothes” of perception, imagination and communication which vary beyond the grasp which transcendentally supplies all these practices of thought their coherence. The mind (Meditations 4) is merely an object which grasps other objects, as well as other minds which themselves grasp objects beyond our own subjective grasp. The triangle (Meditations 5), just like the imaginable pentagon and unimaginable chiliagon (Meditations 6) is, just like the mind, an object we grasp and share in grasping whether or not we perceive, imagine, communicate or do so as others who share our grasp do.

Thus, through the full distance of the Mediations, Descartes argues (Meditations 1) objects beyond sight and touch, such as God and the mind/soul, are the most fundamental to grasp, as we can doubt all we sense, imagine and explain with speech. The self (Meditations 2) is nothing but a something, an object of thought, which itself thinks, grasping objects, such as itself, whether or not they are perceived, imagined or understood with practices of speech. By suspending belief and disbelief (Meditations 3) we can clearly focus on the forms thoughts take “beneath the clothes” of perception, imagination and communication which vary beyond the grasp which transcendentally supplies all these practices of thought their coherence. The mind (Meditations 4) is merely an object which grasps other objects, as well as other minds which themselves grasp objects beyond our own subjective grasp. The triangle (Meditations 5), just like the imaginable pentagon and unimaginable chiliagon (Meditations 6) is, just like the mind, an object we grasp and share in grasping whether or not we perceive, imagine, communicate or do so as others who share our grasp do.