For this lecture, please read Plato’s Republic Book 4 & Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Books 1-3.

The photo above is from Athens today, where the site of the Lyceum, where Aristotle taught for many years, sits close to the presidential palace of Greece, effectively their White House, where the president of Greece lives. Notice the Greek Orthodox church sitting in the back.

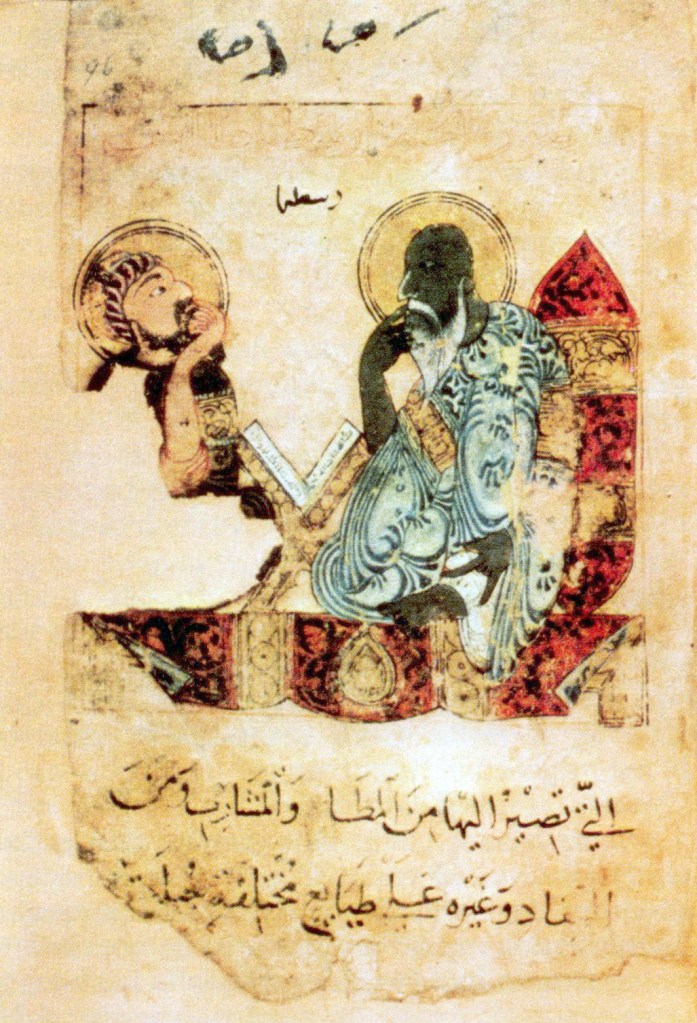

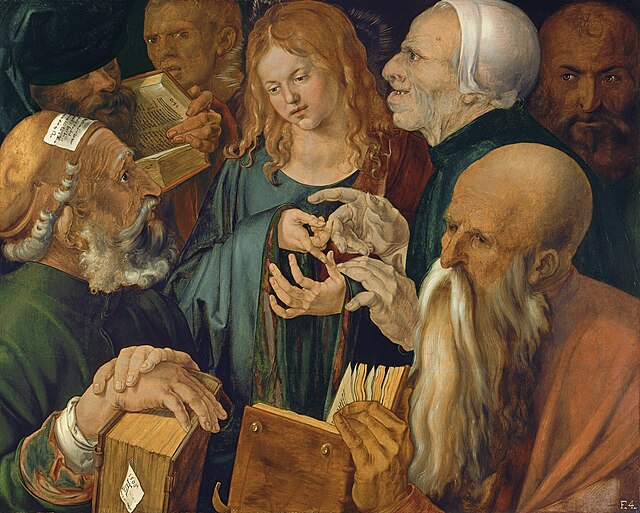

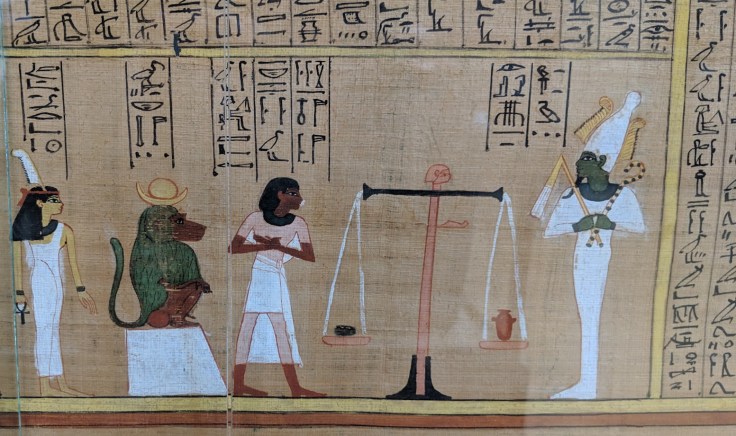

In this Islamic image to the left, the great caliph and patron of philosophy, science and the arts, Al-Mamun dreamed that he spoke with Aristotle. Both are portrayed with halos, the fire of the mind and insight, Aristotle is portrayed as much darker in skin than the Muslim ruler, and there is a Chinese-style book that folds in the middle which did not exist in Aristotle’s time but still does in our own, for now. This is because Aristotle was revered by Muslim scholars, philosophers and logicians, as well as many from the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism and Christianity.

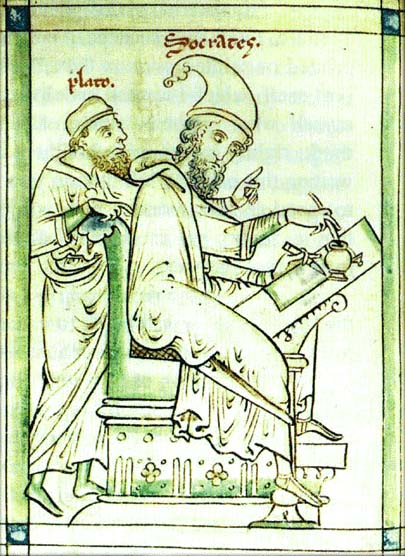

Socrates (469 – 399 BCE) is a very famous yet controversial and obscure figure. Like many great thinkers of the ancient world, he did not write his own thoughts down but taught others. It was Plato and another philosopher and historian named Xenophon (not Xenophanes, yet another philosopher) who wrote about Socrates and his teachings after his death. It is generally accepted by scholars today that Plato’s early dialogues are one of the best sources for understanding Socrates and his ideas, but in Plato’s later dialogues Socrates turns into a mouthpiece for Plato’s own ideas, including those he borrowed from Pythagoras and Parmenides. Plato was a playwright who wrote several unpopular plays before writing the dialogues between Socrates and his students that became celebrated as central works of ancient Greek philosophy. While Plato never appears in his plays himself, he does put his own family members in roles, and has characters mention him as a young devoted follower of Socrates. Originally these dialogues would have been staged as plays, with the characters likely wearing masks, much as drama had been performed earlier in Egypt, with Greek drama influenced by the comedies and tragedies of the Egyptians and others. We do not know how popular Plato’s plays featuring Socrates were on the stage, but as texts Plato’s plays became the most famous and well studied works of ancient Greek philosophy, particularly through their impact in the Abrahamic world among Jewish, Christian and Muslim philosophers, logicians and scholars.

Originally, Socrates questioned everyone to show that we know very little and it is the job of the philosopher to show this to people. He would argue with others, including famous thinkers and sages, who believed that they possessed certain truth and point out the contradictions in their reasoning. This is much like Heraclitus telling us to beware of experts and being seduced into thinking that one school of thought or perspective is simply correct but instead continue to investigate the self and world as both have no limit to their depth or the things we can learn. While Socrates did not put forward views of his own but rather attacked others to show that human beliefs are imperfect and incomplete, he believed like Xenophanes and Heraclitus that there is a true good we should strive for through investigation even if we never come to have a complete understanding of it.

In Plato’s later dialogues Socrates argues for a view much more like that of Pythagoras and Parmenides, that there is one unchanging reality above the temporary perceivable world and it is the job of the philosopher to seek and understand this eternal reality. Plato uses Socrates to teach his own increasingly Pythagorean view that there are unchanging and eternal form of things in the heavens and only the educated and the persistent come to see and understand these forms. This later Platonic Socrates argues that there is knowledge above and separate from opinion, and that the truth is eternal and unchanging. However, unlike Parmenides and Zeno but like Pythagoras, Plato’s later Socrates believes that we can know the eternal truth as having a proportional form. The ‘form of the good’ is eternal, so it does not change with time, but it does have a distinct shape much as Pythagoras discovered via mathematics.

Socrates’ career as a philosopher began when his friend Chaerephon went to the Oracle of Delphi to ask if anyone was wiser than his friend Socrates. Socrates, with characteristic modesty, protests that this was a very crass question to ask of the great oracle. The oracle replied to Chaerephon that no one was wiser than Socrates. Upon hearing this, Socrates says, with either genuine or false modesty, he was very troubled by this because he did not believe that he was very wise at all and this would mean that humanity is quite ignorant. He decided that he needed to determine if what the oracle said was in fact true, and so he began to wander and debate others, seeking someone wiser than himself.

Socrates felt that he knew nothing, but as he questioned the experts of Athens he came upon a horrible discovery and paradox. The experts believed themselves to be wise and possess great knowledge, but when questioned it turned out they knew very little. Socrates knew that he himself knew nothing. Therefore, Socrates discovered that he was wiser than the experts because he knew that he knew nothing, while the experts knew nothing but thought that they knew a great deal. Humble and modest Socrates was aware that mortal humans know nothing, but the philosophers, politicians, artists and warriors were unaware of this great equality they shared with Socrates. The ignorance of Socrates was thus the greatest wisdom in all of Athens. It is certainly true that the more one knows, the more one knows there is an endless amount to know and that we are all quite equal in knowing very little even when we know a great deal. There is another paradox here: the more one surpasses others in wisdom, becoming different, one identifies with them more, seeing the common similarity. Love and wisdom are complimentary.

Socrates argued that one should accept one’s own ignorance and the guidance of the world through intuition. He believed that he had a spirit, a ‘daemon’ in the Greek, a word which became “demon” as Christianity replaced the polytheism and spirits with monotheism and angels. This spirit was much like what we would call a conscience, a word which means “co-seeing” or seeing along with, an intuition that one should or should not do a particular thing, something Christians identified with angels sitting on shoulders just as ancient Greeks did with spirits. Intuition has been understood as listening to one’s own heart, recalling the heart-guided individual of the middle kingdom period of Egypt. Intuition is thus often understood to be paying attention to one’s own feelings and emotions rather than ignoring them, and allowing them to guide us when we do not have a conscious, logical plan as to what we must do, but we need not put intuition on the side of emotion versus reason if we understand the two to be interwoven and that intuition involves slowing down and paying attention to what our minds understand but can push to the periphery and out of immediate awareness. Socrates did not say his guiding spirit, his daemon, was an emotional and irrational creature, but rather a higher sort of mind, a spirit above his own spirit.

Socrates says that his daemon told him to stay out of politics. Good advice, seeing as how his death was quite political. Not only did politics get Socrates killed in spite of this, but Plato has Socrates get increasingly political in his later dialogues, particularly in the Republic where Socrates debates the best form of the city. The Apology is Plato’s account of Socrates’ speech he gave in his own defense at his trial. Xenophon and others wrote their own accounts of Socrates’ defense, though little of these other accounts survived. While our word ‘apology’ means an admission of guilt and wrong, originally the word applied to any argument or explanation of one’s actions, regardless of how right or wrong one believed these actions to be. Socrates’ apology is not an “apology” the way we use the term today, but rather what we might call today a non-apology, as he explains to the Athenian assembly why he was not wrong but was doing a great service to Athens by forcing them to examine their lives and beliefs critically.

In his rounds of Athens, searching for wisdom among the Athenians and not finding much of it, Socrates had acquired followers, many of whom were young and critical of Athenian society. These students began, like Socrates, to question their elders as well as the traditions and institutions in which the elders were involved. These included both the Homeric culture and the political organization of the state. After this had increasingly annoyed the traditional and the powerful for a good length of time, riots broke out that may or may not have included some of Socrates’ students. These riots destroyed temples and statues of the Homeric gods. Blaming Socrates, the Athenian assembly accused him of impiousness towards the old gods, believing in new gods, and leading the youth astray. These “new gods” were likely the abstract ‘good’ that Socrates believed should be pursued, as well as the daemon, spirit or conscience Socrates conversed with to seek the true and the good.

As the Apology begins, Socrates begins by saying that he knows nothing for certain, and knows that he knows nothing. Note that this is a good defense against the charges of holding heretical views and leading others to heretical views different from the traditional views, as Socrates does not have particular views, nor does he know the traditional views are false. Socrates says he is not a good speaker, unlike the great orators of Athens who are good at swaying others to their own opinions, and asks the assembly to judge him not by his skill with words but by the truth. This is, of course, a rhetorical tactic similar to the infamous “Now, I’m just a simple country lawyer” approach used on the TV show Matlock and in the Saturday Night Live skit Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer, in which Phil Hartman says, “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I’m just a caveman…Your world frightens and confuses me…but what I DO know, is my client is entitled to a large cash settlement”. Apparently, Socrates’ knowing that he doesn’t know makes a decent defense in court. Confucius was also very critical of those who can speak well with rhetoric, arguing that speaking well without being good is a serious problem in society.

In terms of knowledge, Socrates is a mere mortal. In terms of wisdom, Socrates argues for the view of the gods. This is quite similar to Heraclitus, who said that our language sounds like baby-talk to the cosmic powers, and the wisdom of the wisest man sounds like the grunts and cries of an ape. Socrates, like Heraclitus, suggests that even as a mortal ape, far beneath the cosmic powers, we are indeed of striving for and achieving wisdom, even if this wisdom will never rival that of the cosmos. Socrates tells the Athenians that they are far more concerned with acquiring wealth than wisdom, and that there is nothing better for Athens then his taking up the role of the horsefly, the annoying pest that stings the horse and forces it into action.

The Athenian assembly votes, and Socrates is found guilty by a slight majority. The assembly was said to be composed of about five hundred, and Socrates says in response that only thirty votes would have changed the verdict, making the tally about 280 voting guilty, 220 voting not guilty. Instead of pleading for mercy before he is sentenced, Socrates suggests to the assembly that he should be given free meals for life in the main council building, an honor reserved for military heroes and champion athletes. Diogenes Laertius claims that this angered the assembly, and that more chose to vote for a death sentence than had initially voted for Socrates’ guilt. Socrates tells both those who voted against him and those who voted in his favor that he did the right thing even in the face of death, which is the best that can be done. Socrates speculates that death may very well bring freedom from all desires and discomforts, and that he may be able to meet great souls such as Hesiod and Homer, with whom he may continue to question and practice philosophy. We can imagine Hesiod and Homer looking with concern and fear as Socrates joins them in the Elysian Fields beyond, as now he gets to annoy them with endless questions and contrary arguments.

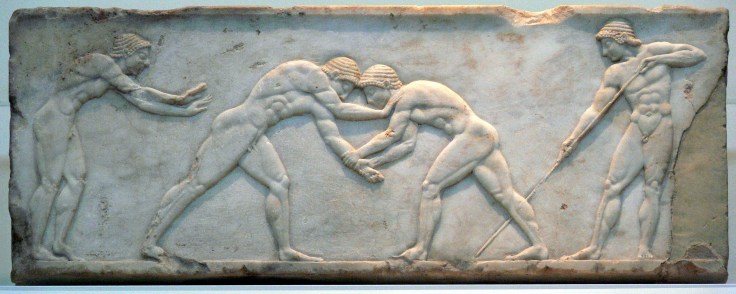

Plato (428 – 348 BCE) was actually named Aristocles, but according to the story his wrestling instructor named him Platon or ‘Broad’ because he had a wide figure and wrestling stance. Plato was known to have a wide and thus broad breadth of knowledge covering all subjects of ancient thought and might have acquired the nickname in this way. Plato’s father died when he was young, and his stepfather became the Athenian ambassador to the Persian royal court. Persia was a great source of ancient world cosmology at the time, and Zoroastrianism, Persia’s solar monotheism, would be a major influence on the Abrahamic religions just as Plato himself would. The three wise men who visited baby Jesus are presented by the text as Persian Zoroastrians, who are following the stars and looking for the incarnation of their monotheistic god who will become the savior of the world, known as the saoshyant in Persian and messiah in Hebrew. Long after his attempts to become an established playwright, after his dialogues about Socrates had gathered some fame, Plato founded his Academy in 385 BCE, an open area near a sacred tree grove where he, his students and other lecturers would teach and debate matters of philosophy and cosmology.

Before we cover Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle’s central work on ethics, it is important to look at Book IV of Plato’s Republic (between 435c and 441c) as it is there that Plato has Socrates argue that there are three parts to the human soul, central to the Nicomachean Ethics. In the late dialogues, believed to have been written about 360 BCE, Socrates was no longer sharing much of the conversation with other debaters, but dominates the texts with monologues that are now Plato’s own Pythagorean and Parmenidean views of the eternal and unchanging form that is the hidden source of the mortal and temporary. Plato believed that Heraclitus was right about the world below, but that Heraclitus was overall wrong, and Pythagoras right about the eternal world above, the unchanging model, form, order and cause of the ever-changing world below. The image to the right is a fragment of Plato’s Republic found on a papyrus scroll.

In Book I of Plato’s Republic, we find Socrates debating with his fellow Athenian aristocrats at a house gathering on the nature of virtue, justice and the Good itself. After Socrates shoots down the views of others, Thrasymachus is irritated with Socrates’ incessant questioning, and demands that Socrates give his own account of what justice is. Socrates doesn’t, and instead asks Thrasymachus to give his own views, and Thrasymachus argues that justice is “the good of the stronger”. Athens had been conquered and reconquered by the Persians, just like the city states of Ionia such as Heraclitus’ Ephesus, and many rulers and forms of government had come and gone. Thrasymachus, like Socrates, does not claim to know what the good is in and of itself, but argues that the powerful get to impose their own views on the people as to what is good and what is bad, practicing their own form of justice as they see fit.

While this is similar to Socrates’ own position, not claiming to know the form in itself, it is quite pessimistic, skeptical of striving for good. Socrates believes that there is such a thing as good, virtue and justice, even if we mortals do not ever understand it entirely. Thrasymachus does not explicitly argue that there is no good in itself to strive for, but his relativistic position is pessimistic rather than optimistic. A third interlocutor, Glaucon, joins Thrasymachus and similarly argues that without threat of punishment, no one would do good. Socrates argues against them that the strong will corrupt themselves if they only act for their own interests and not for the good of the whole. Thrasymachus leaves, angered and unconvinced by Socrates’ arguments. This is the end of Book 1. Nothing has been resolved, and everyone, including Socrates, is unsatisfied with the results of the debate so far.

As Book II opens, Glaucon challenges Socrates to prove that justice is better than injustice. Since injustice seems so attractive to so many, why would people do what is just if they could do injustice without punishment? Socrates says to the remaining two that he did not feel he had convincingly refuted Thrasymachus, and that perhaps they should continue to debate to figure out what justice actually is. Plato, as his character Socrates, now argues for an eternal form of the Good over the world of many temporary beings and desires. Socrates argues that first they must construct the ideal or just city, and this will show how the ideal or just individual should be.

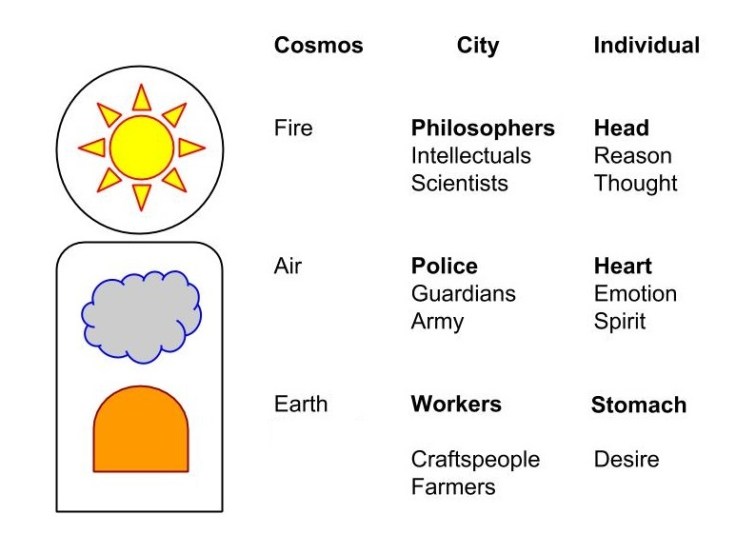

Essentially, the just city is a threefold caste system, identical in many ways to the Hindu caste system of India. Socrates first asks us to imagine a city ruled by desire, but devoid of courage or wisdom. Clearly, this would not be a just place, and everyone would grab for themselves and the city would fall to destruction. Socrates adds the police (also translated as ‘guardians’, but because the Greek word for city is polis, these guardians are quite literally the ‘police’). The police must keep their own desires in check, and be courageous. However, mere courage is not enough for the just ruling of a city. Lastly, Socrates adds the philosophers (the equivalent of priests, intellectuals and scientists), to provide the wisdom to lead the police, who keep the common people safe from outsiders as well as themselves.

This threefold division corresponds to the physical human being and the cosmic being. The head is fire as an element, reason, thought and consciousness in the individual, and the ruling philosopher kings in the city. The heart or chest is air as an element, spirit, breath and courage in the individual, and the police or guardians in the city. The hands and stomach is earth as an element, desire, craving and thirst in the individual, and workers, farmers and craftspeople in the city. Socrates also frames this in terms of the individual person. If one was thirsty for water, but one would lose honor or be poisoned by drinking, one’s courage or wisdom would be right to keep the desire in check. Similarly, if one wanted to go to war to gain honor, but it was unwise, one’s wisdom would be right in keeping one’s courage in check. Just as the head tells the heart and lungs what to do, and these regulate the rest of the body, in the good individual wisdom and reason rule over courage and spirit, which regulates desire and hunger.

Socrates argues that the ruler who grabs for themselves will not be happy, filled with “horrid pains and pangs”, and will physically and mentally fall apart. This tyrant will never “taste true freedom or friendship”. Because this tyrant’s rule is not in tune with the order of the cosmos, it will not stick and will fall apart just like the rule of many tyrants had recently in ancient Athens of Plato’s day. Similarly, if everyone shares everything in common, there will be greater justice and less selfishness. In the same way, if you put your desires and appetites in check with your feelings, and your feelings in check with your reason, you will be a well ordered soul and individual. This is Socrates’ ultimate and definite answer to Glaucon’s challenge. Glaucon and Adeimantus are both entirely convinced, and proclaim Socrates to have indeed given us the recipe for the just city as well as the good individual.

Socrates argues, and they agree without much of a fight, that if they separate out the police and train them as best as can be, and then take the philosophers out of the police and educate them as best as can be, this will create as little injustice as possible. There is the simple belief that the order itself will generate justice throughout the whole. Plato elsewhere argues that this is why the Egyptians in Thebes elevated priests as a class who ruled overall, and that Athens should be more like Egypt. He says they should imitate Sparta as well in separating out the warriors.

Before passing on from Plato to Aristotle, it is important to mention Plato’s “noble lie”, how it relates to the Plato’s three-part division within three-part division of the self, city and cosmos, and how it contradicts Kant’s morality, which we will study, as Kant’s central example of morality is never lie. Unfortunately, Plato’s Cave, one of his most memorable ideas, found in his Republic, is itself a rationalization and explanation of how we need to lie to keep society in its proper structure.

Socrates argues that in the ideal republic each person is best suited to one thing, and should be assigned this one job. If people do more than one job, they will not be able to do this one job as best as they can. He argues that we will lie to the people, tell them the ‘noble lie’ of a Phoenician story, that people were born from the earth and there are three races of people because the metals of gold, silver and bronze flow in their veins. Note that these are the three metals of the Olympic games, gold as first place, silver as second, and bronze as third. Why tell the lie, that there are gold, silver, and bronze people, if we are striving for ideal good and justice? Because the common people will not understand and grab for themselves, very much Plato’s opinion of the brief period of Athenian democracy. If you tell the truth to everyone, they will not believe you and try to destroy you as the assembly did Socrates when he asked them to put their desires in check with superior wisdom.

After being questioned about lying for the purpose of the good and justice, Socrates says that this is best explained with an analogy, the famous Allegory of the Cave. Imagine, Socrates asks, that everyone is chained in a dark cave, watching shadows of puppets carried before a fire at the mouth of the cave. The people think that the shadows are reality, the real things. The one who escapes, breaking the bondage of appetites and earthly things, first sees that the shadows are shadows of puppets, and sees the fire that casts the shadows. This draws the seeker to the mouth of the cave. Coming out of the cave and past the small fire, the seeker is at first blinded by the sunlight, but then sees real things outside of the cave and realizes that the puppets were just poor copies of the real things casting shadows that were shaped like real things. The seeker now has knowledge and the wisdom to see the difference between opinion (the shadows) and knowledge (the real things that the shadows imitate). While Heraclitus said there is no limit to wisdom, Plato has marked the limit as the mouth of the cave, the line between the mortal and eternal, between the assembly and Socrates himself. Keep in mind for Kant, that Kant argues that one must never lie for any utilitarian reason or consequence, and should certainly disagree with Plato that a lie can hold society together. However, Kant, like Aristotle, seems to be quite silent about this problem in Plato, and Kant may not be consistent on this himself.

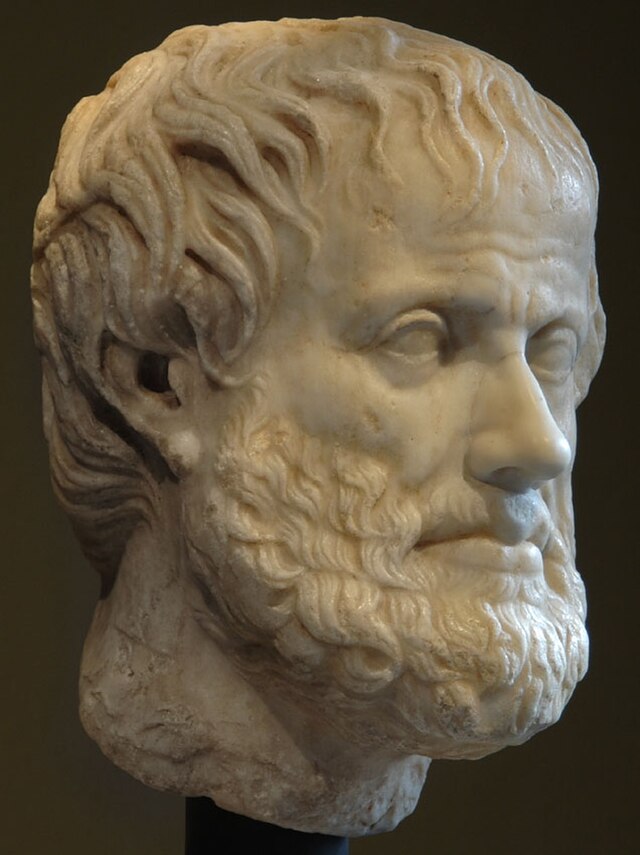

Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE), the most famous of Greek philosophers along with his teacher Plato and Plato’s teacher, Socrates, was born in Stragira, north of Athens. Aristotle’s father, Nicomachus, was the personal physician of Amyntas, King of Macedon. Aristotle also named his son Nicomachus, which is where the title of the Nicomachean Ethics takes its name. Later, Aristotle would become the tutor and advisor to Alexander the Great, the Macedonian monarch following his father Amyntas. Not much is known about Aristotle’s early life, and we do not know if Aristotle read Plato or other Athenian philosophers in Stragira, but when he was old enough, Aristotle traveled to Athens to join Plato’s Academy, where Plato had acquired a reputation for education. Aristotle studied with Plato for twenty years until Plato’s death in 347 BCE. Tradition has it that the Academy was taken over by Plato’s nephew Speusippus even though Aristotle was more qualified, possibly because Aristotle had come to disagree with Plato’s theory of ideal forms, and so Aristotle left. Aristotle was also never a citizen of Athens, always considered a foreigner and thus a barbarian by many prominent Athenians.

Aristotle traveled and studied in Ionia and Asia before King Philip of Macedon invited him to tutor his young son Alexander, thirteen at the time, who would go on to conquer and unify ancient Greece within his briefly unified empire along with Egypt and Persia. Aristotle also tutored Ptolemy and Cassander, who after Alexander’s death would take over parts of his divided empire. Aristotle founded his school in Athens in 335 BCE, holding meetings of his students at a public gymnasium named the Lyceum after a form of Apollo as a wolf god. The Lyceum had seen earlier philosophers give public talks, including Socrates and Plato, and it continued to be the meeting place for followers of Aristotle until Athens was sacked by the Romans 250 years later. The followers of Aristotle became known as the Peripatetics, the “Walk-about-ers”, as Aristotle enjoyed walking as he lectured, taught and answered questions. In the mornings, he would walk with a select number of advanced students in detailed, advanced seminars, and then in the evening give general talks open to any who would gather. A study at Stanford has shown that if one wants to retain knowledge through study, one should sit, but if one wants to stimulate critical and creative thinking, walking outside is best.

After Alexander died, Aristotle feared being killed by the Athenians as he was not only a barbarian foreigner and a Macedonian but the tutor of Alexander, who was not loved by most Athenians as their foreign conqueror. After Aristotle was accused publicly of impiety towards the gods, showing little in Athens had changed since the death of Socrates, Aristotle left Athens saying he would not allow the Athenians “to sin against philosophy twice”, recalling the death of Socrates due to similar charges. Aristotle, like his teacher Plato “the broad”, wrote on a great number of subjects. Many of his writings are now lost, and scholars debate which of his works are his own or the notes of his students. Diogenes Laertius wrote in Roman times about the work of Aristotle, though none of the works he mentions are known today. It is also possible that many of the texts we have are lecture notes, either Aristotle’s or his students’, and may not have been intended to stand as texts in their own right.

While some have called Aristotle a materialist, like Plato he believed that the idea and form of a thing is superior to the crude material, but unlike Plato he put emphasis on the lower, material part of things as also essential to what they are, famously captured in the center of the School of Athens painting by Rafael with Plato pointing to the heavens and Aristotle putting his hand over the earth below. If we could hear Aristotle talk, he would be telling Plato that material is the body of form, which is the mind, so the material is inferior to form, but also important and essential to form itself. Like Plato, Aristotle believed that the form or idea of a thing was its higher essence and being. The material out of which it was composed was temporary, less defined and definite as the form. For instance, if we build a building, our idea of the building’s form is more durable than the material, no matter how strong, out of which we build the building.

In his Posterior Analytics, a work on logic, Aristotle says that Plato’s forms, as forms in-themselves, are irrelevant for study. Because of this passage and others, Diogenes Laertius said that Aristotle was the foal who kicked his mother, as he departed from the doctrines of his teacher, Plato. However, Aristotle praised Plato himself, saying that Plato was, “unsurpassed among mortals, (and) has shown clearly by his own life and by the pursuits of his writings that a man becomes happy and good simultaneously”.

For several centuries following the work and schools of Plato and Aristotle, the Neoplatonists studied the works of both and assumed them to be harmonious and complementary. Plato was the authority of the intelligible world above, and Aristotle the authority of the sensible world below. This is reflected in the famous painting of Raphael, The School of Athens, with Plato and Aristotle at the center of the crowd, with Plato pointing to the heavens above and Aristotle extending his palm over the world below. Another important difference that put Plato over Aristotle in the Abrahamic world among Christians and Muslims is that Aristotle rejected the immortality of the soul, which Plato put at the center of his own ethics and psychology. Plato argued for reincarnation, and that our souls become higher or lower animals based on our actions, much like found in Hindu and Indian thought.

Aristotle’s understanding of the relationship between animals and humanity is central to his psychology, his logic, and also his ethics. He follows and employs Plato’s three-part division of the soul to argue that we alone are the rational animal, sharing passion, emotions and imagination with beasts, but not reason. Aristotle argues, in his works on logic and ethics, that we must grasp universals with reason to understand philosophy, science, logic and ethics, and this is our unique purpose as humans we must fulfill to be truly thriving, and thus the goal of his ethics for us overall. Oddly, like Plato, Aristotle did not grant most of humanity the ability to reason, such that most of humanity is not capable of thriving in our unique difference and purpose. For instance, Aristotle argued that German tribes do not take slaves, not do they put men in charge of women, and so Germans are barbarians who do not put the rational over the irrational, the free over slaves and men over women, which makes the Germans merely capable of being irrational slaves themselves.

Aristotle’s psychology is primarily found in his De Anima, “On the Soul”, one of the most important works of Aristotle for Christians and Muslims along with his works on logic and ethics. Aristotle, like Socrates in Plato’s Republic and the Pythagorean Timaeus of Plato’s Timaeus, argued that we have three parts to the soul, a lower vegetative appetite, an emotional spirit, and a rational mind. The rational mind is the most perfect and highest manifestation of the body. Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle argues that each of the three parts of the soul can be virtuous in their own way. The lowest center of desire, situated in the stomach, is virtuous when it promotes bodily health, what Aristotle calls nutritional virtue. The second center of spirit, situated in the chest, is virtuous when it promotes discipline and justice, what Aristotle calls moral virtue. Finally, the highest center of reason, situated in the head, is virtuous when it promotes study, investigation and contemplation, what Aristotle calls intellectual virtue. Aristotle believes that intellectual virtue leads to moral virtue, and moral virtue leads to nutritional virtue. When we are wise, we are moral, and when we are wise and moral, we are healthy. When we are unhealthy it is because we are undisciplined, and when we are undisciplined it is because we are unwise. A healthy person may not be wise or disciplined, like a talented artist who is neither courageous nor wise, in which case they will likely not remain healthy or talented for long. Similarly, a spirited and disciplined person may be healthy but not be wise, like an athlete or warrior who does not consider the larger picture before acting, in which case they will likely not remain disciplined or healthy for long.

For Aristotle, soul is the living, mortal force which makes us and animals alive. Soul is invoked by Aristotle to explain two things, capacity for movement, and capacity for cognition. Aristotle argues that we need passion and desire to do anything, as without it we may have knowledge of the situation but won’t be motivated to act. For standard examples of behavior in animals, Aristotle uses the opposing pairs of pursuing, seeking after, and avoiding, fleeing from. He contrasts choice and decision with passion, as animals have passion and desire, but only humans can deliberate, making rational choices. We alone as humanity have the capacity to understand the world, and not merely react to it. In his Parts of Animals, Aristotle says that the throbbing of the heart is peculiar to humanity, as only we have hopes and expectations of the future. This is odd, as Aristotle examined animals in great detail, and could have easily listened to the heartbeat of any living goat and heard differently.

In Wonderland, Alice is amazed by the White Rabbit, who runs passionately like an animal down the rabbit-hole, but also absurdly has a watch and waistcoat, and cries that he is late, which directly contradicts Aristotle and his argument that we alone are the rational animal. For Alice, this is eventually evidence that she has fallen asleep and is dreaming. She rushes, as we and Carroll originally said, “down the rabbit-hole”, without thinking, giving in to her lower passion and not putting it in check with her higher human mind, a human like a rabbit, just as she follows a rabbit who is like a human. Aristotle denied that animals other than human have rationality and beliefs. For Aristotle, if animals have memory, or foresight, these must not involve reason, nor belief. Aristotle argued that imagination (phantasia) preserves the sensible for animals, including humans, as internal representation. For animals, imagination functions as rudimentary thinking, which humans do with reason, making us the only rational animal. Thus, animals can remember objects not present to perception, as well as envision possible courses of action, via imagination. However, animals cannot engage in abstract reason as we do, thinking about general and universal groups of things, and forming beliefs beyond mere immediate reactions.

It is odd, but true that Aristotle distinguishes us from all other animals, but at the same time was more invested in investigating animals and our similarities to them than almost any other thinker of the ancient world. There were thinkers in ancient India, Greece and China who chose to live among the animals and leave human society, as they thought it was corrupt and corrupting, but Aristotle observed the animal world and based his influential texts on what parts we share entirely with them and which part we do not. In his Parts of Animals (645a5-36), he wrote, “We therefore must not recoil childishly from the examination of the baser animals: for in all strata of nature there is something marvelous… so too should we embark on the study of every kind of animal without disdain, since in each of them there is something natural and beautiful.” After leaving Plato’s Academy, and before returning to Athens to teach at the Lyceum and write his most influential work, Aristotle studied animal life on the island of Lesbos for about five years, famous for the Lesbian poet Sappho, who wrote love poems to other women, and from whom we get our modern word lesbian.

Sappho wrote that each person has something, often different things, that make them happy. In one of her most famous poems, she wrote, “Some say an army of horsemen, others say foot-soldiers, still others, a fleet, is the fairest thing on the dark earth. I say it is whatever one loves… I would rather see her lovely step and the radiant sparkle of her face than all the war-chariots in Lydia and soldiers battling in shiny bronze.” For Aristotle, this subjective relativism is not good enough, much as he thought about the philosophy of Heraclitus. Aristotle believed that humans have a purpose which is the fulfillment of human nature, the aim of the good life. While many goals in life merely lead to further additional goals, such as the goal of making money leading to the goal of pleasure or security, Aristotle that there must be a final goal, an end in itself. What is this final goal, which should be universal, common to all of humanity, and particularly exclusive to humanity?

Humanity alone has reason and belief, unlike all other animals. However, it is not simply reasoning, but thriving, and thriving in understanding and reasoning about how to thrive that is the ultimate and exclusive fulfillment of humanity and our superior minds and lives for Aristotle. He argues, in the opening of Book 1 of the Nicomachean Ethics, that if we are to understand human nature and the form of the good life, we must find something which is pursued for its own sake and universally valued. It is reason, the work of philosophy and science, which is the realization of human purpose, the fulfillment of human nature, and for the specific end of human self-conscious thriving.

The word Aristotle uses is eudaimonia, which has sometimes been translated as happiness, but is more accurately translated as thriving, but thriving is not simply the same thing as happiness, as Aristotle knows. He argues that a life devoted to pleasure is no better for humans than it is for grazing cattle, not fulfilling our highest faculty of intellectual virtue. While thriving is what any flourishing animal or plant life does, we should and do thrive best when we do so intentionally and rationally, with correct beliefs and reasons as to how and why we thrive. Thus, we achieve from our topmost faculties downward intellectual virtue, moral virtue, and nutritional virtue, in tune with Plato’s three-part soul, Republic, and Timaeus.

There is a strange paradox here, one which crops up in other forms in the works of later famous European philosophers who focus on reason, such as Descartes and Kant. Both of these central European thinkers argued in the first words of their central texts, over two-thousand years after Aristotle, that most if not all people have reason, but very few people use reason, and very, very few use reason well. Aristotle argues in his work on politics that most of humanity, including Sappho, women, slaves, Germanic tribes (Kant’s ancient ancestors), and most others, other than the aristocrats who have the time and money to study for learning’s own sake, are not capable of reason and should be assigned other tasks that serve those who are free to reason, entirely in tune with Plato’s Republic. Thus, we are left to conclude that Aristotle holds we should strive to fulfill our true purpose, but that the vast majority of humanity are incapable of this, which begs the question: Is reasoning our true, exclusive purpose, if most of us can’t?

Let us examine Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, and his argument as it unfolds. Aristotle opens his Nicomachean Ethics with the statement that every sort of action and practice seems to seek some good, an end of some sort. Aristotle, like many of the ancient world, had a teleological view of the cosmos, such that the cosmos is godlike and intelligent beyond ourselves, and such that we have purposes when we act, and the universe has purposes as it acts. Ultimately, like the Stoics, Aristotle argues that we should seek to do what is natural to us, such that the ends of our own actions are the same ends that our nature and the cosmos has for us. If our ends line up with the ends that are natural to us, this allows us to thrive in tune with our true purposes and ends.

We should mention, given this opening statement, that we will be contrasting Aristotle’s position with Kant, who says we should always follow rules we have reasoned to be universal, and with Mill, who argues that we should aim for the best consequences of our actions. While Aristotle agrees with Kant that we should reason as to the universals of things, and Aristotle agrees with Mill that we should aim for best ends, Aristotle ultimately does not side with Kant that there are rules that can be followed regardless of what consequences there are, nor does he side with Mill that we should aim for the best possible ends regardless of what we find to be universal. Rather, Aristotle will argue that we should pursue ends, like Mill rather than Kant, but also that the ends we should seek are natural and universal to us, and not simply whatever ends we find turn out best, like Kant rather than Mill.

Aristotle makes the distinction between actions with ends that are ends in themselves, and actions that have ends that are products for further ends that are greater than the initial actions and ends. He uses the example of bridal-making, fashioning leather into tools for riding horses, which is done for the purpose of mastering horses. This, however, is not the final purpose, as mastering horses is, Aristotle argues, for the purpose of warfare. Thus, he argues that warfare, conducted by generals, is more valuable and sought-after than bridal-making, which is only valuable insofar as it serves the greater purpose of warfare (I.1).

Aristotle seems to assume that there are singular ends to things, but even if bridal-making serves mastering horses, why should mastering horses ultimately serve warfare, rather than travel, or commerce, or recreation? Do things need to have singular ends, in themselves or in other ends? Wittgenstein would say no, and there could be many overlapping or even exclusive ends for particular things, such as mastering horses for both warfare and recreation, but Aristotle argues as if it is clear that we do things for one particular end or another, as Aristotle assumes a rational, teleological universe that has a proper, singular end for each thing if we properly understand it. Aristotle argues that if we did everything for another, further end, such as bridal-making for warfare, and then warfare for something else, and then that something else for something else, it would result in an infinite regress, as an endless train that doesn’t end ultimately in anything, which he says would, “make our desire empty and vain”. (1.2) Aristotle, like other Greeks, was not particularly into the idea of endless infinity, contrasting it with the finite, rational, and properly formed.

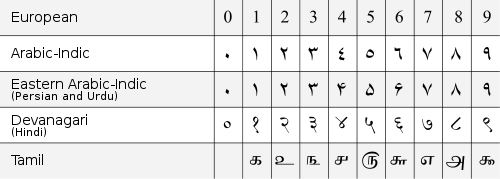

Infinity which goes onward and beyond our understandings and desires seemed monstrous to him, seen here in this text and elsewhere in his works. Muslims, who read their share of Aristotle, used Indian numbers, our own Indo-Arabic numerals we use today, rather than Greek or Roman numerals to create algebra, and they also employed Indian mathematical series that continue onward to infinity, which were absent from Greek mathematics.

For whatever reason, Indian mathematicians did not seem to fear infinite series the ways the Greeks and Aristotle did. While we use the Greek symbol and letter Pi for the ratio of a circle to its diameter, the Greeks tried to understand it as a whole ratio, something about 22/7, and would not like the idea of 3.1415… onward without any repetition or pattern, which would be irrational, and in so perfect a figure as a simple circle! Here, in his ethics, Aristotle similarly argues that the cosmos is rational in ways we can understand, that the ends end somewhere definite, and that an infinite regress would frustrate our desire to frame and understand things completely. Aristotle says that we must seek the most sovereign, godlike end for each action, the ultimate, terminating telos and purpose, the “top-most”.

Aristotle says that there are no things that are simply and always good, no matter the situation, as people have perished from having wealth, and also from courage, so wealth and courage, which Aristotle goes on to portray as primary goods we often seek, do not always bring about good ends. Aristotle likes categories, and distinct categories, and Kant will later say that lies are always bad, categorically, but Aristotle does not argue that wealth or courage, often good, are categorically and universally good. Thus, wealth and courage serve some other end, which for Aristotle would be the good itself we are seeking. For Aristotle, there can indeed be too much of a good thing, and he warns us that we might be tempted to say that good things are always good to over-simplify our understandings, beyond what is in fact the case and is most reasonable.

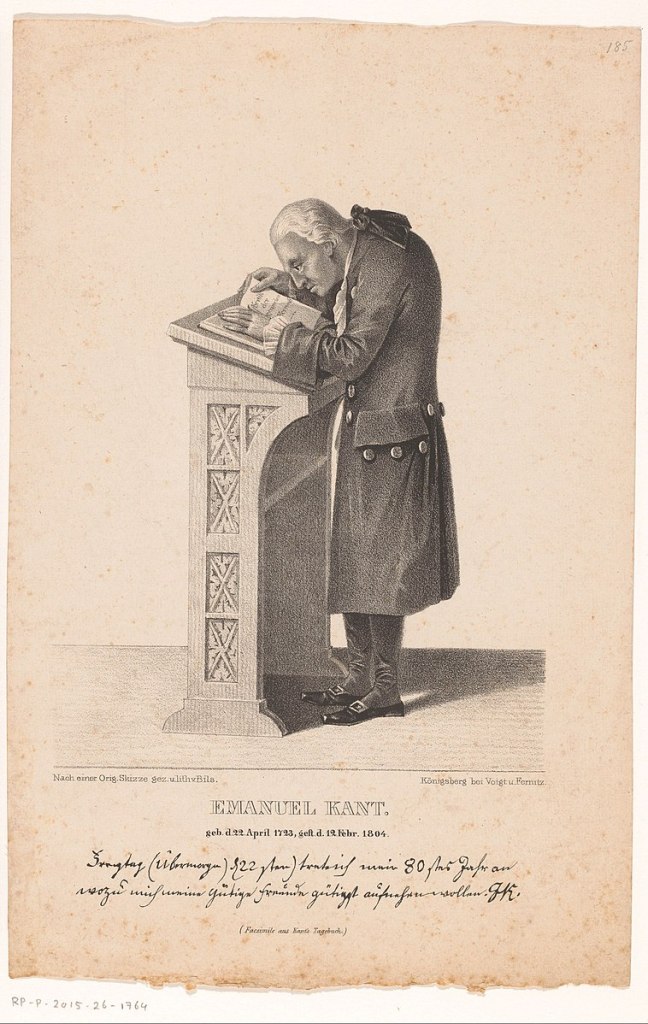

Rather, Aristotle argues that we must acquire expertise, habits and informed knowledge that allows us to judge when things are good, and when things that are sometimes good are bad for our sought-after ends. This is one of the major differences between Aristotle, Kant and Mill. While Kant says that we should always follow good rules, and Mill says we should always aim at the best possible ends, Aristotle argues that we should acquire virtue, a well-experienced character that can judge when rules and ends are situationally appropriate. While Kant and Mill could agree, to a degree, Aristotle ultimately does not say we can judge once and for all which rules or ends are good, but rather we should acquire the habits and character that allow us to continue making the best judgements we can, situation by situation. This is not far from Mill, but Mill emphasizes the ends, rather than acquiring character. To illustrate, here to the left is an image of Kant lecturing at the lectern with bad posture, a sign of bad habits.

Aristotle thus says the young are too young to become experts and know what is right, and they are ruled by their emotions, not yet having acquired knowledge and character by way of reasonable actions over long periods of practice. It is only by judging things situation by situation that we each have the opportunity to grow in virtue and character, that we gain the ability to judge well by having judged many things, rightly and wrongly, before. There are adults who are also immature, which is why it is not a matter of how much time has passed, but if there has been time passed, and that time has been well spent in gathering good, valuable experience.

What is the top-most, sovereign, godlike good and end, which is good in itself, unlike mere wealth or courage? Aristotle says that most people would say it is happiness, and assume that living well and doing well are the same thing as happiness, but the relationship between happiness and thriving is unclear. Epicurus argued, as we will examine after Aristotle, that happiness is the ultimate aim, but that enduring happiness is better and truer than fleeting happiness that does not last. Aristotle ultimately argues that happiness is secondary to thriving, to living and doing well, which is the ultimate end that all living beings strive for, whether or not they realize this consciously and conceptually with reason.

Confusingly, eudaimonia, the Greek word Aristotle and others use for thriving, is sometimes translated as happiness, but as many an intro to Aristotle’s ethics has clearly stated, it should be consistently translated as thriving, as Aristotle explicitly argues that pleasure is secondary to thriving as our fulfilling natural purpose, even if it causes pain and unhappiness. For Aristotle, pleasure and happiness often follow thriving and doing well, but they are not the ultimate aim for humanity. Animals and children seek pleasure and happiness, but they are not rational and experienced enough to see that thriving is what is lasting and ultimate. Epicurus can be understood in line with this overall position. Schopenhauer, the much later German philosopher and follower of Kant, pessimistically argued that happiness is fleeting, and life is rather a pendulum between boredom and pain.

Aristotle says there are three kinds of lives for human individuals: 1) the pleasurable life, 2) the political life, and 3) the reflective life. (1.5) Notice the fit with the three levels of Plato’s Cave and form of the city and the soul, all found in the Republic, which also fits quite well with Heraclitus’ three sorts of humanity, the masses, experts, and those who continue to push onward, but without any definite mouth to the cave of subjectivity and perspective. Aristotle says that the most slavish sort of people, mastered by their desires rather than mastering their desires with spirit and reason, are living a life devoted to pleasure which is a life better suited to grazing cattle. Those who seek to live a better life mostly seek the second, political life, devoted to honor and action. Aristotle says he suspects that more seek a political than a reflective life because they seek something that would belong to themselves rather than the contemplation of the universal beyond each individual, which does not belong to anyone. Excellence is greater than pleasure for those who seek a life above mere cattle-like grazing, but most who seek excellence seek it in the form that they can keep to themselves. Clearly there is something greater and more universal than living a life aimed at individual excellence.

Excellence is of greater value than pleasure, and those who seek excellence for themselves seek the approval of those who seek more than simply their own pleasure, of those who also seek excellence, but Aristotle says that those who seek honor and achievement can also be asleep, as well as unhappy, as they are seeking approval for their own mortal selves and not something completely stable, universal and eternal, such as the forms and ways of the cosmos. Note the similarity with the Buddhist Monkey Mind, and those who Buddhism says simply smile on all that is, no matter what changes or what one possesses for oneself. The great artist, athlete, poet or philosopher who seeks glory and honor is still living a life like that of a money-maker, one which can bring unhappiness with the twists and turnings of fate. While Aristotle does say that those who pursue philosophy, contemplation and reflection should have enough money and comfort that they do not need to seek these things, it is because a life spent seeking these necessary but distracting things is not proper for pushing on from individual pursuits to universal ones.

Aristotle values friendship, and we will cover his views on friendship and its importance for the social animal which is humanity found towards the end of the Nicomachean Ethics, but Aristotle argues that truth is to be pursued over all other things, which is to pursue substance above quality, (1.6) two of Aristotle’s primary logical categories. To be consistent, this would mean that truth leads more to thriving than honor for Aristotle, and the good of honor and achievement is only relative to the individual, while truth and substance itself is universal and allows any and all individuals to thrive more than what an individual can possess relative to themselves, and to particular times and places. Truth, beyond relative perspective, outside of the mouth of Plato’s Cave, is good in itself, as is the thriving it provides, and thus it is preferable and more valuable to everyone than things merely useful to this or that person here or there, now or then, even if most individuals would fail to recognize this while seeking a life of pleasure or a life of particular honor.

The intellectual life is not free from any problem or partiality, however, as a doctor who knows medicine and the ways of nature can seek to know medicine for this or that purpose, such as honor or wealth, rather than simply knowing the way all things are. While knowing medicine means knowing physics for Aristotle, and thus knowing the ways of the cosmos, the doctor can pursue medicine and healing for their own purposes, and can neglect reflecting on truth itself just as a weaver or carpenter can ignore reflecting on truth itself, even if truth and substance itself allows for all weaving and carpentry. The Cosmos, as the great one Substance itself, thrives, and in thriving is each and every one of us, whether or not we each thrive, so it is only when turning to contemplation of the whole that the intellectual, reflective life reaches its peak, not in a career that is very useful to all, like medicine, but in philosophy and cosmology.

Thriving is shared by plants and animals, but it is particular to humanity to be capable of understanding and reasoning with universals, and so understanding thriving as shared by plants, animals and humanity universally, something that a plant, animal or most of humanity are either not capable of doing or do not do. We reason, and so we can reason that all things thrive. True excellence is not pursued as this or that thing, but excellence of everything. Aristotle famously says, “One swallow does not make a spring, and neither does a single day make us happy and thrive.” (1.7) If we seek particular things, whether or not we gain them, then we do not go on to discover more and more things beyond what we desire, keeping us in a narrow frame. Aristotle says that the carpenter and the geometer, the mathematician who practices geometry, both seek right angles and use them, but the carpenter seeks them only insofar as they contribute to the particular product of labor, while the geometer seeks truth with their gaze, and what is true of right angles no matter what use we put this knowledge to before or afterwards.

We seek some things because of other things, and we seek some things because they are good for the body, which is something sought in-itself as our own individual thriving, but it is only that which we seek for the mind, the master of the body and our higher, essential self, that is best and most sought in-itself. (1.8) This is because the mind can grasp the whole with reason, which the body cannot do with hands, and the mind can find pleasure and fulfillment in the thriving of each and every thing along with the whole, something that seeking this or that pleasure or good for this or that body cannot. Such happiness and thriving does not need particular things, like pieces of jewelry pinned on here or there, but has pleasure from within, independent of individual mind, body or relative state. Oddly enough, Diogenes Laertius, the biographer of the philosophers who wrote years after Aristotle was long gone, said that Aristotle used to wear a lot of rings, which we don’t find in any other source. Aristotle argues that children and animals, such as the horse and ox, cannot be truly happy, as they only know this or that fleeting happiness, unable to rest in the happiness and thriving of the whole through reason. (1.9)

Aristotle says that the finest shines through, and someone who bears repeated misfortunes calmly, not because they do not feel or understand them but because they have a greater source of happiness and thriving than the particular fortunes and misfortunes that pass with time, are the truly great in soul. (1.10) This sort of person is truly blessed, and will never become truly miserable according to Aristotle. Just as a general uses an army as best as one can, and a shoemaker makes a shoe as best as one can, the one with true happiness and fulfillment through reason and its activity is as happy and fulfilled as one can be in all of life and the pursuits of the mind and body. Aristotle says that even if they were to meet the same misfortunes as Priam, the King of Troy who suffered such losses during the events of Homer’s Iliad after his son kidnapped Helen, such an individual would not be absolutely miserable.

Even if one were to lose their family, their kingdom, and all of their wealth, like Priam of Troy, such an individual would have reason to see beyond particular things, no matter how desirable, and this would bring the greatest degree of self-control (1.13), which only comes about by way of reason controlling spirit, controlling desire, as we found in Plato’s Republic. Aristotle was an influence on Stoicism, which we will cover after Aristotle and Epicurus, and the Stoics place the highest value, as does Aristotle, on self-control via reason and logic. The non-rational parts of ourselves can be persuaded by reason, as the lower classes can be ruled by the philosopher, even if they cannot do so for themselves otherwise. The rational, those who live the life of reflection, are themselves obedient to reason itself, which Aristotle believes rules the Cosmos in common. It is such a character which can understand and practice the many virtues Aristotle now proceeds to detail in Book II.

Aristotle says that excellence of character results from habituation, which is why the word is very close to the word for character (ethos, with different accents on each e). (2.1) A stone which by nature moves downward cannot be habituated into moving upwards, even if it is thrown upwards ten thousand times, and fire will not move downwards. Excellences develop in us neither by nature nor contrary to nature, but because we are naturally able to receive them and are brought to completion by habituation. As Aristotle says, “We become just by doing just things, moderate by doing moderate things, and courageous by doing courageous things.” We acquire great character, a plurality of excellences, by practicing behaving in excellent ways, becoming just by doing just actions, and tempering our feelings to feel as the excellent do. This is begun by imitating good parents and guardians, but ultimately individuals are left more and more to themselves to choose their behavior on their own.

Just as there can be too much of a good thing in particular situations, in some situations a good thing is a bad thing. At the Mad Tea Party of Wonderland, the March Hare tries to fix the Mad Hatter’s watch by spreading butter on it, and when this only makes the situation worse, the March Hare says, “but it was the best butter!” The best of the best is still bad when it does not apply, or rather does apply when you spread it on the watch, but doesn’t do any good, as if spreading butter on a watch, like a biscuit, would be beneficial if only the quality of butter is best. Similarly, individuals are varied, each different with different abilities and tolerances, and what is good for one individual in a particular situation will not be good for another individual in the same situation. In Wonderland, after running all the other animals, birds and Alice around in a circle, the Dodo awards everyone prizes equally for participating, as if this particularly awards or promotes anyone over anyone, and the candies handed out are too big for the smaller animals, who choke on them, and barely anything to the larger animals, who swallow them without tasting anything. This is why each individual needs experience, and a variety of experiences, an “intermediate diet of challenges”, as Broadie puts it in her introduction to the Nicomachean Ethics. (p. 20).

At first, human individuals are neither wise nor disciplined. Aristotle says they must be taught wisdom and discipline by others who are already rational and moral, and then through practice develop what they receive from others to become rational and moral themselves. Aristotle argues that we are not only the rational animal, we are also a social animal, though not the only social animal, as Aristotle says bees are admirably social thriving in the hive together. Unsurprising to anyone, if we hang around the foolish and cowardly, as Alice does at the Mad Tea Party (“The worst tea party I’ve ever been to,” according to Alice), we become foolish and cowardly ourselves, but if we hang around the best people, courageous in spirit and wise in mind, then we have the opportunity to learn to imitate them, even as we must adjust to what is appropriate to ourselves as an individual, which may not be the same for another individual, no matter how good, courageous or wise they are overall.

Aristotle says that we come to be great by doing great things, and that the virtues of properly habituated, conditioned character, tempered by experience, can be destroyed by deficiency or excess, too little or too much in this or that situation, as we can observe in the course of life. (2.2) Aristotle, like an ancient Greek, uses the example of exercise, saying that too much training can destroy strength, just as too little training can do. He uses the example of eating and drinking too much or too little destroying health as well, complimenting the example of exercise and spirit with an example of sustenance and nutrition, the heart and the stomach. Confucius gives us a good example of intellectual balance, saying in the Analects that too much study without putting things into practice can be bad, but so can studying too little and practicing too much without it as well. Aristotle says that this is like all of the virtues, which are not simply three, but do find their way into the three types Aristotle articulates in accord with Plato.

So too it is, then, with moderation, courage, and the other virtues. For someone who runs away from everything, out of fear, and withstands nothing at all and advances in the face of just anything becomes rash; and similarly too, someone who takes advantage of every pleasure offered and holds back from none becomes self-indulgent, while someone who runs away from every pleasure, as boors do, is insensate, as it were. Moderation, then, and courage are destroyed by excess and deficiency, and preserved by what is intermediate between them. But not only are the excellences virtues brought about, increased, and destroyed as a result of the same things, and by the same things, but it is in the same things that we shall find them activated too… From holding back from pleasures we become moderate, and also when we have become moderate we are most capable of holding back from them; and similarly, too, with courage – from being habituated to scorn frightening things and withstand them we become courageous people, and having become courageous we shall be best able to withstand frightening things.” (2.2)

In acquiring intellectual, moral and nutritional virtue we find that a balance between extremes is best, what Aristotle calls the Doctrine of the Mean. ‘Mean’ here is the middle, not ‘mean’ as rude or aggressive. In all things, we must chart a middle course between excess and deficiency, too much or too little, the two opposite extremes. We should not take the intermediate as exactly halfway, but what is relative to the individual in the individual case, just as, Aristotle says, a physical trainer does not prescribe the same halfway amount of effort for one who can do less or one who can do much more in running and wrestling. (2.6). Aristotle writes, “It is possible on occasion to be affected by fear, boldness, appetite, anger, pity, pleasure and distress in general both too much and too little, and neither is good; but to be affected when one should, at the things one should, in relation to the people one should, for the reasons one should, and in the way one should, is both intermediate and best, which is what belongs to excellence.”

This is quite a bit like the children’s story Goldilocks and the Three Bears, one of the most popular folk tales in English from the 1800s. In the story, which you have likely heard before, Goldilocks, a golden-haired girl much like the golden mean between extremes, finds a cottage in the woods which unknown to her is the home of a Father Bear, Mother Bear, and Baby Bear. Goldilocks finds the porridge of the larger, Papa Bear to be too hot, the porridge of the Mama Bear to be too cold, and the porridge of the Baby Bear to be just right, and eats it all. She similarly finds the Baby Bear’s chair and bed to be just right, though she breaks the Baby Bear’s chair when she sits in it. The story may or may not have been intended as an illustration of Aristotle’s ethics, just like Alice in Wonderland, in 1800s England. The only problem and inconsistency is that Goldilocks breaks Baby Bear’s chair, and it is not the medium-sized Mama Bear, but the smallest Baby Bear, who is the balance between extremes. Perhaps there is more danger for Goldilocks in the two largest bears, Papa and Mama, and the smallest bear is the least dangerous, just as moderation between extremes for Aristotle is not a guarantee of success, but rather the best sort of situation over the range, and over time.

Aristotle argues that there are many virtues, each a mean between a vice of excess and a vice of deficiency. Courage is the mean between haste and cowardice. Temperance is the mean between being too sensitive and too insensitive. Nobility is the mean between vanity and lack of self worth. Sincerity is the mean between boastfulness and self-deprecation. Wittiness is the mean between being too silly or too somber. Modesty is the mean between being too bashful and too shameless. Just like Aristotle’s categories, some of these are interrelated, not categorically distinct, and Aristotle is only somewhat successful at distinguishing them from each other. Similar balancing acts of virtue are found in Maat of ancient Egypt, Heraclitus of ancient Greece, the Jains and Buddhists of ancient India, and Confucius and the Daoists of ancient China. It can also, oddly enough, be found in the “Goldilocks Zone” of modern astronomy, as for life to grow on a planet requires water, which requires that a planet be not too close to its sun, too hot, nor too far from its sun, too cold, but rather, as Goldilocks says repeatedly, “just right.”

Let us go through the virtues one at a time which Aristotle mentions, illustrating each with examples. Aristotle says that different emotions and passions correspond to each of the virtues, (2.7) and thus in each it is reason which is determining how much we should allow ourselves to act to the extent of our emotions as the rational animal. We are all familiar with emotions, motives and interests, and could always justify any behavior citing one of them, but this is a mistake that works all too often, as we should consider whether the act is done in the right amount, and in the right way, not whether it simply has the right motive. Rather, it is whether or not we have the right motive, and whether or not we allow ourselves to act with the right motive, to the right extent, in accord with the situation.

Courage (andreia, like the name Andrea, manliness in Greek) is the intermediate between fear and defiance, between timid and aggressive. Aristotle says it is for facing death, wounds, and the worst that can happen. With feelings of fear and boldness, courage is the intermediate state, such that those who are excessively fearless and bold is rash, and the one who is excessively fearful and deficiently bold is cowardly. Moderation (sophrosune, or soundness of mind in Greek) is a term that meant self-restraint, but later to more narrowly mean restraint in pleasures of the flesh, as Aristotle uses it. Note that moderation is a word interchangeable with the Mean itself, but we are using it as a particular type in translation of Aristotle. With feelings of pleasure, the intermediate state is moderation, the excessive state is self-indulgence, the deficient state is insensate. Courage and moderation are complimentary and opposed, as potential pain calls for courage and potential pain calls for moderation, a contrast between appetite (epithumia) and temper (thumos).

It seems that there is balance on both sides of the middle, such that courage is balance on the active side of the middle, and moderation is balance on the passive side of the middle, as different situations each call for a balanced, reasoned behavior, whether or not it is acting or refraining from acting, but each also calls for a balance on one side or another of what could be viewed as balance and the middle overall. Some situations call for action, and balanced action, neither acting too much or too little, is best, and varies by situation. Similarly, some situations call for restraint, and balanced restraint is best, and varies by situation. There is one overall continuum, but whether or not one finds oneself on either side, there is further reasoning and balancing to do, given the variance of situations, individuals, as well as groups of individuals, all over time.

Speaking of time, in Alice in Wonderland, it is the Caterpillar who serves as time itself, and the one who teaches Alice temperance, to “keep her temper”. The Mad Hatter tells Alice that time is a him, and that Alice has certainly already spoken with Time. Alice, more cautious than the rude Hatter, says perhaps she has, assuming she has not, but being moderate and nice about it. The Caterpillar frustrates Alice, as he speaks slowly, forces her to wait, and angers her when he tells her to keep her temper, but this pays off, as Alice is better with the creatures she encounters afterwards. He also gives her the two sides of the mushroom he is sitting on, which allow her to grow and shrink in size as she wants to do, which has been a problem for her in the situations up to the Caterpillar. She is often too large and too small, and too aggressive and timid with others, until she meets the Caterpillar.

Then, immediately afterwards, she encounters a pigeon who thinks that Alice is some kind of serpent because Alice eats eggs. The pigeon flips out, and says that she is so tired from having to do so much all the time, and Alice patiently listens and understands, providing a contrast between Alice, now more patient, and the impatient pigeon. Aristotle says that when we are at an extreme on a continuum, our view is narrow and we fail to see the differences between the intermediate and opposite positions, even though these are opposed to each other. As such, cowards see the courageous as rash, and the rash see the mild as cowardly. While the pigeon sees Alice as some kind of serpent, overly threatening to her, Alice does not get angry or push back against this, but patiently listens to the pigeon, and sympathizes, showing that she has learned from the Caterpillar and is “keeping her temper” with temperance.

All of Aristotle’s virtues are between the extremes of acting too much and too little, and so they all fit quite snuggly with this simple presentation, but Aristotle argues that the emotions are many and there is a virtue to each, making the situation more complicated. The next virtue he discusses is the giving and receiving of money, as if money has its own specific emotion. With giving and getting money the intermediate state is open-handedness, while the excessive and deficiency states are wastefulness and avariciousness.

In Zen Buddhism, there is a story told in different ways, such that sometimes a man, sometimes a woman, is stingy with money and never wants to spend anything, like Ebenezer Scrooge from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, or Scrooge McDuck, based on Ebenezer. A zen master goes to the stingy person, and asks them what it would mean if a hand is always closed like this, sticking out a fist. The miser says that the hand would be deformed. The master then holds out an open palm, and asks them what it would mean if a hand was always open, like this. The miser says that the hand would also, equally and oppositely, be deformed. The master nods in agreement, and walks away without a word.

Aristotle confusingly says that the Great of Soul (megalopsuchia) are properly balanced between extremes, and the Little in Soul (micropsuchia) are overly self-deprecating, undervaluing their self-worth, on the other extreme from the conceited, like Baby Bear being the smallest, but the happy medium for Goldilocks. His system thus makes much sense, but there are ways the terms overlap and give way to confusions, which Aristotle is trying to avoid by separating each element out and giving it proper definition. With regard to honor, the intermediate state is Greatness of Soul, while the excessive state is called conceitedness, the deficient is Littleness of Soul. This could be considered another sort of greed, but a greed for honor and position, similar to but different from greed for money.

Mildness is intermediateness in terms of anger, who does get angry when appropriate. With regard to anger, the intermediate is mild-tempered, and the extremes irascible and spiritlessness. Alice and the pigeon again serves as a good example, showing the overlap between these virtues, and that Aristotle does not keep them entirely distinct and mutually defined. In the end of Wonderland, at the Trial of Tarts, Alice gets fed up with the foolish trial, grows large and assertive, and declares them all to be a pack of cards. She is indeed correct, as she then wakes from her dream, showing that all of the characters were in fact dreams and ideas as she said. Her anger is appropriate, and fits the situation. This illustrates well the balance of balances mentioned earlier, as she stays patient with the pigeon, and keeps her head down in the garden of the Queen of Hearts, where her head is threatened, but when she finds herself in an absurd trial where anything could count as evidence of anything, she righteously stands up to the injustice of it all, and exits the absurd situation.

Aristotle says that with regard to telling the truth, the intermediate state is truthfulness, while the excessive and deficient are imposture and self-deprecation. The Buddha says that we do not always have to tell the truth, not that we should lie, but that we do not always have to say something, regardless if it is true. This seems to be what Aristotle has in mind when he speaks of imposture. If someone feels the need to tell everyone all sorts of things, even when it is not appropriate, they are being a bit of a “know-it-all”, and not reading the room. Wittiness (eutrapelia) is another interrelated intermediate between extremes. With regard to pleasure in play (joking), the intermediate is wittiness, the excessive state is buffoonery and the deficient is boorishness. Friendliness, another interrelated virtue, is the mean between being pleasing and displeasing others, between seeking always to please and being contentious and confrontational. With regard to friendship, the intermediate of friendly is between the excessive state is obsequious, or for one’s own benefit ingratiating, while the deficient is unpleasant, contentious, and morose.

With regard to shame, the intermediate is between the excessive, who feel shame at everything, while the deficient are shameless, feeling shame at nothing. With regard to righteous indignation, the intermediate is distressed at those who do well undeservedly, while the excessive is grudging, distressed at anyone doing well, and the deficient is malicious and pleased by problems. This seems like a very particular kind of anger and aggression, specific to the position of others, which is opposite Greatness of Soul, seeking honor and position for oneself. Greatness of Soul is moderation in what we think we deserve for ourselves, and righteous indignation is moderation in what we think others deserve for themselves. Aristotle again seems to offer the same framework for each virtue, but says that there is a plurality of virtues just as there is a plurality of emotions and motivations, each with its own habits to acquire and situations to encounter.

Aristotle says, of the virtues overall, (2.8) “There being, then, three kinds of dispositions, two of them bad states, i.e. the one relating to excess and the one relating to deficiency, and one excellence, the intermediate state, all three are in one way or another opposed to all; for the states at the extremes are contrary both to the intermediate state and to each other, and the intermediate to the ones at the extremes; for just as what is equal is larger when compared with the smaller and smaller when compared with the larger, so the intermediate dispositions are excessive when compared with the deficient ones and deficient when compared with the excessive ones, in the spheres both of affections and of actions. For the courageous appear rash in comparison with cowards, but cowardly in comparison with the rash; similarly the moderate, too, appear self-indulgent in comparison with the ‘insensate’, but ‘insensate’ in comparison with the self-indulgent, and the open-handed appear wasteful in comparison with the avaricious, but avaricious in comparison with the wasteful. This is why those at either extreme try to distance themselves from the one between them, associating him with the other extreme: the courageous person is called rash by the coward, cowardly by the rash person, and analogously in the other cases. This being the way these things are opposed to each other, there is most contrariety between those at the extremes – more than between them and the intermediate; for they stand further away from each other than they do from the intermediate, just as the large stands further away from the small and the small from the large than either of them from the equal.”

Like virtue, Aristotle believes that justice is itself a balancing act. Agreeing with Plato’s form of the soul found in the Republic, which holds that justice is the lower put in check by the higher, Aristotle emphasizes that this is achieved by moderation. Justice has two sides, distribution of rewards to those who do good, which Aristotle calls distributive justice, and punishment to those who do wrong, which Aristotle calls corrective justice. Distribution and correction, also known as “the carrot and the stick” in the British folk tradition, is used to direct society, planned rationally by the philosophers and implemented courageously by the police.

Conflicts of desire, like social conflicts in the city, result in imbalance, in excess and lack. Socrates argued in Plato’s Republic that no one would knowingly do evil, as they would see that it is not in their best interest, so a conflict in desires can lead to ignorance and a lack of courage or wisdom. For Aristotle, it is possible for a person to knowingly do evil when they are conflicted, as they can see what the wisest or courageous choice would be but are too overwhelmed by an excess of desire or honor to do what they know to be right. In these cases, when our desire for pleasure outweighs our wisdom, we can knowingly do the wrong thing. Socrates, like the Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming, would say that if a person does not do what is right, then they may say they know what is courageous or wise but they in fact do not know, cannot be said to see what is good, and are merely telling others what they expect they want to hear. Wang Yangming argues that if one says a painting is beautiful or a smell is bad, but one does not act as if the painting is beautiful or the smell is bad naturally, one does not actually know but is merely saying that one is good and the other is bad.